ID 832054

Lot 15 | Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)

Estimate value

€ 2 000 000 – 3 000 000

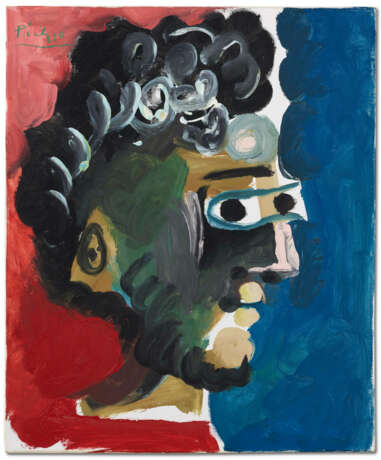

Tête d'homme de profil II

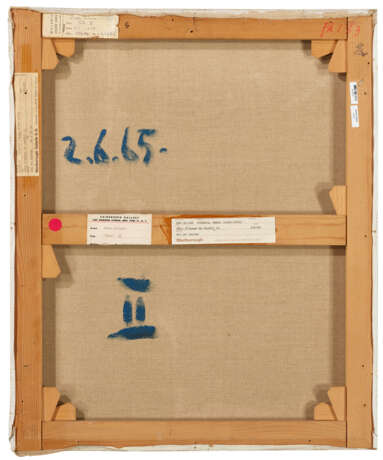

signé 'Picasso' (en haut à gauche); daté et numéroté '2.6.65. II' (au revers)

huile sur toile

65.1 x 54.2 cm.

Peint le 2 juin 1965

signed 'Picasso' (upper left); dated and numbered ‘2.6.65. II’ (on the reverse)

oil on canvas

25 5/8 x 21 3/8 in.

Painted on 2 June 1965

Provenance

Galerie Louise Leiris, Paris.

Saidenberg Gallery, New York.

Marlborough Fine Art, New York.

Sheldon A. Vermes, États-Unis; vente, Sotheby's, New York, 12 novembre 1987, lot 455.

Acquis au cours de cette vente par le propriétaire actuel.

Literature

C. Zervos, Pablo Picasso, Catalogue raisonne´, Œuvres de 1965 a' 1967, Paris, 1972, vol. 25, no. 149 (illustré, pl. 84).

Special notice

On occasion, Christie's has a direct financial interest in lots consigned for sale which may include guaranteeing a minimum price or making an advance to the consignor that is secured solely by consigned property. This is such a lot. This indicates both in cases where Christie's holds the financial interest on its own, and in cases where Christie's has financed all or a part of such interest through a third party. Such third parties generally benefit financially if a guaranteed lot is sold successfully and may incur a loss if the sale is not successful.

Artist's Resale Right ("droit de Suite").

If the Artist's Resale Right Regulations 2006 apply to this lot, the buyer also agrees to pay us an amount equal to the resale royalty provided for in those Regulations, and we undertake to the buyer to pay such amount to the artist's collection agent.

ƒ: In addition to the regular Buyer’s premium, a commission of 5.5%

inclusive of VAT of the hammer price will be charged to the buyer.

It will be refunded to the Buyer upon proof of export of the lot

outside the European Union within the legal time limit.

(Please refer to section VAT refunds)

Post lot text

Picasso a peint au début de sa carrière de nombreux portraits d'amis et de confrères de sexe masculin. Il reste, évidemment, bien plus célèbre pour avoir ensuite représenté, de manière presque compulsive, les femmes qui ont partagé sa vie – d'abord Fernande Olivier, puis sa première épouse Olga Khokhlova suivie de Marie-Thérèse Walter, Dora Maar, Françoise Gilot et enfin Jacqueline Roque, dont il est devenu l'amant en 1954 et l'époux en 1961. Si quelques hommes, principalement des compagnons de lettres, sont apparus de temps à autre dans ses dessins après le milieu des années 1920, Picasso ne leur a jamais consacré de tableaux. Pendant de longues années, l'artiste n'a par ailleurs réalisé que de très rares dessins de sujets masculins anonymes. Or dans son grand âge, des têtes, torses et silhouettes d'hommes et de garçons envahissent soudainement ses travaux, tous supports confondus. Conçu le 2 juin 1965, Tête d'homme de profil II en constitue un exemple particulièrement éloquent, de par la verve extraordinaire de ses couleurs et de sa manière.

La série que Picasso initie en 1963 sur le thème de l'artiste avec son modèle emplit son œuvre d'une forte charge sensuelle, qui galvanisera l'ensemble de sa production tardive. Alter-ego de Picasso, le peintre qui apparaît dans ces scènes contemple le plus souvent son sujet féminin avec insistance et avidité ; le modèle, pour sa part, affiche invariablement certains signes distinctifs de Jacqueline, sa dernière épouse. À cette époque, celle-ci devient pour Picasso un « éternel féminin » de chair et d'os, la muse dévouée et débordante de vie dont il dispose au quotidien. Aussi se plaît-il à la peindre nue, dans des scènes sous-tendues par de subtils jeux de désir et de séduction, de réticence et d'abandon charnel. S'en dégage un érotisme souvent plein de tendresse et d'humour, qui teinte cette rivalité des sexes d'un esprit courtois et bon enfant. Objet perpétuel de sa convoitise, Jacqueline est alors l'une des constantes de l'existence de Picasso. Elle finit par incarner l'essence même de la beauté et de l'amour, les deux fils rouges de son art. Or dans l'atelier, ce sont l'inconstance et la versatilité qui priment : durant ses dernières années, le travail de Picasso brille par une diversité qui se reflète, notamment, dans la multitude de personnages sur lesquels il projette sa présence masculine.

Le thème de l'artiste et son modèle habite son œuvre depuis moins d'un an lorsque Picasso décide de se tourner vers des personnages masculins radicalement différents : la figure du peintre dans son atelier cède bientôt le pas à d'autres archétypes, généralement des travailleurs bien bâtis qui exercent des métiers de plein air. Le jeune homme aux cheveux bouclés que Picasso représente dans Tête d’homme de profil II compte parmi ces mâles vaillants et virils qui assaillent ses peintures et dessins à partir de 1964, au point parfois de surpasser en nombre ses sujets féminins.

Ni adolescent imberbe, ni tout à fait encore dans la fleur de l'âge, cet individu énigmatique paraît plein d'aplomb et d'allant. L'impression de vigueur est renforcée par le bleu et le rouge intenses de l'arrière-plan, qui tranchent avec l’ocre et le vert de ce visage couronné par les volutes dynamiques de la chevelure. Cet homme sans âge évoque le genre de travailleur que Jacqueline et Picasso auraient pu croiser à Cannes et ses environs au milieu des années 1960 – quelqu'un qui vit de la mer, un marin, docker, pêcheur ou poissonnier peut-être. À moins qu'il ne s'agisse d'un personnage inspiré de Maurice Bresnu, que Picasso emploie comme chauffeur début 1965 : « Dès lors, note John Richardson, des hommes Bresnu-esques à la barbe frisée et à la toison brune firent des apparitions de plus en plus fréquentes dans l'imagerie de l'artiste ».

Cet individu robuste et barbu s'inscrit à bien des égards dans une longue tradition artistique du bassin méditerranéen qui remonte à l'Antiquité. Les traits du visage pourraient évoquer ceux d'un personnage mythologique ou d'un commerçant tel qu'on en trouve dans l'art grec ancien, ou bien le profil d'une statue classique de dieu ou de noble romain. Dans une certaine mesure, le faciès rappelle aussi les figures de saints ou les représentations stylisées du Christ de l'art byzantin. Quelle qu'ait été sa source d'inspiration, lorsqu'il a peint ce portrait en 1965, Picasso aurait aisément pu s'identifier à ces divers types masculins : au brave aventurier de la mer, à l'aristocrate tout-puissant, au demi-dieu de l'Olympe ou même au saint personnage de la Bible. Durant les dix dernières années de sa vie, l'artiste est en effet – et plus que jamais – mondialement reconnu comme l'un des monstres sacrés de l'art du XXe siècle. Son œuvre connaît un succès sans précédent que Cecil Beaton entérine dans un article retentissant écrit à la suite d'une visite chez l'artiste au printemps 1965 à Notre-Dame-de-Vie, sa demeure à Mougins. Paru le 15 septembre 1965 dans Vogue, ‘Golden Picasso’ dévoile notamment certains des clichés désormais célébrissimes que Beaton a pris du peintre.

Cette Tête d’homme de profil II affiche une mirada fuerte, ce regard puissant et ténébreux qui faisait la renommée de Picasso. Une expressivité extraordinaire qui semble bien indiquer que ce protagoniste incarne, d’une manière ou d’une autre, la personne de l'Andalou ; dans d’autres œuvres, Picasso habille d’ailleurs volontiers ce genre de figure de sa légendaire marinière. Les yeux noirs perçants renvoient aussi, une fois de plus, à l'art antique. Le regard percutant semble notamment faire allusion aux portraits funéraires du Fayoum, peints deux mille ans plus tôt en Égypte gréco-romaine, et étudiés de près au Louvre par de nombreux artistes modernes, dont Picasso. Par ailleurs, le jour même où il conçoit la présente toile, dont le personnage se tourne vers la droite, l'Espagnol peint aussi Tête de femme I, un profil féminin qui regarde vers la gauche, et qui représente manifestement son épouse, Jacqueline.

La plupart des têtes et bustes d’hommes que Picasso exécute durant cette période affichent les mêmes caractéristiques physiques : une physionomie constituée d’épais coups de pinceaux qui se dispersent, se superposent et s’entrecroisent, afin de suggérer un nez, une ombre sur une joue, des yeux grand ouverts ou un sourcil levé. Or dans Tête d’homme de profil II, le peintre opte pour un expressionnisme plus figuratif, marqué par des touches d’ombres et de couleurs appliquées d’un geste vif et démonstratif - loin de l’approche plus sommaire qui domine sa maturité. En ce sens, cette toile marque une transition entre les ouvriers puissants et barbus du milieu des années 1960, traités de manière laconique, presque abstraite, et les hidalgos distingués, barbichette et moustache pointue, qui vont conquérir à partir de 1967 les ultimes toiles de Picasso. Ces cavaliers et mousquetaires aux costumes élégants qui deviennent bientôt ses sujets favoris dérivent tant du Siglo de Oro espagnol que de la peinture baroque flamande de Rembrandt, Rubens ou Hals. Avant de se révéler au monde – et de lui tirer sa révérence – dans ces costumes d’époque fantasques, Picasso se peint ainsi de manière plus neutre, libre de tout attribut superflu, dans ce portrait de 1965 d’une vivacité saisissante, où toute son attention se porte sur l’expression et les traits du visage : un « Picasso d’or », pur et simple, pour reprendre la formule de Cecil Beaton.

Picasso painted numerous portraits of male friends and colleagues during his early career. He is, of course, far more famous for later having obsessively depicted the notable women in his life–Fernande Olivier, his first wife Olga Khokhlova, Marie-Thérèse Walter, Dora Maar, Françoise Gilot and finally Jacqueline Roque, his lover since 1954, whom he married in 1961. While he occasionally drew portraits of male literary friends and a few other men after the mid-1920s, he never painted them, and only rarely depicted anonymous male subjects. However, the heads, busts and figures of men and boys suddenly abound among his late works in all media, of which the present portrait, Tête d’homme de profil II, painted on 2 June 1965, is a particularly striking example, through its presence and vibrancy in terms of color and brushstrokes.

With the emergence in 1963 of his artist and model series, Picasso had forged the highly charged sexual dynamic that would galvanize the full compass of his late work. The painter, as a surrogate for Picasso himself, typically gazes intently upon his female subject; the model, for her part, always embodies some aspect of the artist’s wife Jacqueline. She became his ever-attendant muse, l’éternel féminin whom he daily experienced in her ever vital, flesh-and-blood presence, revealing her in his paintings always nude, in pictorial scenarios that suggest sophisticated games of desire and seduction, coyness and consent, in which an appealing air of often humorous eroticism betoken a civil and good-natured contest of the sexes. As the perennial object of his desire, Jacqueline was a constant in his life, the very essence of beauty and love as perpetual ideals to which he did homage in his art. Picasso, on the other hand, assumed a more mercurial role in his pursuit of the creative life, taking on a diversely protean nature as the character types into which he projected his male presence.

Picasso had been painting his artist and model series for less than a year when he transformed his chosen painted persona from the artist absorbed in his studio work into other noticeably different male types, usually workingmen who labored outdoors, in the full glare and open air of the outside world. The curly haired young man Picasso has depicted in this Tête d’homme de profil II is one of the capably active, virile men who started appearing in droves among Picasso’s paintings and drawings since the spring of 1964, occasionally outnumbering his female subjects at times.

This fellow is of an indeterminate age—he is neither a beardless youth, nor quite yet a much older, seasoned and all-too-wise man of the world. He appears, in any case, ready and eager for the task at hand. His energy is further invigorated by the deep red and blue background contrasting with his green and ochre face, crowned with the dynamic twirls of his curls. He is one such type that Picasso and Jaqueline might have encountered in Cannes and its environs during the mid-1960s, someone who likely made his livelihood from the Mediterranean, as an able-bodied sailor, a dock worker, a fisherman or fishmonger. Or, as John Richardson has noted, in early 1965 Picasso employed Maurice Bresnu as his driver—“Henceforth Bresnu-like men with curly beards and blobs of dark hair would appear ever more frequently in the artist’s imagery.”

This strong bearded fellow is in the classic Mediterranean mold, of a type as old as antiquity. His features recall that of a Greek mythological character or a real Greek trader; of an Antique sculpture of a Roman God or noble, and they are also reminiscent, to some extent, of male saints and even the stylized figure of Christ represented in Byzantine icons. Whatever the source of inspiration, Picasso could easily relate to all these different characters, whether a heroic kind of man venturing the sea, a dominant aristocrat, a superior being or even a holy figure, and even more so by 1965, when he painted this portrait. Indeed, during the last decade of his life, he reaffirmed his international recognition as one of the leading fathers of 20th century art, and encountered unprecedented success, which Cecil Beaton epitomized in the famous article he wrote for the 15th September 1965 Vogue issue, entitled ‘Golden Picasso’. Beaton visited Picasso in his villa Notre-Dame-de-Vie in Mougins in Spring 1965, and took his world-renowned shots of Picasso – that have today immortalized the great master - some of which were to be published alongside his article.

This Tête d’homme de profil II shows off the mirada fuerte, the strong gaze, for which Picasso was famous, an indication that the artist has in some way projected himself into this character, as a surrogate or an alter ego; elsewhere the artist attired these men in the striped fisherman’s jersey he liked to wear at home. These powerful eyes are one of the most striking and beguiling features seen in the ancient portraiture to which Picasso here has likely alluded, the mummy portraits painted two millennia ago in the Fayum region of Graeco-Roman Egypt, which he and other modern painters had studied in the Louvre. On the same day he painted the present work, Picasso also produced Tête de femme I, showing a woman’s profile turning towards the left, as opposed to the right as in Tête d’homme de profil II, which clearly represents his muse and partner at that time, Jacqueline.

For most of these male heads and busts Picasso devised a particular set of facial traits, a physiognomy comprised of swerving, overlaid and intersecting strokes of a loaded brush, to suggest the shape of the nose, the shadow on a cheek, the wide open eyes and raised brow. Yet in Tête d’homme de profil II, Picasso opts for a more figurative expressionism defined by rich, gestural brushstrokes of color and shadows, rather than the more summary means usually found in his very late style at the end of the 1960s. In some ways, the present painting stands as a transition between the almost abstract and suggestive brawny, unshaven workingmen of the mid-1960s and the elegantly pointed moustaches and goatees of Picasso’s newly favored personae that appeared in his oeuvre in 1967, his lavishly dressed cavaliers and musketeers, that he lifted from the Spanish Siglo de Oro and the northern golden Baroque era of Rembrandt, Rubens, and Hals. Therefore, before presenting himself to the world during the final years of his life in this guise of mock-historical role-playing, Picasso painted himself in this extraordinarily lively 1965 portrait, devoid of any attribute or costume, focusing solely on his facial expression and features: he was, in Cecil Beaton’s words, the ‘Golden Picasso’.

| Artist: | Pablo Picasso (1881 - 1973) |

|---|---|

| Applied technique: | Oil on canvas |

| Auction house category: | Paintings |

| Artist: | Pablo Picasso (1881 - 1973) |

|---|---|

| Applied technique: | Oil on canvas |

| Auction house category: | Paintings |

| Address of auction |

CHRISTIE'S 8 King Street, St. James's SW1Y 6QT London United Kingdom | |

|---|---|---|

| Preview |

| |

| Phone | +44 (0)20 7839 9060 | |

| Buyer Premium | see on Website | |

| Conditions of purchase | Conditions of purchase |