English Silver Tableware - History, Fashion, and Styles

English Silver Tableware features a variety of styles. The fashion for dishware design has changed drastically over several centuries. The technology of processing precious metals in Great Britain has always been at a high level, but the finishing of English silverware depended on the popular trends in Europe. Wealthy patrons imported tableware from France and Germany, while London jewelers copied the styles that were in demand.

English Silver Tableware. Wine fridge with Earl of Scarsdale coat of arms, 1726-1727

English Silver Tableware. Wine fridge with Earl of Scarsdale coat of arms, 1726-1727

English silver tableware was considered a great treasure in British households as it could be melted down or pawned in difficult times. In the early Middle Ages, cups, jugs, and plates made of precious metals were a privilege of noble families - a detailed description of silverware can be found in the inventory of Lord Chancellor Walter de Merton, dated 1277. The demand for such items began to grow only in the 17th century due to the stabilization of the political situation, the growth of people's incomes, and the expansion of the middle class.

English Silver Tableware. Salt shaker with lid, 1584

English Silver Tableware. Salt shaker with lid, 1584

British Silver Tableware in the 17th-18th centuries

Antiquarian collecting of English silverware began only in the second half of the 19th century. Before that time, the artistic value of these items was not taken into account, and old pieces were considered material for melting down. Sometimes, the old decorations were removed from the objects and replaced with new ones to follow the fashion. A unique collection of English silver tableware is held in the Hermitage Museum, as the imperial family and Russian nobility cherished foreign luxury items.

English Silver Tableware. Jug, 1697-1698

English Silver Tableware. Jug, 1697-1698

In Great Britain during Oliver Cromwell's time, a huge number of family services were destroyed since both sides needed money to fund the civil war. The Puritans were against any excesses, so the silverware from this period is known for its functionality, durability, and extreme simplicity in design.

English Silver Tableware. Saucer, 1664-1665

English Silver Tableware. Saucer, 1664-1665

Baroque style was popular among the French and German nobility, but it only arrived in England with the restoration of Charles II to the throne in 1660. Massive, richly decorated items with intricate floral ornaments, bird figures, and cupids came into fashion. The attributes of royal dinners at that time were impressive in their size - the weight of Charles Kendler I's wine cooler reached 220 kg.

English Silver Tableware. Wine fridge, 1734-1735 гг.

English Silver Tableware. Wine fridge, 1734-1735 гг.

The restoration of the monarchy led to the emergence of a new nobility. The king rewarded his loyal followers, and the newly minted aristocracy actively bought luxury items. Soon, jewelers faced a shortage of silver, which led to the appearance of Queen Anne's style characterized by an abundance of smooth surfaces and modest engravings with heraldic motifs.

English Silver Tableware. Queen Anne style teapot with oven rack and table, 1724-1725

English Silver Tableware. Queen Anne style teapot with oven rack and table, 1724-1725

In the 1730s, simplicity became tiresome to the wealthy public, and decorative and fanciful motifs came into fashion. The discovery of American deposits partially resolved the material shortage issue, and English jewelers adopted the Rococo style from their French colleagues, incorporating an abundance of flowers, shells, and leafy scrolls. The British were more restrained in their works and avoided excessive extravagance. A characteristic feature of English silverware was the use of chinoiserie decoration with exotic scenes and botanical motifs.

English Silver Tableware. Chinese style teapot, 1757-1758

English Silver Tableware. Chinese style teapot, 1757-1758

After 1760, Neoclassicism replaced Rococo. The movement gained popularity due to archaeological excavations in Pompeii and the frequent trips of British nobility to the continent, where travelers were fascinated by ancient ruins. The architect and designer Robert Adam had a significant influence on the jewelry industry. Master craftsmen reproduced motifs from his drawings in their works, and finishing with columns, paters, and laurel wreaths became fashionable. Simple and affordable tableware with thin walls became popular among the middle class.

English Silver Tableware. Punch bowl, 1806

English Silver Tableware. Punch bowl, 1806

Victorian Silver Tableware

The decline of Neoclassicism occurred in the 1810s. The public grew tired of cold elegance, and there was an increased demand for massive and colorful table settings. The classical style remained relevant, but objects became heavier and more monumental. Decorations included ribbons, grapevines, and Egyptian symbolism. North and Central America supplied a vast amount of cheap silver, and jewelers' imagination knew no bounds.

English Silver Tableware. Gilded tea service items, 1813-1814

English Silver Tableware. Gilded tea service items, 1813-1814

Renowned master silversmiths:

- Peter Bateman.

- Paul Storr.

- Philip Rundell.

- Nathaniel Mills and his son.

- Edward Farrell.

With the development of technological progress in Great Britain, numerous factories emerged, producing inexpensive silver tableware, but mechanical rolling and stamping had a negative impact on the product's quality. Affluent individuals preferred to place individual orders at renowned workshops. Jewelers and silversmiths adapted to the clients' tastes and often precisely copied designs from previous centuries using reproductions.

English Silver Tableware. Coffee pot, 1851-1852

English Silver Tableware. Coffee pot, 1851-1852

As the Victorian era drew to a close, Art Nouveau arrived from the continent. The decor featured naturalistic motifs, and tableware was adorned with images of plants, animals, and humans. Restraint was no longer a concern - subtlety was sacrificed for opulence and extravagant beauty. Most manufactories were located in London, with Birmingham serving as a supplier of small table settings items: tableware, napkin rings, sugar tongs, toothpick boxes.

English Silver Tableware. Saucer, 1870

English Silver Tableware. Saucer, 1870

Technological advancements and the accelerating pace of life in the 20th century made silver an uneconomical material for making tableware. Fashionable restaurants opted for ceramic table settings, which required less labor-intensive cleaning and care. English silver tableware remains in demand among collectors worldwide. Among the lots of antique auctions, Very Important Lots, one can find a diverse array of table decorations from the shores of Albion.

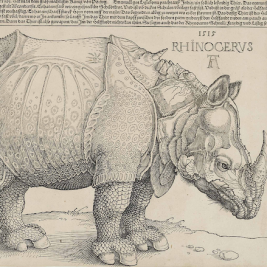

The engraving "Rhinoceros" by Albrecht Dürer - Europe's acquaintance with a curious beast

The engraving "Rhinoceros" by Albrecht Dürer - Europe's acquaintance with a curious beast  Silver - a noble metal

Silver - a noble metal  Application is a technique of decorative and applied art: essence, types, history

Application is a technique of decorative and applied art: essence, types, history  100th Auction at HERMANN HISTORICA from 7 to 16 May 2024

100th Auction at HERMANN HISTORICA from 7 to 16 May 2024  Photography is an art accessible to everyone

Photography is an art accessible to everyone  Modernism in painting - a different interpretation of reality

Modernism in painting - a different interpretation of reality  Expressionism - a shocking emotional movement in 20th-century art

Expressionism - a shocking emotional movement in 20th-century art  Chaim Soutine - an unsurpassed master of expression

Chaim Soutine - an unsurpassed master of expression  Animalism is a popular genre in painting from prehistoric times

Animalism is a popular genre in painting from prehistoric times  Art, antiques and ancient artefacts. 100th jubilee auction

Art, antiques and ancient artefacts. 100th jubilee auction