Doctors 18th century

Jan Bleuland was a Dutch physician, medical scientist, educator and writer.

Bleuland was an intellectually advanced man, a sought-after physician, and a rich lover of the arts. Jan Bleuland taught anatomy, physiology and obstetrics for 31 years and was professor and rector of Utrecht University. His talents as a physician and medical researcher were recognized not only by his patients and the scientific community, but also by the highest authorities.

During his lifetime, Jan Bleuland amassed a large collection of medical specimens of the human body, which he used for research. Part of this significant collection is still on display in the original wooden Bleulandkabinet in the Utrecht University Museum. The Bleulandkabinet contains an extensive collection of skeletons, embryos in alcohol and wax preparations of body parts. His pioneering preparations were acquired by Utrecht University by royal decree of King Willem I in 1815 and are still used as teaching material.

Aimé Bonpland, born Aimé Jacques Alexandre Goujaud, was a French and Argentine natural scientist, traveler, physician, and botanist.

Bonpland became famous for his participation in an expedition to the Americas. Together with the explorer Alexander von Humboldt, he traveled through much of the American territory, from Cuman to the United States, passing through Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Mexico, and Cuba, in addition to Venezuela. In all these places he did a great deal of botanical work, describing and collecting six thousand species of American plants, many of which were new. The scientist made them known in Europe after his return in 1804, publishing several scientific papers. Four years later, Bonpland was appointed botanist of the Empress's Garden.

After more years, he returned to Buenos Aires and continued numerous botanical, zoological, and medical studies in various regions of South America. Bonpland sent plants to the Museum of Natural History in Paris and maintained correspondence with its naturalists.

Edward Browne was a British physician, president of the College of Physicians, traveler, historian and writer.

Edward was the eldest son of the famous British scientist Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682), received a Bachelor of Medicine degree from Cambridge later and a Doctor of Medicine degree from Oxford, and became a member of the Royal Society. In addition to medicine, his subjects of study included botany, literature, and theology. He lived in London and traveled throughout Europe visiting museums, churches, and libraries (Italy, France, the Netherlands, and Germany). In 1673 he published an account of his travels in Eastern Europe, notable for its scrupulous accuracy.

Edward Browne also published two other works: a historical treatise and biographies of Themistocles and Sertorius. He was physician to King Charles II of England and left many manuscript notes on medicine. The chronicle of his journey through Thessaly is a unique and valuable source of information about the region in the second half of the 17th century. He was admitted to the College of Physicians in 1675 and served as its president from 1704 to 1708.

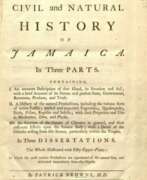

Patrick Browne was an Irish physician and historian, traveler, naturalist and botanist.

Patrick Browne studied medicine in Paris, graduated from the University of Reims, continued his studies in Leiden, and then worked as a doctor at St. Thomas' Hospital in London. Subsequently, he lived for many years in the Caribbean, in Antigua, Santa Cruz, Montserrat and Jamaica, where he practiced medicine. He devoted all his spare time to the study of the natural history of the island. In 1771, Brown returned to Mayo County.

In 1756, Brown published A Civil and Natural History of Jamaica, his most significant work in terms of Carl Linnaeus's botanical nomenclature, which included new names for 104 genera.

Pierre Chirac was a French physician and chief physician to Louis XV.

Chirac received his Doctor of Medicine degree from Montpellier in 1683, and three years later became professor of medicine. He was elected a member of the Academy of Sciences in 1716, became head of the Royal Garden of Medicinal Plants in 1718, and was appointed physician to Louis XV in 1731. In the 1690s Chirac selflessly and successfully engaged in the treatment of rampant at that time dysentery, yellow fever, smallpox.

Pierre Chirac was one of the leading physicians of his time; with an inquisitive mind, he was interested in several fields of medicine. In 1692, he wrote a significant treatise on cardiology.

Denis Dodart was a French botanist, naturalist and physician.

Dodart studied at the University of Paris, received a doctorate in medicine and was already in his youth known for his erudition, eloquence and open-mindedness. In 1673 he was elected to the French Academy of Sciences.

He is known for his early studies of plant respiration and growth. Dodart collaborated with the French engraver Nicolas Robert to illustrate his botanical works.

John Hill was a British botanist, pharmacologist and physician, geologist, writer and journalist.

Hill edited the monthly British Magazine for several years, and also wrote a daily society gossip column in The London Advertiser and Literary Gazette. His satirical, often on the edge of propriety articles were often the cause of scandals. Hill also wrote novels, plays, and scientific works on geology, medicine, philosophy, and botany.

In 1759, the first of the 26 volumes of his Plant System was published. This voluminous work contained descriptions of 26,000 different plants and 1,600 illustrations. For this long work, Hill received the Order of Vasa from the Swedish king and began calling himself Sir.

Martinus Houttuyn (Dutch: Maarten Houttuyn) was a Dutch botanist, zoologist and physician.

In addition to his medical practice, Houttuyn practiced science and published many scientific works on natural history, including minerals, fossils, botany and zoology. He was also a keen student of ferns, mosses and seed plants.

Carl Linnaeus was a Swedish naturalist, botanist and physician.

Carl Linnaeus created a unified system of classification of flora and fauna, in which he summarized and organized the knowledge of the entire previous period of development of biological science. He was the first to formulate the principles of definition of living beings of natural nature and created a unified system of their names, binary nomenclature. Linnaeus' book "The System of Nature", first published in 1735, is one of the most important books in the history of science and practically opened the classification of plants and animals.

Linnaeus was a professor at Uppsala University for many years, and he is also valued in Sweden as one of the creators of the literary Swedish language in its modern form. In addition to his work in botany and scientific classification, Linnaeus led many activities for the betterment of his native country. He was also involved in the establishment of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

Martin Lister was a British naturalist and physician.

It could be argued that Lister founded two fields of natural history: arachnology (the study of spiders) and conchology (the study of the shells of organisms). He wrote more than 60 articles in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, published several volumes on natural history, speculated on the mysterious nature of fossils, and was successful as a physician.

Lister employed his artist daughters to illustrate his books on insects and molluscs - the names of Susanna and Anne appear on the title pages of the volumes. The Lister family published Historiæ Conchyliorum between 1685 and 1692.

Paolo Mascagni was an Italian physician and anatomist.

He graduated from the University of Siena in philosophy and medicine, becoming a professor of anatomy there and focusing on the human lymphatic system. Mascagni outlined his discoveries in a book with detailed illustrations of each part of the lymphatic system he identified. In studying the lymphatic system, Mascagni refined the technique: he injected mercury as a contrast agent into the peripheral lymphatic networks of a human cadaver and, by tracing the movement of mercury into other parts of the system, was able to create detailed diagrams and models. By studying physiology and pathology, he was able to emphasize the importance of the lymphatic system in combating diseases of the human body, which helped to develop new treatments.

Mascagni helped to enrich the collection of wax anatomical figures in the Florence Museum, and commissioned the sculptor Clemente Susini to make a full-scale model of the lymphatic system in wax, which can still be seen in the Museum of Human Anatomy at the University of Bologna. Mascagni created the Anatomia universale ("General Anatomy"), a huge unbound book of 44 copper sheets with anatomical illustrations. The scientist pursued the task of collecting in one book the entire body of knowledge about the anatomy of the human body. Each plate is made in such a way that drawings relating to one plane of dissection can be placed together and show the whole body in life-size.

In addition to anatomy and medicine, Mascagni was interested in mineralogy, botany, chemistry, and agriculture.

Johann Friedrich Meckel the Younger was a German anatomist, biologist and professor of anatomy.

Meckel came from a family of physicians; his grandfather and father were physicians and anatomists and had their own anatomical museum at home. Meckel studied medicine at the universities of Halle and Göttingen, writing his doctoral dissertation on congenital anomalies of the heart. As a pathologist, he specialized in the study of congenital malformations and aspects of lung and blood vessel development. He also described Meckel's diverticulum, which he discovered during a pathologic examination, and became the founder of the science of teratology.

After Napoleon's occupation, the University of Halle reopened in May 1808, and Meckel was appointed professor of surgery, normal and pathological anatomy, and obstetrics. He taught throughout his life, continued to conduct research in pathology, and collected specimens for his collection. The scientist was the author of numerous articles and several multi-volume treatises, including one on pathologic anatomy and an atlas depicting human anomalies. His principal labors were devoted to the comparative morphology of vertebrates. In 1810 he completed the translation of Cuvier's (1769-1832) five-volume Leçons d'anatomie Comparée from French into German.

Meckel was a member of the German Academy of Naturalists "Leopoldina," a corresponding member of the Paris Academy of Sciences, and a foreign member of the Royal Society of London.

Jacob Christian Schäffer was a German inventor, naturalist, entomologist and mycologist.

Schäffer was a very versatile scientist. He is best known for his work in mycology (the study of fungi), but his most important publication was undoubtedly a book on daphnia or water fleas.

Schäffer also published reference books on pharmaceuticals and medicinal herbs. He conducted experiments on electricity, colors, and optics, and invented the manufacture of prisms and lenses. He invented the washing machine, designs for which he published in 1767, and studied ways to improve paper production.

Schäffer was a professor at the Universities of Wittenberg and Tübingen, a member of the Royal Society of London, and a correspondent of the French Academy of Sciences.

Johann Jakob Scheuchzer was a Swiss naturalist and geologist, paleontologist and fossil collector.

Scheuchzer studied at the University of Altdorf near Nuremberg, earned a doctorate in medicine at Utrecht University, and studied astronomy. He worked as a teacher, physician, and corresponded extensively with many scientists, writing several papers, including those on Swiss research, weather, geology, and fossils. Scheuchzer collected fossils during his extensive travels. And, as a proponent of diluvialism, he believed that all fossils and layers of the earth were formed by the Flood.

Between 1731 and 1735, Scheuchzer published a massive four-volume work called Physica Sacra, which is essentially a commentary on the Bible. It presented the facts of natural history along with passages of scripture. Thus Physcia Sacra attempted to reconcile the Bible with science.

This book is also called the "Copper Bible" because it contains over 750 magnificent color engravings on copper plates. These engravings are in themselves the pinnacle of engraving from the Baroque period. The illustrations depict scenes with biblical and scientific motifs. They were based on his own cabinet of natural history and other famous European cabinets of rare specimens. The engravings were produced by highly skilled engravers, including Georg Daniel Heumann and Johann August Corwin.

During his lifetime, Johann Jakob Scheuchzer wrote 34 scientific papers and many articles, and he was a member of the Royal Society.

Elihu Hubbard Smith is an American author, writer, and physician.

Smith graduated from Yale College as early as age 11 with a liberal arts education, followed by a medical degree. He worked at New York Hospital and published historical articles on plague and plague fevers.

Elihu Smith was a very active writer: he was a member of the Hartford Witters, wrote the first American comic opera "Edwin and Angelina" (1796), was the editor of the first book anthology of American poetry ("American Poems, Selected and Original," 1793) and the first national American medical journal ("Medical Repository"), and corresponded extensively with many writers and writers of his time.

Smith died at age 27 of yellow fever, which he contracted while treating patients during an outbreak in New York City.

Christoph Jacob Trew was a German botanist.

He was originally a city solicitor, court physician, Count Palatine of the Holy Roman Empire, an advisor to the Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach. He also had an academic passion for botany. He was a member of the Royal Society of London, the Berlin Academy, and the Florentine Botanical Society. His interest in botany then led him to sponsor the publication of illustrated botanical books.

Antonio Vallisneri the Elder was an Italian naturalist, physician and geologist, collector, and member of the Royal Society of London.

He studied in Bologna, Venice, Padua and Parma and headed the chair first of practical medicine and then of theoretical medicine at the University of Padua. In addition to medicine, Vallisneri conducted important research in the natural sciences. In particular, in the field of geology, he is credited with recognizing the organic nature of fossils unrelated to the Great Flood, which contributed to the end of centuries-old disputes. His observations on the water cycle, thermal waters and some mines in the Apennines were also important.

Vallisneri was interested in all branches of the natural sciences, collecting numerous collections of animals, minerals, and other natural objects during his lifetime. The scientist compiled a brief catalog of his collection, which was published in 1733 by his son, Antonio Vallisneri, Jr. The Vallisneri Museum included naturalistic finds, anatomical preparations, medical and scientific instruments, antiques, and exotics from various cultures and eras as well as geographical origins. In 1734, his son donated this museum to the University of Padua, initiating the creation of a general museum for the university.

Antonio Vallisneri Jr. followed in his father's footsteps and for many years held the position of professor of natural history at the University of Padua. He devoted his life to collecting and processing his father's writings and tidying up his library, which contained about a thousand volumes. These were donated to the University Library in Padua.

Johannes Eusebius Voet was a Dutch physician, poet, entomologist and illustrator.

Voet worked as a physician in Dordrecht and had a large collection of insects and shells. Studying beetles and other insects, he wrote Catalogus Systematicus Coleopterorum, Systematische naamlijst van dat geslacht der Insecten dat men Torren noemt, which was published in 1804-1806. It was one of the best entomological works published in the Netherlands. It contained numerous original hand-colored engravings, many of them by C.F.C. Kleemann, Rösel's son-in-law.

Nikolaus von Jacquin, full name Nikolaus Joseph Freiherr von Jacquin, also Baron Nikolaus von Jacquin, was an Austrian and Dutch scientist, professor of chemistry and botany, and director of the Vienna Botanical Garden.

Jacquin is considered a pioneer of scientific botany in Austria. He wrote fundamental works in botany, was the first to describe many plants, fungi, and animals, introduced experimental methods in chemistry, and successfully campaigned for the introduction of Linnaeus' system of plants in Austria. On behalf of Emperor Franz I, von Jacquin was in charge of the imperial gardens (including Schoenbrunn) and also led a scientific expedition to Central America from 1754 to 1759, from which he returned with an extensive collection of plants.

In 1768, Nikolaus von Jacquin was appointed professor of botany and chemistry at the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Vienna and director of the newly founded botanical garden, which he reorganized according to scientific principles. Nikolaus von Jacquin was a member of the Royal Society of London, a foreign honorary member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, and a correspondent of the Paris Academy of Sciences.

Samuel Thomas von Soemmering was a German physician, anatomist, anthropologist, paleontologist, physiologist and inventor.

He studied medicine at Göttingen, where he received his doctorate, and in the same year became professor of anatomy at Kassel, then at Mainz. Among Soemmering's contributions to biology are the discovery of the macula in the retina of the human eye, studies of the brain, lungs, nervous system, and embryonic malformations, and he published many papers in the fields of neuroanatomy, anthropology, and paleontology. He was the first to give a reasonably accurate account of the structure of the female skeleton.

Soemmering also worked on fossil crocodiles and pterodactyls, which at the time were called ornithocephalians. In addition, Soemmering dabbled in chemistry, astronomy, philosophy, and various other fields of science. Among other things, he investigated the refinement of wines and sunspots, and designed a telescope for astronomical observations. In 1809, Soemmering developed a sophisticated telegraph system based on electrochemical current, which is now preserved in the German Science Museum in Munich.