ID 832086

Los 22 | Fernand Léger (1881-1955)

Schätzwert

€ 400 000 – 600 000

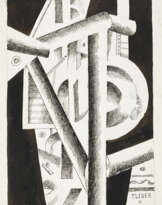

Composition à la poupée

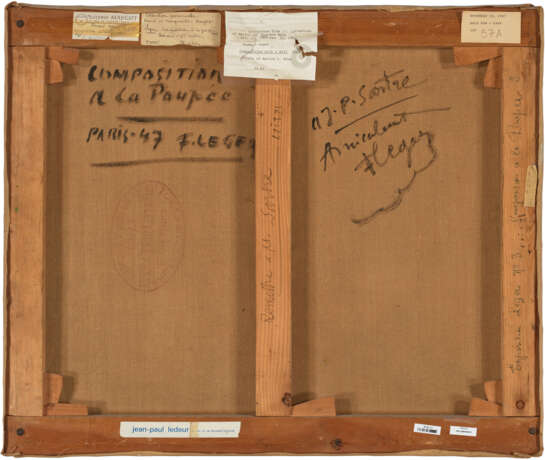

signé 'F. LEGER’ (en bas à droite); signé, daté et inscrit ‘Composition a la Poupée PARIS-47 F. LEGER a J. P. Sartre Amicalement FLeger’ (au revers)

huile sur toile

54.4 x 65.2 cm.

Peint en 1947

signed ‘F. LEGER’ (lower right); signed, dated and inscribed ‘Composition a la Poupée PARIS-47 F. LEGER a J. P. Sartre Amicalement FLeger’ (on the reverse)

oil on canvas

21 3/8 x 25 5/8 in.

Painted in 1947

Provenance

Jean-Paul Sartre, Paris (don de l'artiste).

Aimé et Marguerite Maeght, Paris.

Galerie Maeght, Paris.

Gustave et Marion Ring, Washington, D.C.

Collection particulière, États-Unis (par descendance).

United Jewish Appeal Federation of Greater Washington, Washington D.C. (don de celle-ci vers 1986); vente, Christie’s, New York, 10 novembre 1987, lot 57A.

Acquis au cours de cette vente par le propriétaire actuel.

Literature

G. Bauquier, Fernand Léger, Catalogue raisonné de l’œuvre peint, 1944-1948, Paris, 2000, vol. VII, p. 186, no. 1274 (illustré en couleurs, p. 187).

Exhibited

Paris, Musée national d’art moderne, Fernand Léger, Exposition rétrospective, 1905-1949, octobre-novembre 1949, no. 83 (erronément daté '1944').

Bâle, Galerie Beyeler, F. Léger, août-octobre 1969, no. 46.

Washington, D.C., Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Selections from the Collection of Marion and Gustave Ring, octobre 1985-janvier 1986, no. 24 (illustré en couleurs).

Special notice

Artist's Resale Right ("droit de Suite").

If the Artist's Resale Right Regulations 2006 apply to this lot, the buyer also agrees to pay us an amount equal to the resale royalty provided for in those Regulations, and we undertake to the buyer to pay such amount to the artist's collection agent.

ƒ: In addition to the regular Buyer’s premium, a commission of 5.5%

inclusive of VAT of the hammer price will be charged to the buyer.

It will be refunded to the Buyer upon proof of export of the lot

outside the European Union within the legal time limit.

(Please refer to section VAT refunds)

Post lot text

Alors que la Seconde Guerre mondiale fait rage en Europe, Léger se réfugie à New York et sillonne les États-Unis. Si ces cinq années d'exil bouleversent sa vision du monde, il est, néanmoins, très vite empli d'espoir dès son retour en France en décembre 1945. Dans « L'Art et le peuple », article paru dans la revue Arts de France en 1946, l'artiste déclare : « Je veux vous dire ce que j’ai éprouvé en revenant en France […], la joie que j’ai eue de retrouver mon pays […] Je vous assure que le peuple a fait un grand pas en avant en France. Je vous assure qu'une merveilleuse évolution a eu lieu. Peut-être que vous qui êtes restés ici, vous ne le ressentez pas. Moi, j'ai foi en la France » (cité in E.F. Fry, ed., Fernand Léger, Functions of Painting, New York, 1973, p. 147-148).

Peu de temps après son arrivée, Léger rejoint le Parti communiste, dont Picasso est membre. C'est sans doute par ce biais qu'il rencontre Jean-Paul Sartre, auquel cette Composition à la poupée est dédiée. Bien que l'écrivain et philosophe existentialiste n'ait jamais officiellement adhéré au parti, il n'en demeure pas moins profondément marxiste, et s'impose comme l'une des figures intellectuelles les plus influentes au sein des courants progressistes bourgeonnants. C'est dans l'incertitude de ces années d'après-guerre que Léger affirme plus que jamais la vocation sociale de sa peinture. Il est persuadé que l'une des clés de la reconstruction collective en ces temps de paix consiste à insuffler un sentiment de joie et de liberté dans la vie de ses concitoyens de tous bords. Autant d'idées que l'artiste a déjà prônées au milieu des années 1930, sous le Front Populaire : « Libérer les masses populaires, écrit-il alors, leur donner une possibilité de penser, de voir, de se cultiver et elles pourront, à leur tour, jouir pleinement des nouveautés plastiques que leur offre l’art moderne » (cité in S. Wilson, ‘Fernand Léger, Art and Politics, 1935-1955’, in Fernand Léger, The Later Years, cat. exp., Whitechapel Art Gallery, Londres, 1987, p. 58).

La dédicace qui apparaît au dos de Composition à la poupée – « à J. P. Sartre Amicalement FLeger » – suggère que le peintre en fit don au philosophe en gage de leur amitié et de leur foi partagée en un avenir social meilleur. Si Sartre conçoit la littérature comme le moyen le plus efficace de véhiculer sa pensée existentialiste et marxiste, pour Léger, ce sont avant tout les arts plastiques qui sont vecteurs de changement, dans la mesure où leur impact visuel peut rendre accessible au plus grand nombre – avec aplomb, éclat et lisibilité – l'image d'une société fondée sur des valeurs plus justes. La vie moderne requiert selon l'artiste une esthétique qui soit non seulement adaptée à la vitesse étourdissante de la réalité, mais qui puisse aussi, grâce à sa pureté plastique, offrir une sorte de répit des sens au travailleur, en distillant de l'harmonie et de la beauté dans son quotidien. « Dès le départ, note Ina Conzen-Meairs, Léger était persuadé que le rôle de l'art était de répondre aux besoins de l'homme moderne, qui avait coupé ses liens avec la spiritualité dans sa quête d'un 'substitut de la religion'. Cela devait impérativement passer par une amélioration de la qualité de vie du travailleur » (in ‘Revolution and Tradition The Metamorphosis of the Conception of Realism in the Late Works of Fernand Léger’, in op. cit., cat. exp., 1987, p. 13-14).

Dans Composition à la poupée, Léger reformule l'abstraction de ses années antérieures pour la mettre au service d'un langage plastique plus intelligible, qui sublime les objets les plus ordinaires. Au centre de la toile, un foisonnement de pages semble s'échapper d'un livre – en allusion, sans doute, aux abondants écrits de Sartre. La couverture de l'ouvrage est ornée de symboles mystérieux, dont les lignes géométriques résonnent avec les différentes formes alentour, de la plus ondulante et organique à la plus linéaire et artificielle, apportant clarté et cohésion à l'ensemble. Sur la gauche, la poupée éponyme nous fixe par-delà la toile d'un regard à la fois vide et envoûtant. Si le dégradé de gris qui sculpte sa chevelure produit une vague impression de mouvement et de vie, la vacuité de ses yeux et le rose saumon vif de sa peau soulignent bien sa nature inanimée. Son expression de marbre renvoie sans doute subtilement à L'Être et le néant : dans son essai de 1943, Sartre s'appuie notamment sur la métaphore du masque pour analyser le conflit entre conformisme et authenticité de l'être. Par l'intermédiaire du philosophe, Léger rencontre sûrement Simone de Beauvoir, déjà plongée en 1947 dans l'écriture de son grand traité féministe, Le Deuxième sexe. Celle qui partage la vie de Sartre est également cette fervente existentialiste qui lutte pour libérer la femme de ses carcans et de la chosification que la société lui inculque. Aussi, le jouet du présent tableau rend-il sans doute hommage à son discours, qui compare volontiers la femme moderne à une poupée d'enfant : conditionnée pour s'habiller, agir et vivre selon des préceptes masculins.

Que ce soit par l'art ou par l'écriture, Léger, Sartre et de Beauvoir se battent tous trois pour affranchir leurs semblables du joug du système. Les jaunes, bleus, verts et rouges emblématiques de Léger jaillissent ici du fond neutre de la toile, comme pour crier haut et fort le « rôle social majeur » que la couleur se doit de jouer. « Elle participait à enrober les réalités monotones du quotidien, constate Gilles Néret. Elle habillait le réel. Les objets les plus modestes pouvaient faire et faisaient appel à la couleur pour qu'elle change la manière dont les gens percevaient leur véritable utilité » (in F. Léger, New York, 1993, p. 195).

C'est à travers la métaphore de la couleur que Léger traduit l'espoir qu'il place dans le citoyen ordinaire, mais aussi dans le langage réaliste de la peinture, capable par sa franchise formelle de toucher l'homme dans son plus for intérieur ainsi que le monde qui l'entoure. « L'empathie, nous rappelle Conzen-Meairs, se trouve au fondement même de l'idée du réalisme que défend Léger ». Dans les années 1940, cependant, ce « ne sont plus les préoccupations purement artistiques qui dominent, mais bien la volonté de produire un art d'une plus grande lisibilité et d'un impact plus retentissant... pour exprimer l'espoir de voir l'homme s'affranchir un jour de son asservissement à la machine et au système, pour enfin se réaliser, libérer son esprit et accéder à une dignité nouvelle » (in op. cit., cat. exp., Londres, 1987, p. 12-14). Aux yeux de Léger, l'art est le meilleur moyen pour l'homme d'échapper au vrombissement monotone, abrutissant de l'existence moderne – « l'absurde » de Sartre – et de s'ouvrir enfin à l'immensité des libertés.

The five years of exile during the Second World War that Léger spent in New York and traveling around America had been an eye-opening experience. Nevertheless, when he returned to France in December 1945, he was immediately filled with a renewed sense of hope. In "Art and the People," an 1946 article published in the journal Arts de France, Léger declared, "I want to tell what I felt in returning to France, the joy I have had in rediscovering my country... I assure you that the people have made a great advance in France. I assure you that a magnificent evolution has come about. Maybe you who stayed here don't feel it. Me, I have faith in France" (quoted in E.F. Fry, ed., Fernand Léger, Functions of Painting, New York, 1973, pp. 147-148).

Like Picasso, Léger joined the French Communist Party upon his return, and it was likely through this mutual affiliation that the artist met the renowned existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre, to whom Composition à la poupée is dedicated. While Sartre never formally joined the Communist party, he was himself a devout Marxist and integral intellectual figure for these burgeoning tides of social change. More so now than ever, it was in these uncertain post-war years that Léger positioned himself as a painter with a definite social agenda. He believed that an essential part of peacetime reconstruction was to bring a sense of enjoyment and freedom to the lives of citizens from all walks of life. He had advocated similar ideas in the mid-1930s, during the time of the leftist Front Populaire, writing, "Liberate the mass of people, give them a chance to think, to see, to cultivate their tastes. They will be able in their turn to enjoy to the full all the latest inventions of modern art" (quoted in S. Wilson, ‘Fernand Léger, Art and Politics, 1935-1955’, in Fernand Léger, The Later Years, exh. cat., Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, 1987, p. 58). Dedicated on the reverse ‘a J. P. Sartre Amicalement F Leger,’ Composition à la poupée was likely gifted to Sartre by the artist, a token of their friendship and shared hope for a socially liberated future. Whereas Sartre found literature to be the most effective communicator of his existentialist and Marxist ideas, for Leger art was the ultimate agent of change, capable of communicating to the masses in bold, legible terms the vision of a new and collective society. This new reality demanded an art that could not only keep pace with the speed of modernity but also, through the purity of its plastic beauty, provide a kind of aesthetic relief from the toils of the working man's labor. "From the beginning," Ina Conzen-Meairs has observed, "Léger was convinced that the role of art was to support modern man, who had lost his religious connections, in his search for a 'substitute for the diminished religion.' It should mean a heightening of the quality of life for the working man" (in ‘Revolution and Tradition, The Metamorphosis of the Conception of Realism in the Late Works of Fernand Léger’ in op. cit., exh. cat., 1987, p. 13-14).

Here, the abstraction of Leger’s earlier aesthetic is updated and made increasingly accessible, magnifying the otherwise humble, everyday object to new artistic heights. At the centre of the canvas, pages spill forth from a bound book, a likely nod to the many writings of Sartre. Anonymous symbols grace its cover, each of which echoes the surrounding forms–whether spiraling and organic or linear and manufactured–found throughout the composition, providing a visual cohesion and clarity. To the left, the titular poupée, or doll, gazes out, her stare equally vacant as captivating. Although gradient modelling imbues her hair with a suggestion of life, her hollow eyes and deep salmon skin readily reiterate her inanimate state. Her mask-like face seems to subtly allude to Sartre’s 1943 L’être et le néant, in which he expresses the conflict between conformity and an authentic way of being through the metaphor of a mask. Through Sartre, Leger was likely acquainted with the philosopher’s lifelong partner and great love, Simone de Beauvoir, who by 1947 was fast at work writing her celebrated feminist treatise, The Second Sex. Like Sartre, she too was a devoted existentialist, herself searching to liberate her fellow women from society’s imposition and learned objectification. The poupée here is perhaps a reference to her own writings and frequent likening of the modern woman to a child’s doll: conditioned to dress, act and live in accordance with the male standard.

Artist and philosophers alike, all three advocated for the liberation of mankind from the weighty limitations of society. The emblematic yellows, blues, greens and reds emerge from the muted background in the present picture, emphatically underlining the "major social role" that colour had to accomplish, as Gilles Néret has observed. "It contributed to enveloping the monotonous everyday realities. It dressed reality. The humblest objects could be and were calling out for colour to change the way people perceived their real purpose" (in F. Léger, New York, 1993, p. 195). Through the metaphor of colour, Léger's realism stood for his belief in the common man and in the formal efficacy of realism to reach him at home and in his world. "To have the common touch was," Conzen-Meairs reminds us, "part of Léger's conception of realism from the very beginning." By the 1940s, however, it is "no longer the purely artistic that stands in the foreground, but the hope for a greater intelligibility and a broader impact for his art...it is an expression of the hope that man will not remain the slave of the machine, and the system, but that he will have the possibility to realise himself and to liberate his spirit in order to ascend to a new dignity" (in exh. cat., op. cit., London, 1987, p. 12-14). For Léger, it is art that provides the means through which to escape the banal, stigmatic hum of modern society—what Sartre deemed the absurd—and to embrace the infinity of freedoms.

| Künstler: | Fernand Léger (1881 - 1955) |

|---|---|

| Angewandte Technik: | Öl auf Leinwand |

| Kategorie des Auktionshauses: | Gemälde |

| Künstler: | Fernand Léger (1881 - 1955) |

|---|---|

| Angewandte Technik: | Öl auf Leinwand |

| Kategorie des Auktionshauses: | Gemälde |

| Adresse der Versteigerung |

CHRISTIE'S 8 King Street, St. James's SW1Y 6QT London Vereinigtes Königreich | |

|---|---|---|

| Vorschau |

| |

| Telefon | +44 (0)20 7839 9060 | |

| Aufgeld | see on Website | |

| Nutzungsbedingungen | Nutzungsbedingungen |