ID 1349758

Los 94 | Albert Einstein (1879-1955)

Schätzwert

£ 700 000 – 1 000 000

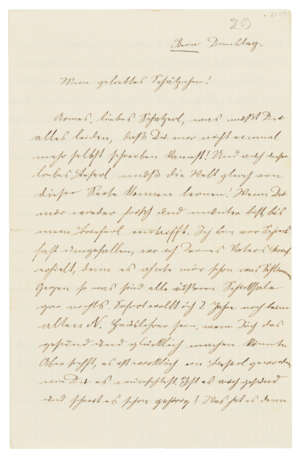

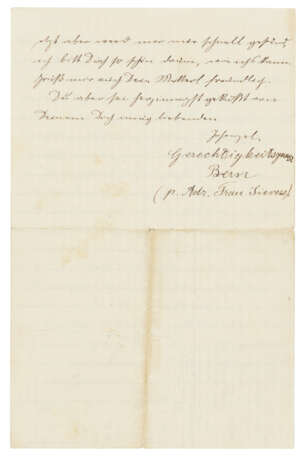

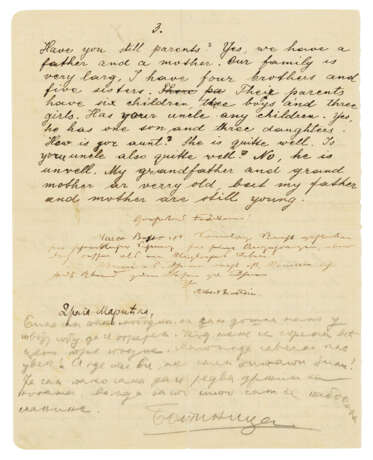

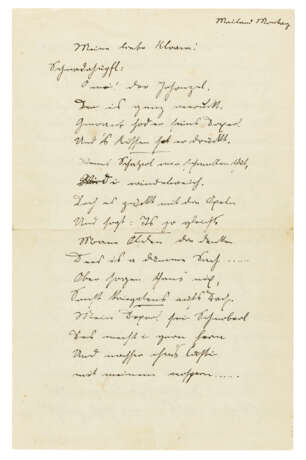

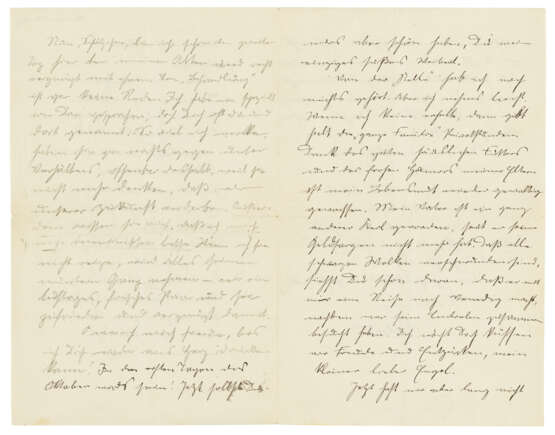

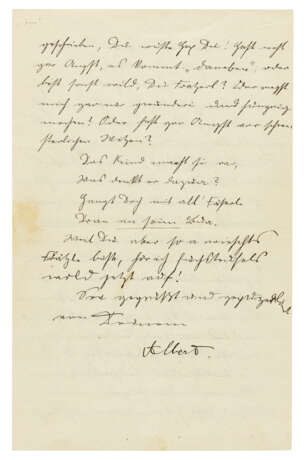

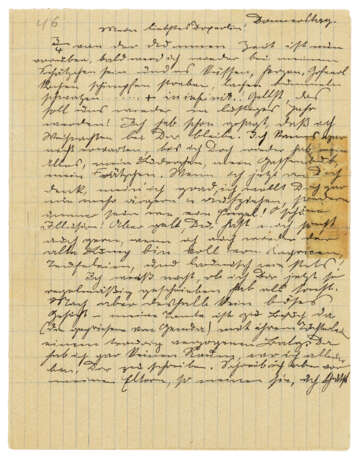

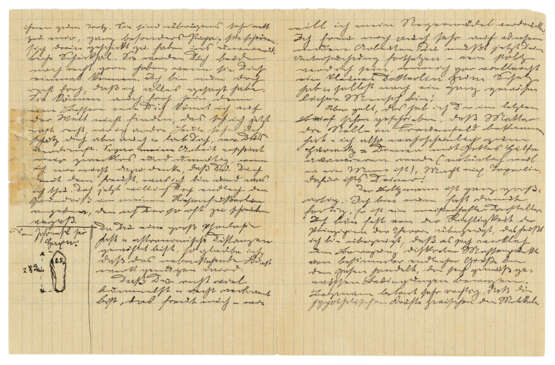

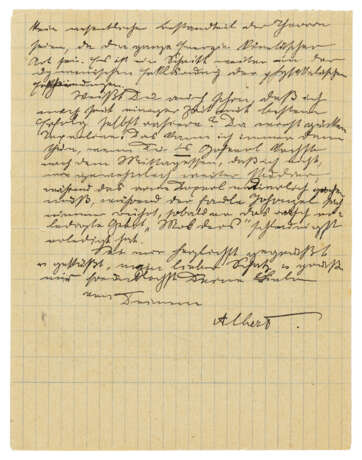

Series of 43 autograph letters signed ('Albert Einstein' (4), 'Albert' (23), the later letters with variations on the pet-name 'Johannzel', two letters lacking signature) to his first wife, Mileva Marić, [Zurich, Milan, Mettmenstetten, Melchtal, Winterthur, Schaffhausen and Bern, 16 February 1898 - ?19 September 1903]

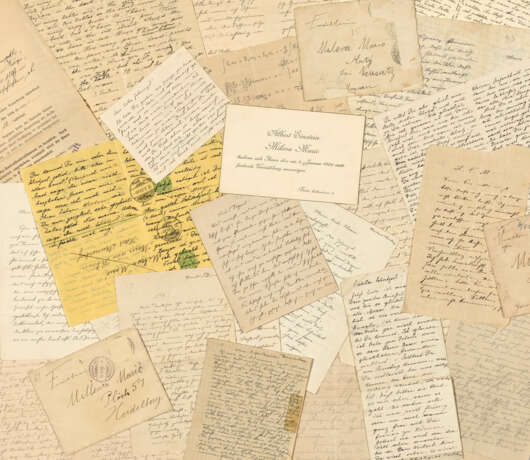

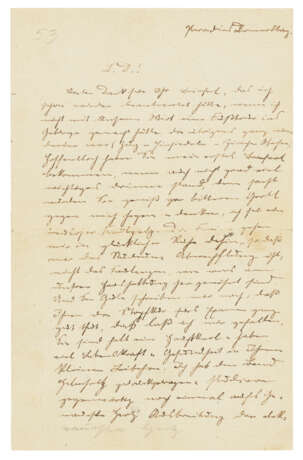

The letters addressed to Mileva initially with formality as 'Esteemed Miss!', later under a variety of pet-names, most often variations on 'Doxerl' ('doll' in south German dialect), altogether approximately 147 pages, various sizes (two letters fragments only), two with original envelopes, with one additional envelope, postmarked 2 January 1898. With ten autograph letters signed by Mileva Marić ('D', 'Toxerline', 'Weiberl', 'Dock', 'Doxerl', one unsigned) to Einstein, [Heidelberg, Kać, Zurich, Stein am Rhein and n.p., after 20 October 1897 - 13 November 1901], altogether 30 pages, various sizes; also a printed announcement of their marriage on 6 January 1903 (on card, 90 x 140mm) and a statement of a fine on Einstein by the Zurich city authorities, 23/28 April 1897, for residing in the city without valid identification papers. Provenance: by descent – Christie's New York, 25 November 1996, lot 3, bought by: – the present owner.

'I am more and more convinced that the electrodynamics of moving bodies, as presented today, is not correct'.

The Einstein Love Letters: the most important source for Einstein's early life and intellectual development, comprising almost half of Einstein's surviving correspondence up to the end of 1903, tracking the development of his early scientific thinking and his relationship with his first wife, Mileva Marić, including the only known information about their daughter Lieserl, born a year before their marriage.

The correspondence covers a formative period in Einstein's life: at the time of the earliest letter, in February 1898, he is not quite 19 years old, stateless, a student in his second year at Zurich Polytechnic: by the time of the last letter, in September 1903, he is married, the father of a secret child, an employee of the Federal Patent Office in Bern, the author of four published scientific papers, and is a mere eighteen months away from the first of his annus mirabilis papers.

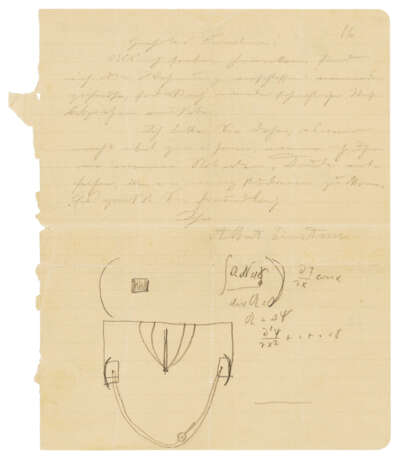

The recipient of the letters, Mileva Marić (1875-1948, later Marić-Einstein) was Serbian, three years older than Einstein, and a fellow student at the Polytechnic, where she was one of the earliest female students on the physics and mathematics course: they had met shortly after her enrollment in the autumn semester of 1896. Einstein's first letter to her is relatively formal – it begins 'Esteemed Miss!' – and welcomes the prospect of her return to Zurich after a winter semester spent in Heidelberg, summarising the course content she has missed, and providing an acidic pen-portrait of one of their teachers: 'Fiedler ... is the same indelicate, rude man as before & in addition sometimes opaque, but always witty & profound – in brief, a master, but, unfortunately, also a terrible schoolmaster'. Two letters over the subsequent months are interesting for being on reused pages which contain some of the earliest surviving scientific calculations by Einstein. By the following year, Einstein is writing from his parents' home in Milan during the spring holiday with his first intimations of independent scientific thought: 'My broodings about radiation are starting to get on somewhat firmer ground'. By summer that year, the deepening of his relationship with Mileva is evident: he writes from his summer holidays at Mettmenstetten (a resort in the canton of Zurich) about their shared 'marvellous household' in Zurich, of which Mileva is the 'mistress'. His letters that summer are full of his scientific reading ('Helmholtz on atmospheric movement ... Hertz's propagation of electric force') and contain the first, startling reference to his rethinking of 'the electrodynamics of moving bodies', which was to reach fruition with his 1905 paper of that title, introducing the special theory of relativity:

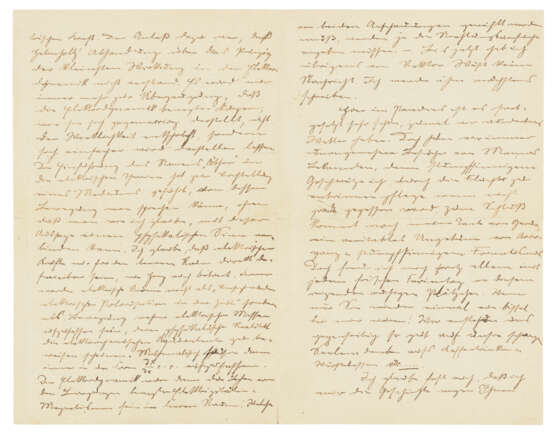

I am more and more convinced that the electrodynamics of moving bodies, as presented today, is not correct, and that it should be possible to present it in a simpler way. The introduction of the term 'ether' into the theories of electricity led to the notion of a medium of whose motion one can speak without being able, I believe, to associate a physical meaning with this statement. I think that the electric forces can be directly defined only for empty space (?10 August 1899)

On 10 September, he announces a 'good idea ... about a way of investigating how the bodies' relative motion with respect to the luminiferous ether affects the velocity of propagation of light in transparent bodies'; on 10 October he mentions further 'considerations about the study of the basic laws of thermoelectricity. I have also devised a method of great simplicity, which permits one to decide whether the latent heat in metals is to be reduced to the motion of ponderable matter or of electricity'.

The letters of 1900 show a marked change of tone: Einstein adopts the 'Du' form for the first time, and the letters are increasingly marked by use of a south-German dialect which the couple used as a private language; in later letters, Einstein addresses Mileva as 'Doxerl' and signs with variations of the name 'Johannzel'. Letters from the summer holidays of 1900, which he spent in Melchtal with his mother and sister after finishing his course at the Zurich Polytechnic, demonstrate that Einstein had informed them of his intention to marry Mileva, a source of significant family conflict: he reports his mother's first reaction, 'You are ruining your future ... That woman cannot gain entrance to a decent family'. In the autumn of that year, Einstein visits his parents in Italy, before returning to Zurich to work on a doctoral dissertation: his letters report investigations into 'the Thomson effect', and his studies of the work of Ludwig Boltzmann, and increasingly speak of his friendship with Michele Besso, who was to be a lifelong friend and scientific sounding board: 'I like him very much because of his sharp mind and his simplicity'. There is a reference to Einstein's first published scientific article on capillary phenomena, which he submitted to Annalen der Physik in December ('The results on capillarity ... seem to be totally new despite their simplicity ... If a law of nature emerges from this, we will send it to Wiedemann's Annalen').

By the beginning of 1901, Einstein is actively applying for teaching posts as an Assistent, with the aim of achieving sufficient financial stability to be able to marry Mileva, though he laments the difficulties caused by anti-semitism in Germany. A long letter of 23 March 1901 shows him ruminating on 'the latent kinetic energy of heat in solids and liquids' and the Dulong-Petit law; on 27 March he writes with a ringing declaration of his faith in their relationship, and an indication of Mileva's involvement in the development of his scientific thinking on what was to be special relativity: 'I know that of all people you love me the most deeply and understand me the best ... How happy and proud I shall be when the two of us together will have brought our work on relative motion to a victorious conclusion!'; the letter continues with a discussion in some scientific detail of his investigation into specific heat. In two letters on 4 and 10 April, he is reflecting on Max Planck's studies on radiation and Paul Drude's theory of electrons; Besso has joined him in Zurich, and Einstein rejoices in his 'extraordinarily fine mind, whose working, though disorderly, I watch with great delight. 'Yesterday evening ... we talked about the fundamental separation of luminiferous ether and matter, the definition of absolute rest, molecular forces, surface phenomena, dissociation'. That summer he obtains a teaching job in Winterthur during the absence on military service of Professor Rebstein, remarking humorously that he will be teaching 'about 30 hours a week, including even descriptive geometry, but the brave Swabian is not afraid'. The same letter (15 April 1901) also announces the first prospect of a job at the Federal Patent Office in Bern, and describes 'an extremely lucky idea' for applying his theory of molecular forces to gases (reflecting the subject matter of his second published paper in the following year). At the end of April, Einstein delights in the prospect of a holiday with Mileva at Lake Como in Italy: 'come to me to Como and bring along my blue dressing-gown, into which we can wrap ourselves'. It was during this holiday that Mileva became pregnant with their first child, and by late May, writing from Winterthur, Einstein's letters seek to comfort her, enquiring after her health and studies for the teaching diploma exams and her diploma dissertation ('How are our little son and your doctoral thesis?'). By the autumn of that year, their letters are referring to the future baby as 'Lieserl': Einstein by now is in Schaffhausen, where he is working as a tutor and continuing to reflect on molecular forces ('You know that no noticeable evolution of heat takes place when two neutral liquids are mixed together'); on 17 December he writes again that he is working 'very eagerly on an electrodynamics of moving bodies, which promises to become a capital paper. I wrote to you that I doubted the correctness of the ideas about relative motion. But my doubts were based solely on a simple mathematical error. Now I believe in it more than ever'. The year ends on a triumphant note, with the news that he has been invited to apply for a job at the Federal Patent Office in Bern: 'Our troubles have now come to an end'.

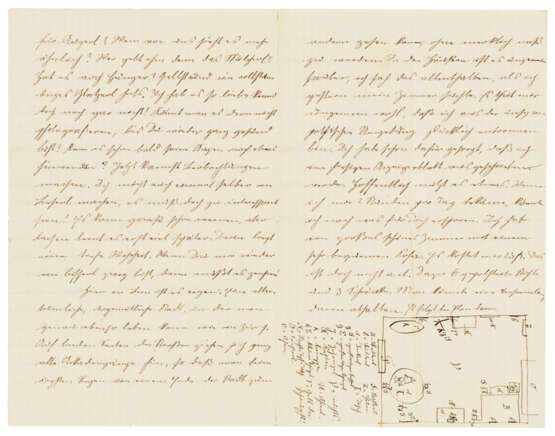

By the beginning of 1902, Einstein is settled in Bern waiting to start his job at the Patent Office (on 23 June), while Mileva has returned to Novi Sad in Serbia to give birth to their daughter. Einstein writes on 4 February 'You see, it has really turned out to be a Lieserl, as you wished. Is she healthy and does she already cry properly? What kind of little eyes does she have? Whom of us two does she resemble more?'. A high-spirited letter includes a sketch of the floor-plan of his room in Bern, 'a large beautiful room with a very comfortable sofa'. Only three further letters survive for 1902 (two fragmentary), mentioning his reading of Ernst Mach, and his friend Maurice Solovine, with whom he was to found the 'Olympia Academy' together with Conrad Habicht.

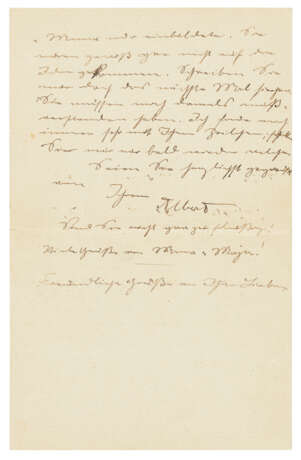

Albert Einstein and Mileva Marić married on 6 January 1903 – a card announcing their marriage is included in the lot. The last letter in the correspondence provides a coda to these eventful years, with a reference to Mileva's new pregnancy (their son Hans Albert was born on 14 May 1904) and discussing the illness of their daughter Lieserl: 'I am very sorry about what happened with Lieserl. Scarlet fever often leaves some lasting trace behind. If only everything passes well. How is Lieserl registered? We must take great care, lest difficulties arise for the child in the future'. Nothing further is known of Lieserl, and it is usually assumed that she died shortly after this date.

The chronological list of Einstein's correspondence in the Collected Papers (vol. 11) records 111 documents relating to Einstein dating before the end of 1903: of these, 54 are in the present lot, including nearly 60 per cent of his surviving letters from the years 1900-1902 in which he published his first scientific papers.

Published in the Collected Papers: a full list of letters in the lot is available on request. Note that the lot does not include an autograph postcard from Mileva to Albert Einstein, 27 August 1903, which is in Brandeis University Library.

| Künstler: | Albert Einstein (1879 - 1955) |

|---|---|

| Herkunftsort: | Westeuropa, Deutschland, Europa, Schweiz |

| Kategorie des Auktionshauses: | Briefe, Dokumente und Manuskripte, Medizin und Wissenschaft, Bücher und Handschriften |

| Künstler: | Albert Einstein (1879 - 1955) |

|---|---|

| Herkunftsort: | Westeuropa, Deutschland, Europa, Schweiz |

| Kategorie des Auktionshauses: | Briefe, Dokumente und Manuskripte, Medizin und Wissenschaft, Bücher und Handschriften |

| Adresse der Versteigerung |

CHRISTIE'S 8 King Street, St. James's SW1Y 6QT London Vereinigtes Königreich | |

|---|---|---|

| Vorschau |

| |

| Telefon | +44 (0)20 7839 9060 | |

| Aufgeld | see on Website | |

| Nutzungsbedingungen | Nutzungsbedingungen |