Rococo: Peasant Idylls of Court Painters

Rococo is an art style of the 18th century that embodies the elegance and carefree nature of secular life. Rococo originated in France and reached its peak during the reign of Louis XV and his brilliant favorite, Madame Pompadour, which is why it is often considered a French artistic movement. However, Rococo is not a localized phenomenon. Rocaille style tendencies found development in other countries as well, although they did not become the dominant artistic style for an extended period there. In France, mature Rococo became the hallmark of Louis XV's rule and even acquired a special name - the Louis XV style.

Rococo. François Boucher. Pastoral

Rococo. François Boucher. Pastoral

The name Rococo comes from the word rocaille (a diminutive form of "roc" - stone or rock), which in French means rocky debris. It is sometimes translated as rocky and shell. The reason for this is that the initial elements of this style appeared in the decoration of park grottoes, which were adorned with stones, rock fragments, and seashells. Against this backdrop, the characteristic decorative element of the Rococo style emerged - the rocaille scroll. The typical ornament is called rocaille, and this word formed the basis for the term "rocaille style."

Rococo. François Boucher. Madame de Pompadour, 1756

Rococo. François Boucher. Madame de Pompadour, 1756

The Genesis of the Rococo Style and the Characteristics of Rocaille Painting

Rococo is sometimes considered a continuation of the Baroque, but such a view is perhaps too simplified. Deriving the Rocaille aesthetic directly from the Baroque is impossible, partly because Baroque had relatively limited prevalence in France.

Rococo. François Boucher. Muse Clio

Rococo. François Boucher. Muse Clio

However, some external elements were indeed borrowed from the Baroque aesthetic: decorative intricacy, smooth lines, lush forms, emotionalism, and an interest in eroticism - in contrast to the cold rationalism of classicism.

Rococo. François Boucher. The Triumph of Venus, 1740

Rococo. François Boucher. The Triumph of Venus, 1740

At the same time, representatives of the new direction abandoned key Baroque principles:

- Scale, pomp, and monumentality were replaced by intimacy.

- Profound dramatic experiences gave way to light frivolity, softness, and sentimentality.

- The drama and contrasting palette were replaced by a bright pastel palette and smooth color transitions.

- The Baroque rejection of naturalism was replaced by an orientation towards the "natural joys of life," particularly rural attributes (it should be noted that the Rocaille painters' understanding of naturalism was quite specific - essentially, it was the aristocracy's idealized notion of pleasant leisure in nature).

- Realism in everyday scenes was replaced by depictions of gentle shepherdesses and refined peasants.

- If Baroque masters boldly portrayed deformity and pain, Rococo artists categorically rejected such themes and images.

- By foregoing emotionally strong themes, artists restricted their subjects to gallant narratives.

- Religious subjects practically disappeared (except for specific works and frescoes in churches).

- Emotionality became entirely different from that in the Baroque - it lacked tumult, affectation, or exaltation; it was more sentimental.

- Even Rococo eroticism is not the same as the joyful and juicy eroticism of the Baroque - it is playful, frivolous, and piquant.

Rococo. François Boucher. The Toilet of Venus, 1751

Rococo. François Boucher. The Toilet of Venus, 1751

Thus, new trends in art challenged not only classicism but also the Baroque on the artistic stage. Paradoxically, Rocaille aesthetics became not a development but a conceptual opposite of the Baroque.

Rococo. François Boucher. Pastoral

Rococo. François Boucher. Pastoral

To some extent, there was even a return to the refined elegance of the Mannerists. Jacques-Louis David even referred to Rococo as "erotic mannerism."

Rococo. François Boucher. Jupiter and Callisto, 1744

Rococo. François Boucher. Jupiter and Callisto, 1744

After us, let the flood come!

What led to the emergence of a new aesthetic? Wearied of the solemn opulence and grandeur of the so-called grand style of Louis XIV, the Sun King, society sought respite. The splendor of Versailles, reflecting the principles of absolutism, was not very comfortable. During the reign of Louis XV, the aristocracy declared a course towards hedonism. These sentiments were perfectly encapsulated in the famous phrase "after us, let the flood come," attributed to the king's favorite, Marquise de Pompadour.

Rococo. Maurice Quentin de La Tour. Portrait of the Marquise de Pompadour, 1748-1755

Rococo. Maurice Quentin de La Tour. Portrait of the Marquise de Pompadour, 1748-1755

As a result, high society life shifted to elegant drawing rooms and salons (rather than the vast halls of Versailles), and art embraced decorativeness, refinement, playful forms, fragility, poetic melancholy, and even a touch of coquetry.

Rococo. François Boucher. A beautiful cook

Rococo. François Boucher. A beautiful cook

In painting, pastoral balls and bucolic scenes dominated, against which gallant stories unfolded. Pastoral motifs became a hallmark of the era.

Rococo. François Boucher. Nest

Rococo. François Boucher. Nest

However, artists never depicted real shepherds. Their characters were more like nobles dressed up, oblivious to the hardships of life, sighing languidly against luxurious landscapes.

Rococo. François Boucher. A pastoral summer, 1749

Rococo. François Boucher. A pastoral summer, 1749

Mythological themes were often chosen, mostly of a provocative nature, such as the romance of Leda with a swan or the seduction of Callisto by Jupiter in the guise of Artemis.

Rococo. François Boucher. Leda and the Swan, 17850

Rococo. François Boucher. Leda and the Swan, 17850

Artists tirelessly celebrated the delights of elevated, yet sensuous love and delighted in painting nude figures.

Rococo. François Boucher. Hercules and Omphale, 1735

Rococo. François Boucher. Hercules and Omphale, 1735

Venus, nymphs, and other female mythological figures were abundant on canvases.

Rococo. François Boucher. Venus consoling Cupid, 1751

Rococo. François Boucher. Venus consoling Cupid, 1751

Many aristocratic ladies willingly posed nude for fashionable painters. It is believed, for instance, that François Boucher's "Reclining Girl" depicts a young lover of the king.

Rococo. François Boucher. Resting Girl, 1752»

Festivity and leisure were proclaimed as life's guiding principles. Joy and celebration pervade the atmosphere of the works, and laughter seems to emanate from many canvases.

Rococo. Jean-Honoré Fragonard. The Swing, 1767

Rococo. Jean-Honoré Fragonard. The Swing, 1767

Wit was not foreign to creators either, as it sparkled in the scenes of Fragonard. Domestic sentimental plots and frivolous everyday moments were also popular.

Rococo. François Boucher. Toilet, 1742

Rococo. François Boucher. Toilet, 1742

An original offshoot emerged - chinoiserie: an oriental branch reflecting Europeans' interest in exotic China.

Rococo. François Boucher. Chinese garden, 1742

Rococo. François Boucher. Chinese garden, 1742

The portrait genre saw intensive development. Interestingly, there was a fashion for depicting ladies in mythological settings, such as Marquise de Pompadour appearing as Diana the Huntress in Jean-Marc Nattier's painting.

Rococo. Jean-Marc Nattier. Madame de Pompadour as Diana the Huntress, 1746

Rococo. Jean-Marc Nattier. Madame de Pompadour as Diana the Huntress, 1746

Conversely, real beauties' features were discernible in mythological characters. For instance, in Charles-Joseph Natoire's Psyche, the features of the Duchess de Subiz are evident.

Rococo. Charles-Joseph Natoire. Psyche at her toilette, 1735

Rococo. Charles-Joseph Natoire. Psyche at her toilette, 1735

Rococo paintings often featured charming putti - winged infants, with many portraitists depicting children as little angels.

Rococo. François Boucher. Geniuses of the arts, 1761

Rococo. François Boucher. Geniuses of the arts, 1761

Rococo. Louis Caravaque. Portrait of the future Empress Elizabeth as an Olympic goddess, 1716-1720

Rococo. Louis Caravaque. Portrait of the future Empress Elizabeth as an Olympic goddess, 1716-1720

The characters in the paintings are always young and beautiful. Another characteristic feature of Rococo is the blooming blush, even adorning the faces of heroines resembling porcelain figurines (including Madame de Pompadour, who had a very delicate, frail nature). This juxtaposition of pale fragility and fiery blush is quite typical of the Rococo style.

Rococo. François Boucher. Sleeping shepherdess, 1760-1763

Rococo. François Boucher. Sleeping shepherdess, 1760-1763

Rococo. François Boucher. Madame de Pompadour at the toilet, 1758

Rococo. François Boucher. Madame de Pompadour at the toilet, 1758

The palette is also recognizable: light, subdued, even somewhat faded, yet rich with subtle shifts of delicate shades. Painters enthusiastically employed pink, blue, and lilac tones.

Rococo. François Boucher. Jupiter and Callisto, 1759

Rococo. François Boucher. Jupiter and Callisto, 1759

Outstanding Masters of Rococo

The precursor of this painting style is considered to be Antoine Watteau (full name Jean Antoine Watteau), who brilliantly depicted carefree festivities and amusements of the noble public.

Rococo. Antoine Watteau. Les Plaisirs du Bal, 1717

Rococo. Antoine Watteau. Les Plaisirs du Bal, 1717

The prominent figure was François Boucher, a portraitist, landscape master, and mythological subject artist. His shining moment came with Madame Pompadour.

Rococo. François Boucher. Leda and the swan, 1742

Rococo. François Boucher. Leda and the swan, 1742

Boucher was characterized by the perfection of drawing, tonal refinement, dynamic compositions, and boundless sensuality.

Rococo. François Boucher. Diana Bathing, 1742

Rococo. François Boucher. Diana Bathing, 1742

Another famous French artist, Nicolas Lancret, painted refined scenes against bucolic landscapes.

Rococo. Nicolas Lancret. Marie-Anne de Camargo (a famous dancer), 1730

Rococo. Nicolas Lancret. Marie-Anne de Camargo (a famous dancer), 1730

The works of Charles-Joseph Natoire and François Lemoyne were also popular with the aristocratic public.

Rococo. François Lemoyne. Venus and Adonis, 1729

A significant contribution to the history of art was made by the creator of historical portraiture, Jean-Marc Nattier. He portrayed monarchs and aristocrats. In 1717, Nattier painted portraits of Peter I and Catherine I, meeting the royal couple during their trip to Holland.

Rococo. Jean-Marc Nattier. Catherine I of Russia, 1717

The combination of humor and piquancy is characteristic of the playful paintings of Jean-Honoré Fragonard. While not gaining recognition as a landscape artist or master of battle scenes, he gained worldwide fame for his frivolous genre scenes.

Rococo. Jean-Honoré Fragonard. The Lock, 1776-1779

Rococo. Jean-Honoré Fragonard. The Lock, 1776-1779

Fragonard playfully and charmingly celebrated the small joys of love. His eroticism is mischievous and enchanting.

Rococo. Jean-Honoré Fragonard. The Stolen Kiss, 1787

Rococo. Jean-Honoré Fragonard. The Stolen Kiss, 1787

In Italy, rococo art also found its admirers. For example, Venetian artist Pietro Longhi worked in this style.

Rococo. Pietro Longhi. Visit to the library, 1741

Rococo. Pietro Longhi. Visit to the library, 1741

The works of Giovanni Battista Tiepolo combine baroque and rococo elements: sometimes he leans toward pathos and monumentality, but exquisite airiness prevails.

Rococo. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. Bellerophonte on Pegasus, 1747

Rococo. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. Bellerophonte on Pegasus, 1747

In England, pastel artist Francis Cotes gained fame, with his portraits pleasing the eye with delicate color combinations.

Rococo. Francis Cotes. Portrait of a lady, 1768

Rococo. Francis Cotes. Portrait of a lady, 1768

The works of another pastelist, Gustaf Lundberg from Sweden, who studied and worked in Paris for a long time, also gained recognition.

Rococo. Gustaf Lundberg. Marie-Anne de Bourbon-Condé, 1720

Rococo. Gustaf Lundberg. Marie-Anne de Bourbon-Condé, 1720

In Russia, rococo art arrived during the reign of Empress Elizaveta Petrovna and retained a certain influence during the reign of Catherine II, mainly in portraiture:

- Ivan Vishnyakov (Russian: Иван Вишняков) (1699–1761).

- Ivan Argunov (Russian: Иван Аргунов) (1729–1802).

- Aleksey Antropov (Russian: Алексей Антропов) (1716–1795).

- Fyodor Rokotov (Russian: Фёдор Рокотов) (1736–1808).

- Dmitry Levitzky (Russian: Дмитрий Левицкий) (1735–1822).

- As well as representatives of the so-called "rossica" (foreign artists who came to the empire), such as Louis Caravaque.

Rococo. Ivan Vishnyakov. Sarah Eleanore Fermor, 1749

Rococo. Ivan Vishnyakov. Sarah Eleanore Fermor, 1749

The Decline and Critique of Rococo Style

In the 1750s and 1760s, in France, critics began to criticize the frivolity of rococo art. After the death of Madame Pompadour, Boucher was accused of indecency.

Rococo. François Boucher. Pastoral scene

Rococo. François Boucher. Pastoral scene

With the reign of Louis XVI, a course of moderation and austerity was proclaimed. Rococo paintings were harshly criticized for their "strained," "affected," "dissolute," and "aimless" depiction of life by Enlightenment thinkers, including Voltaire.

Rococo. Antoine Watteau. Surprise, 1718

Rococo. Antoine Watteau. Surprise, 1718

But despite its lightness, rococo made a contribution to the development of art, showing that it could be optimistic, bright, and devoid of moralizing. Artists made art as secular as possible and drew attention to simple human pleasures (even from the perspective of the nobility). In this way, they, like the masters of the Renaissance, placed humanity at the center of art.

Rococo. Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Winning kiss, 1760

Rococo. Jean-Honoré Fragonard. Winning kiss, 1760

Today, rococo remains highly sought after at auctions. Examples of auction lots can be found on the VeryImportantLot website. Collectors are attracted to their investment value and exquisite decorative qualities; these paintings are magnificent interior decorations.

Meissen Porcelain: The History of the Manufactory

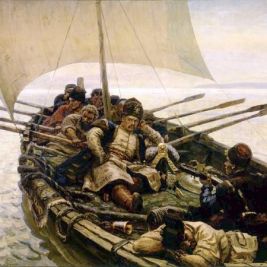

Meissen Porcelain: The History of the Manufactory  The painting "Stepan Razin" by Vasily Surikov is a tragic truth that triumphs over the epic image

The painting "Stepan Razin" by Vasily Surikov is a tragic truth that triumphs over the epic image  The most famous Dutch painters: 7 renowned masters from Van Eyck to Van Gogh

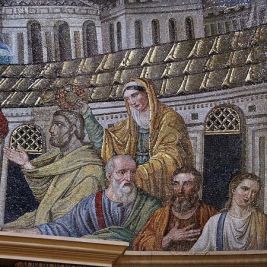

The most famous Dutch painters: 7 renowned masters from Van Eyck to Van Gogh  Mosaic - the art of creating a complete picture from many small individual pieces

Mosaic - the art of creating a complete picture from many small individual pieces  French Artists of the 18th Century

French Artists of the 18th Century  Top 10 Most Famous Architects - The Greatest Master Builders in Human History

Top 10 Most Famous Architects - The Greatest Master Builders in Human History  Vanitas is a genre of art that prompts the viewer to contemplate the inevitability of death

Vanitas is a genre of art that prompts the viewer to contemplate the inevitability of death  Marble Veil: Trompe-l'oeil Technique in Sculpture

Marble Veil: Trompe-l'oeil Technique in Sculpture  Classicism: strict ideals of high style - characteristics, history, iconic classicists

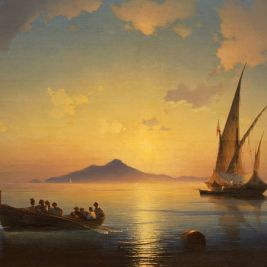

Classicism: strict ideals of high style - characteristics, history, iconic classicists  The painting "Bay of Naples" by Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky is an invitation to immerse yourself in the serene beauty of a southern evening

The painting "Bay of Naples" by Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky is an invitation to immerse yourself in the serene beauty of a southern evening