ID 929413

Los 19 | Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Schätzwert

€ 1 000 000 – 1 500 000

Tête d'homme (III)

daté et inscrit '4.12.64.III' (au revers)

huile sur toile

55 x 46 cm.

Peint à Mougins le 4 décembre 1964

dated and inscribed '4.12.64.III' (on the reverse)

oil on canvas

21 5/8 x 18 1/8 in.

Painted in Mougins on 4 December 1964

Provenance

Vente, Me Kohn, Divonne-les-Bains, 7 août 1987, lot 514.

Collection particulière, France (acquis au cours de cette vente).

Puis par descendance au propriétaire actuel.

Literature

H. Parmelin, Picasso, Notre Dame de Vie, Secrets d'alcôve d'un atelier, Paris, 1966, p. 173 (illustré en couleurs).

C. Zervos, Pablo Picasso, Œuvres de 1964, Paris, 1971, vol. 24, no. 297 (illustré, pl. 119).

C.-P. Warncke, Pablo Picasso, Les Œuvres de 1890 à 1936, Cologne, 2003, p. 621, no. 2 (illustré en couleurs, p. 620).

Special notice

Artist's Resale Right ("droit de Suite").

If the Artist's Resale Right Regulations 2006 apply to this lot, the buyer also agrees to pay us an amount equal to the resale royalty provided for in those Regulations, and we undertake to the buyer to pay such amount to the artist's collection agent.

Post lot text

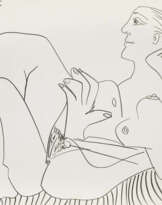

Le visage vigoureux et attentif de Tête d’homme (III) est un alter ego fascinant de Pablo Picasso, à la fois référence à l’artiste lui-même et témoignage captivant de la façon dont il explore le thème de la jeunesse. Tout au long de sa carrière, l’artiste andalou s’est représenté au travers d’une série de personnages pour renforcer les aspects allégoriques de son travail. Arlequin, faune, minotaure ou mousquetaire, les personnages auxquels s’associe Picasso sont sans aucun doute parmi les plus complexes et les plus riches de l’histoire de l’art moderne, et constituent un aspect fondamental de l’héritage de l’artiste.

Peint le 4 décembre 1964, Tête d’homme (III) fait partie d’une série de portraits d’homme que Pablo Picasso exécute dans son mas provençal de Notre-Dame-de Vie à Mougins. Il y vit aux côtés de sa dernière muse Jacqueline Roque qu’il a épousé en 1961. Picasso a alors 83 ans mais son énergie créatrice ne tarit pas pour autant.

Deux thèmes distincts récurrents dans tout l’œuvre de l’artiste sont clairement identifiables dans Tête d’homme (III): même si Picasso ne portait pas de barbe, cette représentation d’un homme plus jeune qu’il ne l’est au moment de l’exécution, est une manière pour lui de se rajeunir et d’incarner une certaine virilité. C’est également le portrait d’un matelot portant la traditionnelle marinière. Les premiers thèmes de la jeunesse et de la virilité sont explorés par Picasso tout au long des soixante-dix ans de sa carrière artistique. Lors de ses débuts à Paris, il fréquente de jeunes artistes avec qui il partage la découverte de ce nouvel univers, où l’ambition se heurte souvent à l’adversité. Une fois père, Picasso voit son énergie et sa curiosité redynamisées par ses enfants, qui insufflent à son travail un véritable renouveau. À partir de la fin des années 1940, Picasso utilise ses portraits du jeune homme, du fils, comme représentations de lui-même plus jeune. Pour évoquer sa virilité, Picasso s’est souvent mesuré au minotaure, au torero ou au mousquetaire. Enfin, à l’âge mûr, sa vision s’élargit à toute sa vie et au-delà, pour englober l’histoire des artistes qui l’ont précédés, un royaume où la présence de silhouettes juvéniles éveille la nostalgie.

N’ayant pas fait surface depuis son acquisition par les parents du propriétaire actuel en 1987, notre portrait incarne plusieurs de ces concepts. Picasso utilise diverses techniques visuelles pour représenter la jeunesse de son sujet. Contrairement à son portrait homonyme peint six jours plus tard, le 10 décembre 1964, vendu par Christie’s Paris en octobre 2017, le visage n’est pas de face, mais vu de trois-quarts. Il est également décrit au moyen de rayures, de points, de traits mais aussi d’aplats colorés. Les plans du nez et des pommettes sont ciselés en couleur pure contrastant intensément avec la blancheur du visage. Le fond angulaire de couleur rouge, vert et noir relève la note dramatique du portrait, qui respire la vie. L’effet général rappelle la manière des premiers dessins d’enfants et illustre la déclaration de l’artiste selon laquelle la technique en peinture est importante, «à condition d’en avoir tant… qu’elle cesse complètement d’exister» (cité in J. Richardson, Late Picasso, Paintings, sculpture, drawings, prints 1953-1972, cat. exp., Londres et Paris, 1988, p. 42).

Comme dans d’autres œuvres comparables de l’époque, les yeux formés de points noirs entourés d’une surface noire ou coloré qui domine le visage. Grand ouverts, les yeux soutiennent le regard du spectateur et le fixe avec une certaine défiance. Ces portraits de Picasso rappellent aussi ceux du Fayoum, à l’époque de l’Égypte romaine, où le défunt est représenté en prévision de son entrée dans l’au-delà. Les portraits de Picasso dégagent ce sentiment de transcendance du temps, mais plutôt qu’appréhender l’avenir, ils évoquent le passé, la tentative de l’artiste de capturer une vitalité perdue. Dans son portrait du 10 décembre 1964, l’homme porte une marinière traditionnelle, soulignant la nature autobiographique de ce tableau. En effet, Picasso en portait souvent, comme en attestent les photographies les plus célèbres de l’artiste, ayant une admiration pour ces personnages puissants que représentent les marins pour lui, probablement vus sur les quais d’Antibes ou de Cannes. Pour Picasso, le marin est l’archétype de la Méditerranée antique, un lien vers une période d’aventures épiques. Bien que le personnage de Tête d’homme (III) ne semble pas vêtu d’une marinière, ses traits méditerranéens très marqués font allusion aux grands héros de la mythologie grecque, laquelle influença Picasso tout au long de sa vie. Tel un Ulysse contemporain, ce jeune homme peint le 4 décembre 1964 jette sur le monde un regard dépourvu de crainte et plein d’espoir.

The vigorously depicted face in Tête d’homme (III) offers an intriguing alter ego portrait by Pablo Picasso, immediately identifiable as self-referential whilst also offering a captivating example of the artist’s exploration of the theme of youth. Throughout his career, the Andalusian artist portrayed himself through a series of surrogate personalities, employed as a means to reinforce the allegorical aspects of his work. As Harlequin, Faune, Minotaur or Musketeer, Picasso’s cast of self-associative characters is unquestionably the richest and most complex in the history of modern art, and constitutes one of the fundamental elements of the artist’s legacy.

Painted on 4th December 1964, Tête d’homme (III) is one of a series of male portraits Pablo Picasso produced at his Provençal farm Notre-Dame de-Vie near Mougins. He lived there with his last muse, Jacqueline Roque, whom he married in 1961. Picasso was then 83 years old but his creative drive remained as vigorous as ever.

Two distinct themes which recur throughout the artist’s work are clearly represented in Tête d’homme (III): notwithstanding its title referring to a man, the present work is clearly the depiction of a man clearly younger as Picasso is at the time of execution and as such a representation of youth. It is also a portrayal of a matelot or traditional sailor type. The first of these themes, that of youth, was one which Picasso would explore across the breadth of his seventy years of artistic activity. In his early years in Paris he close to fellow young artists and performers with whom he felt a shared sense of discovery whilst caught up in a world of ambition and hardship. As a father, Picasso’s energies and inquisitiveness were rekindled by the presence of his children, bringing to his work a sense of renewal through his observation of children’s innocence and directness. From the late 1940s, Picasso would use the portrayal of a young man, the son, as a junior edition of himself. Lastly, in his mature years, Picasso’s vision stretched back both across his own life and beyond to encompass the histories of previous artists, a realm where nostalgia and substitution resonated through the presence of youthful figures.

Having been discretely kept in the same private collection since its purchase in 1987, the present portrait serves to embody several of these concepts. Picasso’s depiction of his subject’s youthfulness is achieved through the use of specific visual devices. As opposed to its sister portrait painted six days later on 10th December 1964 – sold by Christie’s Paris in October 2017, the face is shown three-quarters turning towards the right and is not depicted straight on as in the later portrait. The face is defined by a shorthand of stripes, dots, coloured dashes but also coloured surface planes. The planes of the nose and cheekbones are chiseled in pure colour which contrast strongly against the whiteness of his face. The red, green and black angular background in Tête d’homme (III) enhances the overall drama of this portrait full of life. The overall effect thereby recalls the manner of a child’s first drawings, and illustrates the artists belief that technique in painting was important, “on condition that one has so much... that it completely ceases to exist” (quoted in J. Richardson, Late Picasso, Paintings, sculpture, drawings, prints 1953-1972, exh. cat., London and Paris, 1988, p. 42).

As in other comparable works from this period the face here is dominated by eyes formed of black dots surrounded by a sweep of yellow or red. Wide open, the eyes hold the viewer’s gaze with a certain defiance. Picasso’s portraits also recall those of Fayoum, from the Roman Egypt era, where the deceased’s likeness was painted in preparation for entering the afterlife. Picasso’s portraits share this notion of transcending time, but rather than apprehending the future they allude to the past, of the artist’s attempt to capture a lost vitality. In his portrait of the 10th December 1964, the sitter wears a traditional marinière or striped sailor’s shirt, adding an autobiographical dimension to his Tête d’homme. It is true that Picasso himself often wore a marinière, as testified by several of the most celebrated photographs of the artist. Picasso’s desire to associate himself with sailors reveals an admiration the artist felt for these brawny personalities, some of whom he no doubt encountered at the docks in Antibes or Cannes. To Picasso, the sailor represented an archetype of the Mediterranean’s past, bridging the gap to a time of epic adventures. Despite not wearing a marinière, Tête d’homme (III), there is no doubt that the man’s strong Mediterranean facial features recall that of the great heroes of Greek mythology, which inspired Picasso throughout his life. A modern day Ulysses, this young man painted on 4th December 1964 faces the world with fearlessness and expectation.

| Künstler: | Pablo Picasso (1881 - 1973) |

|---|---|

| Angewandte Technik: | Öl auf Leinwand |

| Kategorie des Auktionshauses: | Gemälde |

| Künstler: | Pablo Picasso (1881 - 1973) |

|---|---|

| Angewandte Technik: | Öl auf Leinwand |

| Kategorie des Auktionshauses: | Gemälde |

| Adresse der Versteigerung |

CHRISTIE'S 9 Avenue Matignon 75008 Paris Frankreich | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vorschau |

| ||||||||||||||

| Telefon | +33 (0)1 40 76 85 85 | ||||||||||||||

| Fax | +33 (0)1 40 76 85 86 | ||||||||||||||

| Nutzungsbedingungen | Nutzungsbedingungen | ||||||||||||||

| Versand |

Postdienst Kurierdienst Selbstabholung | ||||||||||||||

| Zahlungsarten |

Banküberweisung | ||||||||||||||

| Geschäftszeiten | Geschäftszeiten

|