ID 929407

Los 7 | Man Ray (1890-1976)

Schätzwert

€ 2 200 000 – 3 200 000

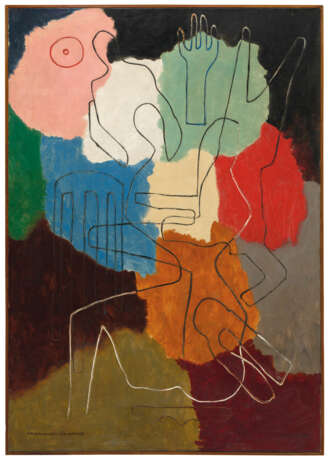

Les Gens en colère d'un après-midi

signé et daté 'man Ray 1928' (en bas à droite) et inscrit 'Les gens en colère d'un après-midi' (en bas à gauche)

huile sur toile

162 x 114 cm.

Peint en 1928

signed and dated 'man Ray 1928' (lower right) and inscribed 'Les gens en colère d'un après-midi' (lower left)

oil on canvas

63 3/4 x 44 7/8 in.

Painted in 1928

Provenance

Lee Miller (don de l'artiste en 1932 et jusqu'à au moins l'automne 1937).

Collection particulière, Le Caire.

Mina Sarofim, Le Caire (vers 1962-64); vente, Sotheby's, Londres, 3 février 2004, lot 78.

Acquis au cours de cette vente par le propriétaire actuel.

Literature

'Le Surréalisme en 1929', in Variétés, Bruxelles, juin 1929, No. Hors Série. (illustré).

T. H. Cochran, 'An Australian in London', in The Home, Australie, 1er septembre 1936, p. 34 (illustré in situ dans l'exposition de 1936 à Londres).

Man Ray, Self Portrait, Prague, 1968, p. 168 (illustré).

R. Penrose, Scrap Book, 1900-1981, Londres, 1981, p. 66, fig. 162 (illustré in situ dans l'exposition de 1936 à Londres).

D. Sylvester, éd., René Magritte, Catalogue raisonné, Oil, Paintings and Objects, 1931-1948, Londres, 1993, vol. II, p. 48 (illustré in situ dans l'exposition de 1936 à Londres, fig. 40).

Surrealism, Revolution by Night, cat. exp., National Gallery of Art, Canberra, 1993, p. 312 (illustré in situ dans l'exposition de 1936 à Londres).

Exhibited

Paris, Galerie Van Leer, Man Ray, 1928, no. 1.

Londres, New Burlington Galleries, The International Surrealist Exhibition, juin-juillet 1936, p. 27, no. 312 (titré 'Folk Irritated About an Afternoon').

Francfort, Frankfurter Kunstverein et Bâle, Kunsthalle, Man Ray, Inventionen und Interpretationen, octobre 1979-février 1980, p. 185, no. 17.

Tokyo, The Bunkamura Museum of Art; Takamatsu, City Museum of Art; Tsukuba, Museum of Art, Ibaraki; Okayama, Prefectural Museum of Art; Akita, Senshu Museum of Art et Itami, City Museum of Art, Man Ray et ses amis, juillet 1991-février 1992, p. 38, no. 46 (illustré en couleurs).

Special notice

Artist's Resale Right ("droit de Suite").

If the Artist's Resale Right Regulations 2006 apply to this lot, the buyer also agrees to pay us an amount equal to the resale royalty provided for in those Regulations, and we undertake to the buyer to pay such amount to the artist's collection agent.

ƒ: In addition to the regular Buyer’s premium, a commission of 5.5%

inclusive of VAT of the hammer price will be charged to the buyer.

It will be refunded to the Buyer upon proof of export of the lot

outside the European Union within the legal time limit.

(Please refer to section VAT refunds)

This item will be transferred to an offsite warehouse after the sale. Please refer to department for information about storage charges and collection

details.

Post lot text

« La belle peinture ça ne m’intéresse pas car de toute façon les Anciens ont fait quelque chose qu’on ne pourra plus atteindre. La seule chose qu’on peut faire maintenant, c’est faire quelque chose de différent. C’est ça qui a de la valeur. »

Man Ray

Peu d’artistes du XXème siècle n’ont montré d’éclectisme plus protéiforme que Man Ray ! Remarquable par la merveilleuse créativité qui était la sienne, Man Ray caractérise l’idée même de l’artiste d’avant–garde : l’inventivité, l’audace, l’imaginaire et la remise en question des conventions artistiques. Plus connu comme photographe par le grand public, Man Ray est l’auteur d’une impressionnante oeuvre peinte à la puissance évocatrice. La peinture est une constante de la carrière de cet homme aux talents multiples, qui parle de la peinture comme d’un prolongement de la photographie et qui montrera autant de génie à explorer de nouvelles techniques picturales. Man Ray durant toute sa vie ne cesse de basculer entre ces deux pratiques, mais a toujours eu le profond désir de rentrer dans l’histoire de l’art par la peinture.

Les années vingt furent pour Man Ray une époque particulièrement intense de création. Il est depuis peu à Paris (juillet 1921) et travaille comme photographe de mode et portraitiste. Il immortalise les visages des artistes et écrivains les plus en vue du Tout-Paris des années folles. Mais la photographie est bien plus qu’un moyen de subsistance pour l’artiste. Fourmillant d’idées, il développe d’autres formes de création assimilables : la rayographie, le photo-montage et la solarisation. Man Ray fut sans nul doute à cette période, le maître en matière d’exploration de la photographie comme mode de communication, de provocation et de documentation esthétique.

Précurseur du dadaïsme en Amérique, il se rapproche à Paris des Surréalistes, dont il partage les idées modernes tout en conservant une liberté d’esprit absolue. Man Ray participe à la première exposition surréaliste de 1925, qui a lieu à la Galerie Pierre et qui réunit des artistes comme Jean Arp, Max Ernst, André Masson, Joan Miró ou encore Pablo Picasso. Il illustre de ses photographies mais aussi de ses collages et dessins les ouvrages d’André Breton, Paul Éluard, Marcel Duchamp… En 1928, il réalise son premier court métrage surréaliste l’Étoile de Mer avec un scénario de Robert Desnos. Cette même année, Man Ray mettra fin à sa relation tumultueuse avec l’icône de la glamour parisienne, Kiki de Montparnasse, avant de rencontrer la ravissante Lee Miller (1907-1977) – elle aussi, photographe surréaliste et mannequin – qui deviendra sa compagne et son assistante pendant les trois prochaines années. Man Ray est heureux de retourner à la peinture qui reprend un rôle central dans son travail à la fin des années vingt.

Man Ray n’oppose pas la photographie à la peinture, mais les considère comme des arts complémentaires auxquels il a recours en fonction de son désir d’expression. Son expérience photographique -au sens large- comporte des travaux innovants comme la rayographie qui consiste à disposer un assortiment d’objets sur un papier sensible et à l’exposer à la lumière. La surimpression permet à plusieurs images d’être fixées sur le même support. Cette technique donne naissance à des œuvres mystérieuses et des compositions poétiques totalement abstraites. Leur puissance expressive permet à l’artiste de réaliser la fusion entre la photographie et l’art pictural. Il n’est donc pas surprenant que la peinture s’inspire à son tour de cette esthétique.

Les Gens en colère d'un après-midi est un parfait exemple de ce transfert. Les silhouettes indéchiffrables laissées par les objets fixés par la lumière sur le papier sensible sont ici reproduites par la surimpression d’une ligne de dessin sur une base préparée. Le fond coloré remplace le support-papier où vient s’imprimer un dessin en superposition, comme gravé par l’exposition à la lumière. Comme dans les rayographes, la présente composition résulte de deux étapes distinctes : la fabrication du fond et la surimposition des formes secondaires. L’artiste utilise également ce dispositif dans les tableaux Le Roman Noir, 1939 et Les Lesbiennes, 1938 pour mettre en relief le sujet.

L’opposition fondamentale lumière/ombre qui régit les recherches photographiques de Man Ray est très présente dans cette œuvre. Le dessin est à peine esquissé dans une teinte opposée à celle du fond. Son trait apparaît en sombre sur les zones claires et en foncé sur les aplats de couleurs claires. Le graphisme svelte et subtil émerge spontanément sur le fond coloré et donne une impression d’éphémère et de fraicheur particulière à ces œuvres. Par ailleurs, la force des contrastes simule le mouvement dans ces compositions résolument dynamiques, comme si le trait fin et fragile était rentré en résistance avec la massivité du fond brut. Man Ray inscrit ici le mouvement dans la superposition d’images ainsi que les cubistes et les futuristes suggéraient de le faire, comme dans le Nu descendant l’escalier, 1912 de son ami Marcel Duchamp. Man Ray met aussi en image une pratique cinématographique empruntée à certains de ses films (Emak Bakia, 1926 et Retour à la raison, 1923) où il passe systématiquement de l’objectif au subjectif, du plan éloigné au gros plan pour marquer de manière délibérée le passage du rêve à la réalité.

Pour essayer de mieux percevoir cette œuvre, on peut s’interroger sur la part de l’improvisation dans cette composition, si elle est le résultat d’une écriture automatique sans contrôle de la raison ? Bien sûr, cette question restera sans réponse ferme et définitive, mais il est vrai que si l’œuvre paraît décourager notre raison, elle réjouit nos sens ! L’émotion est instinctivement transmise par les procédés picturaux et non contenue dans le narratif du tableau. La disposition aléatoire des taches de couleurs et la silhouette affirmée des sujets semblent spontanées évoquant l’écriture mécanique qui est le meilleur moyen de laisser parler l’inconscient d’après André Breton. Le titre Les Gens en colère d’un après-midi prolonge cette interrogation sur le caractère surréaliste de cette oeuvre. Sa formulation énigmatique reflète-t-elle le penchant d’artistes tels que Picabia ou Magritte de doter leurs compositions de dénominations absurdes ou totalement désynchronisés de leur sujet ou est-elle juste la traduction maladroite de l’intitulé par un américain vivant en France depuis quelques années seulement ? Dès le premier regard, la présente composition trouble l’esprit auquel elle adresse des messages simultanés, mais néanmoins disjoints. D’une part le fond de l’œuvre figurant un paysage de taches colorées évoque la gaité et la légèreté et d’autre part, les motifs composés d’un enchevêtrement inintelligible d’éléments du corps humain, évoquent le chaos, la dispute et le déchirement. Dans cette œuvre, l’artiste nous invite à un questionnement résolument moderne sur le pouvoir de la ligne, de l'espace et de la forme. Si dix années séparent ces œuvres, il semble utile de rapprocher le présent tableau d’une toile majeure de cet artiste, La Danseuse de corde s’accompagne de ses ombres, 1916. Les deux œuvres témoignent de l’apport de l’artiste à l’art conceptuel et abstrait. Man Ray affirme que ce tableau n’est pas le résultat d’une idée préconçue mais qu’il est né d’une découverte due au hasard. Il l’aurait composé à partir de papiers découpés aux formes irrégulières récupérés au sol et qui possédaient une telle force visuelle qu’il décida d’en peindre un tableau. L’artiste dispose par la suite le motif de la danseuse ainsi que les cordes qui la relient à ses ombres. La technique du collage était fortement appréciée des surréalistes pour qui elle permettait l’exploitation de la rencontre fortuite de deux réalités distinctes. Dans Les Gens en colère d'un après-midi, la juxtaposition des taches de couleurs voque cette même force visuelle et procure une incontestable puissance suggestive. Dans les deux œuvres, la surimposition est utilisée pour créer l’illusion du relief. La liberté de la touche et l’emploi de la couleur dans ces deux tableaux jettent les bases d’une nouvelle représentation du réel qui permet à la présente œuvre de s'aborder dans un esprit résolument abstrait. En explorant de cette façon les propriétés physiques d’une peinture, l’artiste attire l’attention sur la bi-dimensionnalité inhérente des tableaux et instaure une autre manière de regarder une œuvre.

Dans un geste typiquement surréaliste, Man Ray sollicite le spectateur par un choc visuel et conceptuel. Il n’est donc guère surprenant que Les Gens en colère d’un après-midi, ait été l’une des peintures phares exposées à l’exposition charnière en Angleterre du Surréalisme en 1936 aux Burlington Galleries de Londres, où l’œuvre était référencée sous le titre Folk Irritated about An Afternoon. Dans ce tableau monumental, Man Ray tend à supprimer l’autorité absolue de la main de l’artiste pour engager activement le public dans la lecture de l’œuvre. L’impact de la lumière, des couleurs et les impressions personnelles sont privilégiées par rapport à la saisie du modèle pour créer l’émotion. Cette posture tellement moderne et novatrice, rejoint les grandes innovations de l’art moderne qui remettent en cause les conventions picturales. Par la négation ou tout du moins le questionnement de sa forme, Man Ray contribue grandement à l’affirmation d’une réalité picturale plus vaste et plus libre.

“I’m not interested in beautiful painting because, in any case, the Ancients did something that we can no longer achieve. The only thing we can do now is to do something different. That's what's valuable.”

Man Ray

Few 20th century artists have shown more protean eclecticism than Man Ray! Remarkable for his wonderful creativity, Man Ray typifies the very idea of the avant-garde artist with his inventiveness, audacity, imagination and questioning of artistic conventions. Although better known to the general public as a photographer, Man Ray also produced an impressive and evocative collection of paintings. Paintings are a constant throughout the career of this multi-talented man. He spoke about painting as an extension of photography and showed equal genius in exploring new pictorial techniques. Throughout his life, Man Ray kept switching between these two practices, but always with a deep desire to enter the history of art through painting.

The 1920s were a particularly intense creative period for Man Ray. He had recently moved to Paris (July 1921) and was working as a fashion and portrait photographer. He immortalised the faces of the most prominent artists and writers among the Parisian elite in the Roaring Twenties. However, photography was much more than a way to make a living for the artist. He was full of ideas and developed other similar creative forms such as rayographs, photo-montage and solarisation. Man Ray was at this time undoubtedly the master of exploring photography as a means of communication, provocation and aesthetic documentation.

A precursor of Dadaism in America, he became close with the Surrealists in Paris, whose modern ideas he shared while retaining an absolute freedom of spirit. Man Ray participated in the first Surrealist exhibition in 1925, which took place at the Galerie Pierre and brought together artists such as Jean Arp, Max Ernst, André Masson, Joan Miró and Pablo Picasso. He illustrated the works of André Breton, Paul Éluard, Marcel Duchamp and others with his photographs, collages and drawings. In 1928, he made his first surrealist short film, l’Étoile de Mer, with a script by Robert Desnos. That same year, Man Ray ended his tumultuous relationship with the Parisian glamour icon Kiki de Montparnasse before meeting the lovely Lee Miller (1907-1977) - also a surrealist photographer and model - who became his partner and assistant for the next three years. He was happy to return to painting as it once again played a central role in his work in the late 1920s.

Man Ray did not see photography in opposition to painting, but rather as complementary arts which he used according to how he wished to express himself. His photographic experience - in the broadest sense - includes innovative work such as rayographs, which involve arranging an assortment of objects on photographic paper and exposing them to light. Superimposition allows several images to be captured on the same medium. This technique produces mysterious pieces and totally abstract poetic compositions. Their expressive power allows the artist to achieve a fusion between photography and pictorial art. It is therefore not surprising that the painting is also inspired by this aesthetic.

Our piece is a perfect example of this transfer. The indecipherable silhouettes left by the objects captured by light on the photographic paper are reproduced here by superimposing a line drawn on a prepared base. The coloured background replaces the paper medium on which a drawing is superimposed, as if engraved by exposure to light. As with rayographs, our composition is the result of two distinct stages. Firstly producing the background and then superimposing the secondary shapes. The artist also uses this technique in the paintings Le Roman Noir, 1939 and Les Lesbiennes, 1938 to emphasise the subject.

The fundamental contrast between light and shadow that governs Man Ray's photographic research is very clear in this work. The drawing is lightly sketched in a colour that contrasts with the background. The line appears black on the light areas and dark on the light-coloured plates. The slender and subtle graphics emerge spontaneously on the coloured background and give these pieces a particular feeling of ephemerality and freshness. Moreover, the strength of the contrasts simulates movement in these particularly dynamic compositions, as if the thin and fragile line had met resistance with the immensity of the rough background. Here, Man Ray depicts movement by superimposing images as the Cubists and Futurists suggested doing, as in his friend Marcel Duchamp's Nu descendant l’escalier, 1912. Man Ray also uses a cinematographic practice borrowed from some of his films (Emak Bakia, 1926 and Retour à la raison, 1923) in which he systematically moves from the objective to the subjective, from the distant to the close-up, to deliberately mark the transition from dream to reality.

In order to try and gain a better understanding of this piece, we can wonder what part improvisation plays in this composition, if it is the result of automatic writing not controlled by reason? Of course, this question will remain without a firm and definitive answer. However, it is true that while the work seems to discourage our reason, it is a delight for our senses! The emotion is instinctively transmitted by the pictorial processes and not contained in the narrative of the painting. The random arrangement of patches of colour and the assertive silhouette of the subjects seem spontaneous, evoking the mechanical writing that André Breton said was the best way of letting the subconscious speak. The title Les Gens en colère d’un après-midi (Folk Irritated About an Afternoon) makes us wonder further about the surreal nature of this piece. Does its enigmatic wording reflect the fondness of artists such as Picabia or Magritte to give their compositions absurd names or completely detached from their subject, or is it just a clumsy translation of the title by an American who had only lived in France for a few years? At first glance, our composition confuses the mind with simultaneous, yet disjointed messages. On the one hand, the background featuring a ‘landscape’ of coloured spots evokes cheerfulness and lightness. On the other hand, the motifs consisting of an unintelligible tangle of elements of the human body, evoke chaos, dispute and heartbreak. The artist invites us here to a resolutely modern questioning of the power of line, space and form. Although there is a ten-year gap between them, it seems helpful to compare our painting to another important piece by this artist, La Danseuse de corde s’accompagne de ses ombres, 1916. Both pieces demonstrate the artist's contribution to conceptual and abstract art. Man Ray said that this painting is not the result of a preconceived idea, but rather a chance discovery. He composed it from irregularly shaped paper cuttings found on the ground, which had such visual power that he decided to paint a picture of them. The artist then arranges the motif of the dancer and the ropes that connect her to her shadows. The collage technique was highly appreciated by the Surrealists who saw it as allowing the exploitation of the chance meeting of two distinct realities. The juxtaposition of the coloured patches in our piece evokes this same visual force and provides an undeniable suggestive power. Both pieces use superimposition to create the illusion of relief. The freedom of the brushstrokes and the use of colour in these two paintings lay the foundations for a new representation of reality, allowing our piece to be approached in a resolutely abstract spirit. By exploring the physical properties of a painting in this way, the artist draws attention to the inherent two-dimensionality of paintings and establishes a different way of looking at a piece.

In a typically Surrealist way, Man Ray entices the viewer with a visual and conceptual shock. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that Les Gens en colère d’un après-midi was one of the key paintings exhibited at the 1936 British Surrealist exhibition at the Burlington Galleries. Through this monumental painting, Man Ray removes the absolute authority of the artist's hand in order to actively engage the audience in reading the work. The impact of light, colour and personal impressions are more important than how the model is captured in order to trigger emotion. This particularly modern and innovative approach is among the great innovations of modern art, calling into question pictorial conventions. By negating or at least questioning form, Man Ray played a key role in establishing a wider and freer pictorial reality.

| Künstler: | Man Ray (1890 - 1976) |

|---|---|

| Angewandte Technik: | Öl auf Leinwand |

| Kategorie des Auktionshauses: | Gemälde |

| Künstler: | Man Ray (1890 - 1976) |

|---|---|

| Angewandte Technik: | Öl auf Leinwand |

| Kategorie des Auktionshauses: | Gemälde |

| Adresse der Versteigerung |

CHRISTIE'S 9 Avenue Matignon 75008 Paris Frankreich | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vorschau |

| ||||||||||||||

| Telefon | +33 (0)1 40 76 85 85 | ||||||||||||||

| Fax | +33 (0)1 40 76 85 86 | ||||||||||||||

| Nutzungsbedingungen | Nutzungsbedingungen | ||||||||||||||

| Versand |

Postdienst Kurierdienst Selbstabholung | ||||||||||||||

| Zahlungsarten |

Banküberweisung | ||||||||||||||

| Geschäftszeiten | Geschäftszeiten

|