ID 1400150

Lot 213 | Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901)

Estimate value

€ 2 500 000 – 3 500 000

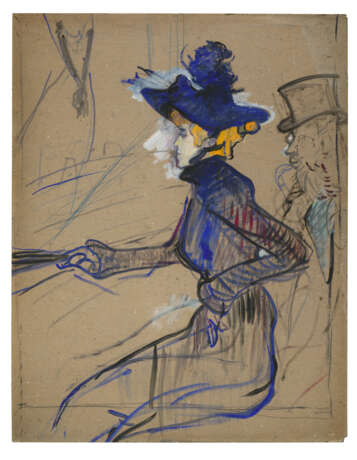

Jane Avril au Divan Japonais

inscrit 'JAPONAIS' (en haut à droite)

peinture à l’essence, crayon gras et graphite sur carton

82.5 x 64.5 cm.

Exécuté en 1892

inscribed 'JAPONAIS' (upper right)

peinture à l'essence, wax crayon and pencil on board

32 ½ x 25 3/8 in.

Executed in 1892

Provenance

George Viau, Paris.

Sirapé Sévadijan; sa vente, Me. Lair-Dubreil, Paris, 22 mars 1920, lot 23.

Jørgen Breder Stang, Norvège (acquis au cours de cette vente et jusqu'à au moins 1931).

Dr. Alfred Gold, Berlin et Paris.

Collection particulière, Paris (dans les années 1930).

Puis par descendance au propriétaire actuel.

Literature

G. Coquiot, H. de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paris, 1913, p. 171 (illustré).

M. Joyant, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Peintre, Paris, 1926, p. 274 (illustré, p. 187).

P. de Lapparent, Toulouse-Lautrec, Paris, 1927, p. 35.

P. Jamot, 'L'art français en Norvège, Galerie Nationale d'Oslo et collections particulières' in La Renaissance, New York et Paris, février 1929, No. 2, p. 100 (illustré, p. 93).

J. Galtier-Boissière, ‘Poil et Plume’, in Le Crapouillot, mai 1931, p. 38 (illustré).

‘Toulouse-Lautrec’, in Vogue, juin 1931, p. 59 (illustré).

E. Schaub Koch, Psychanalyse d’un peintre moderne, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paris, 1935, p. 203.

J. Lassaigne, Toulouse-Lautrec, Londres, 1939, p. 93 (illustré).

L. Borgese, Toulouse-Lautrec, 33 tavole, Milan, 1945 (illustré, pl. XVIII).

F. Jourdain, Toulouse-Lautrec, Lausanne et Paris, 1948, pl. 22 (illustré).

W. Kern, Toulouse-Lautrec, Berne, 1948, pl. 22 (illustré).

M. G. Dortu, Toulouse-Lautrec, Paris, 1952, p. 6.

E. Julien, Pour connaître Toulouse-Lautrec, 1953, p. 15 (illustré).

H. Focillon, Lautrec-Dessins, Lausanne et Paris, 1959, p. 22.

M. G. Dortu, Toulouse-Lautrec et son oeuvre, New York, 1971, vol. II, p. 248, no. P.420 (illustré, p. 249).

Exhibited

Berlin, Dr. Alfred Gold's Gallery, 35 Paintings selected from exhibitions, 1930 (illustré).

Paris, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Exposition H. de Toulouse Lautrec, avril-mai 1931, p. 29, no. 94 (illustré, pl. 4)

Further details

Cette œuvre est vendue en collaboration avec Madame Elisabeth Maréchaux Laurentin, Cabinet Maréchaux, à Paris.

This work is being sold in collaboration with Madame Elisabeth Maréchaux Laurentin, Cabinet Maréchaux, Paris.

Nous sommes en 1892, au Divan Japonais (fig. 1), un cabaret situé au 75 de la rue des Martyrs, sur les contreforts de la Butte Montmartre à Paris. A deux pas de là, est implanté le Cirque Fernando (Medrano) peint par Edgar Degas, que fréquentent Toulouse-Lautrec et bientôt … Pablo Picasso. Initialement nommé le Café de la chanson, le Divan Japonais est rebaptisé en 1886 par son nouveau propriétaire, Théophile Lefort, qui le redécore pour l’occasion de manière des plus surprenantes. Mais laissons John Grand-Carteret nous en faire la visite : « Dans cette fumisterie de haut goût qu’on a essayé de rendre plus piquante en confiant le service à des dames japonaises – encore plus chinoises que le reste – vous retrouverez le matériel du café parisien devenu par un subit changement de décor du japonisme d’occasion. Le billard se peint en bleu et rouge et on y colle des baguettes de bambou. Aux becs de gaz on ajoute des petites clochettes, aux murs on applique des grands panneaux de soie, comme il s’en trouve en certains magasins. Le comptoir reçoit également une teinte dans ce bleu et ce rouge qui sont particuliers aux peuples de l’Extrême-Orient. D’ancienne chaises Louis-Philippe, en acajou, sont badigeonnées avec une couche de vernis noir, le plafond se plaque en or avec des ornements de fantaisie, et tout est dit » (J. Grand-Carteret, Raphaël et Gambrinus, ou l’Art dans la brasserie, Paris, 1886, cité in F. Caradec et A. Weil, Le Café Concert, Paris, 1980, p. 88).

L’établissement est repris en 1889 par Jehan Sarrazin, un marchand d’olives venu de Nice, qui le transforme en un véritable café-concert, invitant les artistes à s’y produire. Il accueille lui-même dès l’entrée les nouveaux arrivants en plongeant une louche dans un baquet d’olives. En 1891, il débauche Yvette Guilbert (1867-1944) qui faisait alors les beaux jours du Moulin Rouge, pour lequel Toulouse-Lautrec réalise une affiche la même année. C’est la silhouette de la célèbre « diseuse » que nous découvrons à l’arrière-plan de notre tableau. Son visage est coupé par un cadrage serré, mais les gants, rehaussés de gris foncé, en confirment à eux seuls l’identité. Fréquentant assidument les cabarets et les cafés concerts du Paris de la « Belle Époque », Lautrec croque en réalité inlassablement ses artistes fétiches : La Goulue, certes, mais aussi la danseuse Jane Avril (1868-1943) (fig. 2), qui occupe ici le centre de la composition. Lautrec la portraiture, entre autres, dans Jane Avril dansant (1892) (Paris, musée d’Orsay) et dans Jane Avril entrant au Moulin Rouge (1892) (Londres, The Courtauld Institute of Art). Quant à Yvette Guilbert, Lautrec lui consacre en 1894 un album de seize lithographies, ainsi qu’une peinture Les Gants noirs (Albi, musée Toulouse-Lautrec), identifiant systématiquement l’artiste à cet accessoire, systématiquement porté depuis son engagement au Divan Japonais. A droite de notre tableau, c’est le profil de l’écrivain symboliste Édouard Dujardin (1861-1949) qui apparait. Fondateur de la Revue Wagnérienne (1885-1888) qui en défendait l’esthétique musicale, il devint, en 1886, le directeur de la Revue Indépendante, soutenant les avant-gardes artistiques. Dans sa Correspondance publiée en 1992, plusieurs lettres montrent que Lautrec fréquentait Dujardin, notamment en compagnie d’Alexandre Natanson. Dujardin passa toutefois à la postérité par son usage du monologue intérieur dont on trouve des échos chez James Joyce. (Herbert D. Schimmel, éd., Toulouse-Lautrec, Correspondance, Paris, 1992, p. 445). La légende veut qu’il ait été, en 1892, amoureux de Jane Avril.

Seules deux œuvres, préparatoires à l’affiche définitive (fig. 3), commandée par Édouard Fournier le nouveau propriétaire du lieu et parue en 1893, nous sont parvenues à ce jour : un grand dessin, au format de l’affiche définitive, ayant lui aussi appartenu à Georges Viau, puis à Robert von Hirsch (fig. 4), et notre tableau. Ce dernier est incontestablement antérieur au dessin « Viau-Hirsch », tant les variantes sont nombreuses : les musiciens, dont les crosses des contrebasses rappellent celles peintes par Edgar Degas dans L’Orchestre de l’Opéra (1869) (Paris, musée d’Orsay) sont absents de l’huile sur carton, tandis que la canne tenue par Édouard Dujardin, n’adopte pas encore la ligne serpentine qu’elle aura dans l’affiche définitive. Les contours de Jane Avril ainsi que la position de son bras gauche sont par ailleurs encore incertains. Mais Lautrec confère déjà une pose hiératique, d’une grande noblesse, à son modèle. Si le traitement de profil, sans volume, fait écho à certaines compositions d’Edgar Degas et de Georges Seurat, le dessin des bras et des mains suggère un mouvement visuellement dynamique. Tandis que la main droite tient un éventail fermé dont le motif s’achève hors du cadre, celle de gauche se replie vers le bas de la composition. Cette mise en page, au cadrage très photographique (notons le trait fin qui recadre la composition comme sur une planche-contact), anticipe sur les solutions imaginées bientôt par le cinéma ; entre les deux, le chainon manquant de cette révolution visuelles est, en 1892, les jeux d’ombre du Théâtre du Chat Noir que connaissait parfaitement Lautrec.

La manière avec laquelle le peintre fait usage de la couleur est révélatrice d’une autre dimension de notre tableau : tandis qu’il recouvre, dans l’affiche, Jane Avril d’une uniforme couleur noire, équilibrant ainsi sa composition autour d’un nombre réduit de teintes, il se laisse aller dans notre tableau à des bleus vifs, qui tantôt s’opposent à un jaune-orangé, tantôt sont rythmiquement rehaussés par un rouge soutenu. En ne recourant ici qu’aux trois couleurs primaires, qui se renforcent les unes les autres par contrastes chromatiques, Lautrec fait surgir Jane Avril du carton laissé en réserve, reléguant ainsi au second plan Yvette Guilbert et Édouard Dujardin. Notre tableau n’est toutefois en rien une simple recherche de teintes : celle-ci intervient généralement, chez Lautrec, lors de l’établissement du dessin définitif, voire sur des épreuves d’essais. Un cliché Vizzavona (fig. 5) du dessin « Viau-Hirsch », publié dans la revue L’Amour de l’Art en avril 1931, nous en dévoile les étapes. Nous découvrons sur cette photographie les traits de couleur de notre tableau, littéralement posés sur le grand dessin. Ce résultat a-t-il été obtenu grâce à un calque à ou un montage photographique ? Est-il le fruit d’une collaboration entre Lautrec et son ami le photographe Sescau ? La question demeure, « l’œuvre » reproduite en 1931 n’ayant à ce jour jamais été retrouvée. Il existe enfin une épreuve d’essais de l’affiche, rehaussée d’aquarelle, dans laquelle Jane Avril est traitée en un uniforme marron clair, tandis que l’orchestre, Édouard Dujardin ainsi qu’Yvette Guilbert, sont recouverts d’un gris-bleu pâle (Reproduite dans Toulouse-Lautrec et l’affiche, cat. exp., Paris, Fondation Dina Vierny-Musée Maillol, 2002, p. 40).

En réalité, les études en peinture sont souvent, chez Lautrec, l’occasion d’une approche beaucoup plus sensible du sujet. L’étape suivante, celle de la réalisation de l’estampe ou de l’affiche, sera celle du raisonnement, de la mise à distance. Pierre Bonnard, avec lequel il travaille en 1893, procèdera de la même manière tandis que Picasso, arrivé à Paris au début des années 1900, sera fasciné par l’éloquence de ces couleurs jetées sur un carton laissé « en réserve ». Lautrec synthétise ici une mise en page à la Degas, des couleurs chargées en émotion dont on retrouve l’écho dans certaines œuvres d’Edvard Munch, et des graphismes japonisant dont il était, avec son ami Pierre Bonnard, particulièrement friand. Certes, le dialogue entre les mediums participe chez Lautrec du processus même de création ; l’on ressent toutefois, dans la manière avec laquelle il sublime ici Jane Avril de couleurs puissantes, une communion sensible avec son modèle qui dépasse la simple recherche graphique. Il est à l’évidence fasciné par cette artiste. Dans ses yeux admiratifs, la danseuse acquiert le statut d’une dame du grand monde.

La dimension iconique de notre tableau explique sans doute son pedigree tout à fait exceptionnel ; il appartint en premier lieu à Georges Viau (1855-1939), qui non seulement possédait une l’étude déjà mentionnée pour le Divan Japonais (fig. 4), mais aussi deux grands panneaux, La Danse au Moulin Rouge et La Danse Mauresque (Paris, musée d’Orsay), peints par Lautrec pour la Baraque de la Goulue en 1895. Ses tableaux et ses dessins de Lautrec avaient d’ailleurs été prêtés, comme le mentionne le catalogue de sa vente en 1907, au Salon d’Automne en 1904 (Catalogue des Tableaux modernes Pastels et Aquarelles […] composant la Collection de M. Georges Viau, Paris, Galeries Durand-Ruel, 4 mars 1907). Bien que l’on ne puisse trancher de façon définitive, l’on imagine mal Viau prêter au Salon d’Automne sa seule version dessinée du Divan Japonais au détriment de notre tableau, bien plus spectaculaire. Sa collection rassemblait par ailleurs des œuvres de premier ordre, allant du Romantisme à l’École de Pont-Aven, de Daumier à Gauguin, en passant par Cézanne, Degas, Monet, et même un Van Gogh. Notre tableau passe ensuite chez Sirapé Sevadjian (fig. 6), dont la collection comprenait des Cézanne, des Degas, des Marie Laurencin et pas moins de quinze Toulouse-Lautrec ! Parmi ceux-ci, l’extraordinaire Dressage des nouvelles par Valentin le Désossé (Moulin Rouge) (1889-1890) (Philadelphie, Philadelphia Museum of Art) et la très importante Étude pour « La Grande Loge » (1896), préparatoire à cette autre œuvre graphique emblématique de Lautrec. Notre tableau est ensuite acquis par le norvégien Jørgen Breder Stang (1874-1950) (fig. 7). Héritier de l’entreprise forestière de son père qu’il continuera de développer, il se spécialise dans le transport maritime, secteur devenu crucial lors de la 1ère Guerre Mondiale. Dans sa demeure d’Oslo, il rassemble une collection devenue mythique, tant par sa qualité que par son histoire : citons La Mousmé (1888) (Washington, The National Gallery) de Vincent Van Gogh, Les Joueurs de cartes (1892-1895) (Londres, The Courtauld Institute) de Paul Cézanne, D’où venons-nous ? Que sommes-nous ? Où allons-nous ? (1897-1898) (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts) de Paul Gauguin, etc. Tous ces chefs d’œuvre de classe mondiale, ayant été refusés par la ville d’Oslo en paiement d’une dette fiscale, furent dispersés, et pour partie rachetés dans les années 1930 par Alfred Gold (1874-1958). Journaliste autrichien (il travaille comme éditeur au journal Die Zeit fondé par Hermann Bahr), critique de théâtre, passionné de musique (Arnold Schönberg s’inspire de certains de ses textes), collectionneur mais aussi marchand, Gold est un des plus brillants esprits de la Vienne fin-de-siècle. Nombre des tableaux qu’il posséda sont aujourd’hui accrochés aux cimaises des plus grands musées, ainsi le Paysage algérien (1881) (Paris, musée d’Orsay) de Renoir, venu lui aussi de chez Stang, ou encore La Tamise devant Westminster (1871) (Londres, The National Gallery) de Monet. Partageant son temps entre l’Allemagne et la France (il expose chez Georges Petit à Paris), Gold exposa notre tableau en 1930 dans sa galerie à Berlin. En 1931, notre tableau participe à la rétrospective organisée par le musée des Arts Décoratifs à Paris. L’importance de cette exposition suscite plusieurs publications rendant hommage à Lautrec, notamment un « Numéro Spécial » de la revue L’Amour de l’Art consacré à l’artiste, comprenant entre autres des textes de Tristan Bernard, Romain Coolus et Claude Roger-Marx, et même des anecdotes inédites confiées par Édouard Vuillard lui-même.

Les œuvres de Lautrec ont tellement imprégné nos imaginaires collectifs qu’elles semblent presque évidentes. Il suffit toutefois de jeter un œil sur certaines affiches contemporaines (fig. 8) pour le même Divan Japonais, pour mesurer l’abîme esthétique qui les sépare. Lautrec fit toutefois plus que cela. Grâce à ses images, des jeunes femmes jusqu’alors inconnues deviennent célèbres en un instant. Jane Avril confie à ce propos dans ses Mémoires, « Il est plus que certain qu’à lui je dois la célébrité dont j’ai joui, dès sa première affiche de moi. » (Jane Avril, Mes Mémoires, Paris, 2005, p. 61). Plus encore, en faisant d’un profil, d’une pose, d’un accessoire vestimentaire, les symboles et les signes visuels même de telle ou telle artiste, il se situe comme le précurseur incontestable des grands affichistes du XXe siècle, … mais aussi d’Andy Warhol pour sa capacité à ériger l’anecdote en une icône mythique.

It is 1892, and we are at the Divan Japonais (fig. 1), a cabaret located at 75 rue des Martyrs, on the slopes of Montmartre in Paris. Just a stone’s throw away stands the Cirque Fernando (later Medrano), painted by Edgar Degas and frequented by Toulouse-Lautrec and soon… Pablo Picasso. Initially named the “Café de la Chanson”, the Divan Japonais was renamed in 1886 by its new owner, Théophile Lefort, who redecorated it in the most surprising fashion. But let us allow John Grand-Carteret to take us on a tour: “In this high-taste humbug, made even more piquant by entrusting the service to Japanese ladies—who appear even more Chinese than the rest—you will find the usual furnishings of a Parisian café, transformed through a sudden change of decor into a makeshift Japonisme. The billiard table is painted blue and red and adorned with bamboo sticks. Small bells are added to the gas lamps, and large silk panels, like those found in certain stores, are applied to the walls. The counter is also tinted in the same blue and red hues characteristic of the Far East. Old Louis-Philippe mahogany chairs are coated with a layer of black varnish, the ceiling is covered in gold leaf and decorated with fanciful ornaments, and that’s it” (J. Grand-Carteret, Raphaël et Gambrinus, ou l’Art dans la brasserie, Paris, 1886, cité in F. Caradec et A. Weil, Le Café Concert, Paris, 1980, p. 88).

The establishment was taken over in 1889 by Jehan Sarrazin, an olive merchant from Nice, who transformed it into a true café-concert, inviting artists to perform there. He personally welcomed guests at the entrance, dipping a ladle into a tub of olives. In 1891, he lured away Yvette Guilbert (1867-1944), who had been a major star at the Moulin Rouge, for which Toulouse-Lautrec had created a poster that same year. In the background of our painting, we recognize the silhouette of the famous “diseuse.” Her face is cropped by a tight framing, but her gloves, highlighted in dark gray, alone confirm her identity. A regular at the cabarets and café-concerts of La Belle Époque Paris, Lautrec tirelessly sketched his favorite performers: La Goulue, of course, but also the dancer Jane Avril (1868-1943) (fig. 2), who occupies the center of this composition. Lautrec portrayed her in works such as Jane Avril dansant (1892) (Paris, Musée d’Orsay) and Jane Avril entrant au Moulin Rouge (1892) (London, The Courtauld Institute of Art). As for Yvette Guilbert, Lautrec dedicated a series of sixteen lithographs to her in 1894, as well as a painting, Les Gants noirs (Albi, Musée Toulouse-Lautrec), systematically linking the artist with this accessory, which she had invariably worn since her debut at the Divan Japonais. To the right of our painting appears the profile of the symbolist writer Édouard Dujardin (1861-1949). Founder of La Revue Wagnérienne (1885-1888), which championed Wagner’s musical aesthetics, he became director of La Revue Indépendante in 1886, supporting avant-garde artists. His Correspondence, published in 1992, includes several letters indicating that Lautrec socialized with Dujardin, often in the company of Alexandre Natanson. (Herbert D. Schimmel, éd., Toulouse-Lautrec, Correspondance, Paris, 1992, p. 445). Dujardin, however, earned his place in literary history through his pioneering use of the interior monologue, echoes of which are found in the writings of James Joyce. Legend has it that in 1892, he was in love with Jane Avril.

Only two preparatory works for the final poster (fig. 3), commissioned by Édouard Fournier, the new owner of the venue, and published in 1893, are known to have survived: a large drawing in the same format as the final poster, which also belonged to Georges Viau and later to Robert von Hirsch (fig. 4), and our painting. The latter is undoubtedly earlier than the Viau-Hirsch drawing, given the many differences: the musicians, whose double bass scrolls recall those painted by Edgar Degas in L’Orchestre de l’Opéra (1869) (Paris, Musée d’Orsay), are absent from the oil on cardboard, while the cane held by Édouard Dujardin has not yet assumed the sinuous shape it would take in the final poster. Jane Avril’s outline and the position of her left arm remain undefined. However, Lautrec already confers upon his model a hieratic pose of great nobility. While the profile treatment, devoid of volume, echoes compositions by Edgar Degas and Georges Seurat, the rendering of the arms and hands suggests a visually dynamic movement. The right hand holds a closed fan whose motif extends beyond the frame, while the left hand folds downward toward the bottom of the composition. This layout, with its highly photographic framing (note the fine line that crops the composition, reminiscent of a contact sheet), anticipates visual effects soon to be explored by cinema; between the two, the missing link in this visual revolution was, in 1892, the shadow plays performed at the Théâtre du Chat Noir, with which Lautrec was thoroughly familiar.

The painter’s use of color reveals another dimension of our painting. While in the final poster he depicts Jane Avril entirely in black, thereby balancing his composition around a reduced range of colours, in this painting he allows himself vibrant blues, at times contrasting with a yellow-orange, and rhythmically punctuated by deep reds. By restricting himself exclusively to the three primary colors, which reinforce one another through their chromatic contrasts, Lautrec brings Jane Avril vividly forth from the untouched cardboard, pushing Yvette Guilbert and Édouard Dujardin into the background. Our painting, however, is far from being simply a color study: Lautrec typically explored color variations at the stage of the final drawing or even on trial impressions. A Vizzavona photograph (fig. 5) of the Viau-Hirsch drawing, published in the magazine L’Amour de l’Art in April 1931, reveals these successive stages. In this photograph, we distinctly see the color strokes of our painting literally transferred onto the large drawing. Was this result achieved through tracing paper or a photographic montage? Could it even be the outcome of a collaboration between Lautrec and his friend, the photographer Sescau? The question remains unanswered, as « the work » reproduced in 1931 has never been located to this day. Additionally, there is also known to be a trial proof of the poster, enhanced with watercolor, in which Jane Avril is uniformly depicted in a light brown, while the orchestra, Édouard Dujardin, and Yvette Guilbert are covered with a pale blue-gray (Reproduced in Toulouse-Lautrec et l’affiche, cat. exp., Paris, Fondation Dina Vierny-Musée Maillol, 2002, p. 40).

In truth, Lautrec’s painted studies often allow for a more sensitive approach to the subject. The next step—the creation of a print or poster—demands reasoning and critical distance. Pierre Bonnard, with whom Lautrec worked in 1893, adopted a similar method, while Picasso, upon his arrival in Paris in the early 1900s, would be fascinated by the expressiveness of these colors freely applied onto a bare surface. Here, Lautrec brilliantly combines Degas’s compositional style, emotionally charged colors reminiscent of Edvard Munch, and the japonisme-infused graphic elements he particularly favored, alongside his friend Pierre Bonnard. Certainly, the interplay between mediums was integral to Lautrec’s creative process. Yet, the manner in which he elevates Jane Avril with bold, vibrant colors reveals a profound connection with his model that transcends mere graphic experimentation. It is clear that he was captivated by this artist. In his admiring gaze, the dancer acquires the dignity of a society lady.

The iconic status of our painting undoubtedly explains its exceptional provenance. It first belonged to Georges Viau (1855-1939), who not only owned the previously mentioned study for the Divan Japonais (fig. 4), but also two large panels, La Danse au Moulin Rouge and La Danse Mauresque (Paris, Musée d'Orsay), painted by Lautrec for Baraque de la Goulue both in 1895. Lautrec's paintings and drawings from his collection had, moreover, been lent, as the 1907 sale catalogue mentions, to the Salon d'Automne in 1904 (Catalogue des Tableaux modernes Pastels et Aquarelles […] composant la Collection de M. Georges Viau, Paris, Galeries Durand-Ruel, 4 mars 1907). Although it is impossible to state definitely, it seems unlikely that Viau would have loaned his drawn version of Divan Japonais alone, instead of our painting, which is far more spectacular. His collection also included first-rate works, ranging from Romanticism to the Pont-Aven School, from Daumier to Gauguin, Cézanne, Degas, Monet, and even a Van Gogh.

Our painting subsequently passed to Sirapé Sevadjian (fig. 6), whose collection featured Cézannes, Degas, works by Marie Laurencin, and no fewer than fifteen Toulouse-Lautrecs ! Among these was the extraordinary Dressage des nouvelles par Valentin le Désossé (Moulin Rouge) (1889-1890) (Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art) and the highly important Study for La Grande Loge (1896), preparatory for another of Lautrec’s iconic graphic works. The painting was then acquired by the Norwegian collector Jørgen Breder Stang (1874-1950) (fig. 7). The heir to his father's forestry business, which he continued to develop, Stang specialized in maritime transport, a sector that became crucial during World War I. In his Oslo residence, he assembled a collection that became legendary both for its quality and its remarkable history. Among its masterpieces were La Mousmé (1888) (Washington, The National Gallery) by Vincent Van Gogh, Les Joueurs de cartes (1892-1895) (London, The Courtauld Institute) by Paul Cézanne, and D’où venons-nous ? Que sommes-nous ? Où allons-nous ? (1897-1898) (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts) by Paul Gauguin. All these world-class masterpieces, rejected by the city of Oslo as payment for a tax debt, were dispersed and partially acquired in the 1930s by Alfred Gold (1874-1958). Gold, an Austrian journalist (he served as editor at Die Zeit, founded by Hermann Bahr), theater critic, music enthusiast (Arnold Schönberg drew inspiration from some of his texts), collector, and dealer, was one of Vienna's most brilliant minds at the turn of the century. Many of the paintings he owned now adorn the walls of major museums, such as Renoir's Paysage algérien (1881) (Paris, Musée d'Orsay), also acquired from Stang, and Monet's La Tamise devant Westminster (1871) (London, The National Gallery). Splitting his time between Germany and France (he exhibited at Georges Petit in Paris), Gold exhibited our painting in 1930 in his Berlin gallery. In 1931, our painting featured prominently in the retrospective organized by the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. The importance of this exhibition generated numerous publications paying tribute to Lautrec, notably a "Special Issue" of the magazine L'Amour de l'Art dedicated to the artist, which included texts by Tristan Bernard, Romain Coolus and Claude Roger-Marx, as well as unpublished anecdotes shared by Édouard Vuillard himself.

Lautrec's works have so profoundly permeated our collective imagination that they almost seem self-evident. Yet, one only needs to glance at certain contemporary posters (fig. 8) for the same Divan Japonais to measure the aesthetic gulf that separates them. Lautrec did far more than that. Thanks to his images, young women who were previously unknown became instantly famous. Jane Avril herself confessed in her memoirs, "It is beyond doubt that I owe to him the fame I enjoyed, from his very first poster of me." (Jane Avril, Mes Mémoires, Paris, 2005, p. 61). Moreover, by making a profile, a pose, or a garment accessory into symbols and visual signatures of specific artists, Lautrec positioned himself as the indisputable precursor of the great poster artists of the twentieth century… and even anticipated Andy Warhol in his ability to transform anecdotal detail into mythic icons.

| Artist: | Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864 - 1901) |

|---|---|

| Applied technique: | Oil, Painted |

| Auction house category: | Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings, Paintings |

| Artist: | Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864 - 1901) |

|---|---|

| Applied technique: | Oil, Painted |

| Auction house category: | Paintings, Watercolors, Drawings, Paintings |

| Address of auction |

CHRISTIE'S 9 Avenue Matignon 75008 Paris France | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preview |

| ||||||||||||||

| Phone | +33 (0)1 40 76 85 85 | ||||||||||||||

| Fax | +33 (0)1 40 76 85 86 | ||||||||||||||

| Conditions of purchase | Conditions of purchase | ||||||||||||||

| Shipping |

Postal service Courier service pickup by yourself | ||||||||||||||

| Payment methods |

Wire Transfer | ||||||||||||||

| Business hours | Business hours

|