ID 929385

Lot 5 | René Magritte (1898-1967)

Estimate value

€ 3 000 000 – 5 000 000

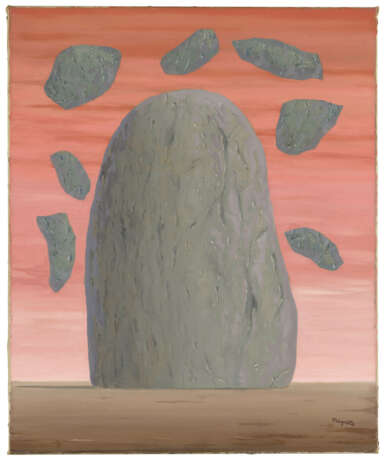

Les Grains de beauté

signé 'Magritte' (en bas à droite); inscrit '"LES GRAINS DE BEAUTÉ"' (au revers)

huile sur toile

55.3 x 45.6 cm.

Peint vers 1965

signed 'Magritte' (lower right); inscribed '"LES GRAINS DE BEAUTÉ"' (on the reverse)

oil on canvas

21 3/4 x 17 7/8 in.

Painted circa 1965

Provenance

Galleria Schwarz, Milan (vers 1969).

Davlyn Gallery, New York (acquis auprès de celle-ci entre 1971 et 1974).

Michelle Rosenfeld Fine Art, New Jersey (vers 1990).

Acquis par le propriétaire actuel en 2010.

Literature

D. Sylvester, éd., René Magritte, Catalogue raisonné, Oil paintings, Objects and Bronzes, 1949-1967, Londres, 1993, vol. III, p. 419, no. 1025 (illustré).

Exhibited

Hannovre, Kestner-Gesellschaft et Zurich, Kunsthaus, René Magritte, mai-juin 1969, p. 76, no. 75 (illustré, p. 155).

New York, Davlyn Gallery, Magritte, Paintings, Gouaches, Collages, novembre 1974 -janvier 1975, no. 18 (illustré; daté '1966').

Special notice

Artist's Resale Right ("droit de Suite").

If the Artist's Resale Right Regulations 2006 apply to this lot, the buyer also agrees to pay us an amount equal to the resale royalty provided for in those Regulations, and we undertake to the buyer to pay such amount to the artist's collection agent.

ƒ: In addition to the regular Buyer’s premium, a commission of 5.5%

inclusive of VAT of the hammer price will be charged to the buyer.

It will be refunded to the Buyer upon proof of export of the lot

outside the European Union within the legal time limit.

(Please refer to section VAT refunds)

Post lot text

« Mes tableaux sont valables, à mes yeux, si les objets qu’ils représentent résistent à des interprétations par symboles ou par d’autres explications. »

René Magritte.

L’artiste René Magritte pose dans cette phrase-manifeste une exigence intellectuelle et artistique de taille et dont la présente œuvre, Les Grains de Beauté, peinte vers 1965, est l’une des meilleures illustrations.

Chez Magritte certaines œuvres semblent hermétiquement fermées sur elles-mêmes, résistantes à toute tentative rationnelle d’analyse. Singuliers, autonomes et autosuffisants, les tableaux de Magritte paraissent ne devoir susciter ni parallèle ni filiation car leur essence est de susciter le questionnement du réel et de représenter l’étrange dans ses plus simples manifestations.

Tout au long de sa carrière, l’artiste met en scène l’énigmatique en posant dans ses toiles des rapports incongrus entre les objets ou entre les qualités principales des éléments de la composition. L’artiste se joue des rapports de proportion, des lois de la pesanteur ou de la gravité et des identités attribués par le consensus aux objets afin de les dépourvoir de leur valeur utilitaire. Cette démarche permet un nouveau regard sur la chose et élargit l’espace de vie des objets usuels. En représentant l’inexplicable et l’inexpliqué, Magritte formule le souhait de poser le mystère en pleine lumière.

Cette interrogation sur la nature des choses et le rapport entre le mot et la représentation apparait très tôt dans la peinture de Magritte. Elle donne naissance à une série qu’il poursuit tout au long de sa carrière sous le titre La Trahison des images et qui est symbolisée par l’œuvre représentant une pipe de la manière la plus réaliste qui soit et portant la légende Ceci n’est pas une pipe (1928-1929). C’est en 1923 que Magritte se rapproche des Surréalistes après avoir découvert la peinture de De Chirico Le Chant d’amour (1914) qui l’émut au plus haut point. Par la suite, il rencontre en 1927 André Breton et son groupe surréaliste qui trouve ses inspirations dans les théories psychanalytiques de Freud.

Les compositions surréalistes de Magritte refusent tout embellissement sentimental pour n’exprimer que le mystère de nos pensées profondes avec des images énigmatiques. Magritte cherche ainsi à confondre le spectateur avec des représentations déroutantes et des associations d’éléments inégaux sans aucune relation entre eux. L’œuvre doit désorienter. Mais à la différence de certains surréalistes, Magritte n’entend pas faire appel à l’imaginaire du rêve et de l’inconscient qui par nature pourrait expliquer et justifier ses créations. Au contraire, l’artiste mobilise son talent pour dépeindre un ordre mystérieux « qui interdit à la pensée de se satisfaire des interrogations que l’on pourrait poser et des réponses que l’on pourrait trouver ». Dans son essai La Peinture inutile de M. (1979), Magritte souligne l’absolue nécessité que les choses représentées restent des « énigmes échappant aux investigations scientifiques ». Ainsi, la présente œuvre ne peut-elle être lue à la lumière du sens et de l’ordre signifiant-signifié. Magritte revendique dans ses écrits comme dans ses tableaux la volonté « d’échapper à l’idée fixe » et de recherche à stimuler le mouvement permanent de l’esprit pour lequel rien ne saurait s’immobiliser. Les Grains de Beauté est une démonstration évidente de ce parti pris.

Le sol terreux et l’horizon dépouillé desquels surgit la pierre centrale de la présente œuvre, matérialisent le vœu de Magritte de représenter une épure de la réalité. Cette toile ne figure aucun être vivant, humain, animal ou végétal et pourtant la vie y est présente. Et de fait, les motifs du tableau sont difficilement nommables, conformément à l’intention de l’artiste d’extraire les objets de leur contexte pour leur donner une nouvelle évidence. Car chez Magritte, l’art de la référence va de pair avec celui du brouillage de piste. L’esprit du spectateur est alors plongé dans l’incertitude et nourri de ce doute fondamental qui est pour l’artiste au cœur de l’énigme et de l’interrogation qu’elle fait naître.

Le plan de la composition est à la fois simple mais impénétrable. L’ancrage massif du menhir central contraste avec la légèreté des fragments de pierres en lévitation, comme suspendus dans une action invisible. La gamme de couleur est rustique et réduite à trois tons : le gris, le rouge et le brun. On remarque une très légère ombre à la gauche du rocher principal, seule marque de relief évidente. L’absence de source de lumière constatée, le défaut de perspective renforcé par la platitude de la matière contribuent à anonymiser et dépouiller cette composition à son paroxysme. Seul le dégradé rougeoyant du fond pourrait indiquer une temporalité (crépuscule ou aube ?) dans cette œuvre où rien ne permet de situer, dater ou analyser la représentation.

Magritte aimait les pierres, car « elles ne pensent pas » ! Dès les années 1950, Magritte réalise une série d’œuvre intitulée « l’art de la conversation » où l’artiste poursuit un travail sur le mot et la représentation. Dans différentes variantes, l’artiste décline des mots monumentaux taillés dans la pierre (rêve, amour…), les lettres s’empilant comme les éléments d’un mur. Mais les cailloux, mégalithes et autres rochers magrittiens sont aussi à prendre comme des êtres purs qui, libérés de leur poids et présence monumentales, sont capables de lévitation et de transformations (La Clé de verre, 1959). Rejoignant la mer et flottant dans les nuages (La Flèche de Zénon, 1964) ou abritant des ilots imaginaires (Le Château des Pyrénées, 1959), les pierres-planètes de Magritte figurent un monde nouveau, souverain et si pur que l’on peut se demander s’il s’agit du premier atome de matière ou de notre planète après la fin du monde.

Par sa matière minérale et froide, la pierre permet de mettre à distance et de dépersonnaliser les terres d’accueil des interrogations et provocations de Magritte. Ce dépouillement est nécessaire pour privilégier la force du choc attendu du non-message contenu dans les œuvres de l’artiste. La dureté et la solidité de ce matériau évoquent l’immuable, l’inamovible et l’éternel. Dans l’œuvre La Chant de la Violette (1951) Magritte représente deux personnages tirés d’un quotidien vraisemblablement assez banal (un des deux hommes portant un pain sous le bras) mais qui sont constitués de pierre, tels les corps retrouvés à Pompéi et pétrifiés en pleine action par l’éruption du Vésuve. L’usage de la pierre permet à Magritte de créer une atmosphère hors-temps et sans temporalité où la notion d’infini plane. Les hommes sont ils morts ou vivants ? Ces masses minérales viennent-elles de l’espace telles des aérolithes ou météorites ou sont-elles des débris de notre terre disparue?

Dans Les Grains de Beauté, l’opposition entre l’épaisseur du bloc de pierre central et la volatilité des éléments qui s’en détachent, instille un message confus et embarrassant pour nos esprits dépourvus de repères symboliques. Pas d’acteur de ce big-bang, pas de son, de cause ou de conséquences de cette fraction du tout en éléments dispersés. Le temps est suspendu. Le dépouillement de la composition ne laisse aucun indice et réduit tout encouragement à l’analyse scientifique de l’image. En l’absence valeur narrative, l’œuvre s’impose à nous en faisant appel à notre compréhension instinctive.

A l’évidence, on ne peut ignorer la connotation sexuelle de cette œuvre d’un artiste qui ne cacha pas son goût pour la suggestion érotique, sa « période vache » (vers 1948) en témoigne. Aussi, l’irruption de cet appendice phallique d’une terre stérile et la projection de petites entités dans cet univers organique est-elle sans équivoque. On peut également se demander si le choix de la pierre pour incarner cette éminence n’est pas synonyme de virilité et si la couleur rosée du fond n’est pas une métaphore de la chair ? Parallèlement, l’attribution et la répartition des couleurs paraît-elle évoquer la rencontre des univers féminin et masculin.

Le titre Les Grains de Beauté n’offre pas non plus d’élément de compréhension rationnelle et vient -au contraire- renforcer l’état de questionnement sans réponse du spectateur. Les titres de Magritte fonctionnent souvent comme un facteur supplémentaire critique et perturbateur. Cet intitulé n’est cependant pas totalement étranger à la vision proposée. Qu’elles s’en détache ou s’apprêtent à le rencontrer, les météorites entourant le bloc de pierre entretiennent une relation avec lui. Grace au mécanisme d’association d’idées, l’artiste suscite aussi une réflexion sur le concept de beauté et de laideur, le spectateur ne pouvant s’empêcher de chercher un lien entre la représentation et son titre. Mais la question reste ouverte…. Cette œuvre est une démonstration du génie de Magritte à nous mettre en état d’incertitude et à contester la logique même de la représentation : « L’invisible n’est pas caché au regard ».

L’artiste ici nous offre de partager son immense goût pour la liberté, celle de penser l’image comme un miroir de notre perception du monde. Le charme de l’étrange souhaité ici par l’artiste, nous autorise à douter de l’obligation de ressentir un sentiment déterminé par ce que nous regardons. La proposition artistique de Magritte réunit, l’espace d’un instant, la vision d’une chose familière, le sentiment de l’étrange et nous-même, sans que le peintre ne puisse décider quel sentiment son tableau doit provoquer. C’est là la démonstration de l’immense modernité du talent et de la puissance intellectuelle de l’artiste qui nous propose une autonomie et une responsabilité totales devant l’œuvre.

"My paintings are valuable, in my eyes, if the objects they represent resist interpretation by symbols or by other explanations."

René Magritte.

In this statement, the artist René Magritte sets out a high intellectual and artistic standard, for which our work Les Grains de Beauté, painted in circa 1965, is one of the best examples.

Some of Magritte's works appear to be hermetically sealed in on themselves, resistant to any rational attempt at analysis. Unique, autonomous and self-sufficient, Magritte's paintings seem to have no need for parallels or lineage for their essence is to raise questions about reality and to represent the strange in its most basic manifestations.

Throughout his career, the artist showcased the enigmatic by creating incongruous relationships between objects in his paintings or between the main qualities of the elements in the composition. The artist experimented with aspect ratios, the laws of gravity and the identities attributed to objects by consensus in order to deprive them of their utilitarian value. This approach gives us a new perspective and expands the living space of everyday objects. By representing the inexplicable and the unexplained, Magritte expressed his desire to shed light on mystery.

A questioning of the nature of things and the relationship between language and representation appeared very early in Magritte's painting. This resulted in a series that he continued throughout his career entitled La Trahison des images, symbolised by piece depicting a standard pipe, bearing the caption Ceci n’est pas une pipe (1928–1929). In 1923, Magritte adopted a more Surrealist approach after discovering De Chirico's painting Le Chant d’amour (1914), which he found exceptionally moving. In 1927, he met André Breton and his Surrealist group, which was inspired by the psychoanalytical theories of Freud.

Magritte's Surrealist compositions refuse any sentimental embellishment, expressing only the mystery of our deepest thoughts with enigmatic images. Magritte thus sought to confuse the viewer with disconcerting representations and combinations of mismatched elements unrelated to one another. The piece must disorientate. But unlike some Surrealists, Magritte did not intend to appeal to the imaginary world of dream and unconscious which, by their nature, could explain and justify his creations. Instead, the artist mobilised his talent to depict a mysterious order "which forbids thought to be satisfied with the questions we may ask and the answers we may find".

In his essay La Peinture inutile de M (1979), Magritte stressed the absolute necessity that the objects in his paintings remained “enigmas that escape scientific investigation". Thus, our work cannot be understood in the light of meaning and in a signifier-signified context. In both his writing and his painting, Magritte claimed to want to "escape fixed ideas" and sought to stimulate the permanent movement of the spirit for which nothing stands still. Our work is a clear demonstration of this bias.

The earthy ground and bare horizon from which the central stone of this piece emerges, depict Magritte's desire to present a purification of reality. There are no living creatures, humans, animals or plants, and yet life is present. The motifs in the painting are difficult to name, in keeping with the artist's intention to remove objects from their typical context to offer a new perspective. With Magritte, the art of reference goes hand in hand with the art of covering his tracks. The viewer's mind is then plunged into uncertainty and nourished by this fundamental doubt which, for the artist, is at the heart of the enigma and the questioning it evokes.

The foreground of the composition is both simple and impenetrable. The solid anchoring of the central menhir contrasts with the light stone fragments, levitating as if suspended in invisible action. The colour palette is rustic and reduced to three tones: grey, red and brown. There is a very slight shadow to the left of the main rock – the only obvious texture. The lack of any light source or perspective, enhanced by the flat material, combine to anonymise and strip this composition to the limit. Only the reddish shading of the background might indicate a sense of time (dusk or dawn?) in this piece which is absent of identifiers to locate, date or analyse the representation.

Magritte loved stones because "they don't think"! From the 1950s onwards, Magritte produced a series of pieces entitled "The Art of Conversation" where the artist continued his work on words and representation. In various forms, the artist set out monumental words carved in stone (dream, love, etc.), the letters stacking up like the pieces in a wall. But Magritte's stones, megaliths and other rocks are also to be understood as pure beings which, freed from their weight and monumental presence, are capable of levitation and transformation (La Clé de verre, 1959). Joining the sea and floating in the clouds (La Flèche de Zénon, 1964) or housing imaginary islands (Le Château des Pyrénées, 1959), Magritte's planet-stones symbolise a new world, so sovereign and pure that one wonders if it is the first atom of matter or our planet after the end of the world.

In cold mineral material, stone makes it possible to distance and depersonalise the host lands of Magritte's questions and provocations. This starkness is necessary to emphasise the expected shock of the non-message contained within the artist's works. The hardness and solidity of this material evoke the unchanging, the immovable and the eternal. In La Chant de la Violette (1951), Magritte depicts two figures drawn from what appears a relatively mundane everyday world (one of the two men is carrying a loaf of bread under his arm), but in stone, like the bodies found in Pompeii, fossilised in action by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The use of stone allows Magritte to create a timeless ambiance free of temporality with a lingering sense of infinity. Are the men dead or alive? Do these mineral masses come from space like aeroliths or meteorites or are they debris from our extinct earth?

In our painting, the opposition between the thickness of the central block of stone and the volatility of the detached elements instils a confused and awkward message in our minds devoid of symbolic reference points. There are no participants in this big bang, no sound, cause or consequences for this fraction of the whole in dispersed elements. Time is suspended. The sparseness of the composition leaves no clues and reduces any incentive for scientific analysis of the image. In the absence of narrative value, the work imposes itself on us by appealing to our instinctive understanding.

Of course, we cannot ignore the sexual connotations of this work by an artist who revealed a taste for erotic suggestion in his "période vache" (circa 1948). The irruption of this phallic appendage from a barren land and the projection of small entities into the organic universe is clear for all to see. The viewer may also wonder whether the decision to depict this eminence in stone is symbolic of virility and whether the pinkish background colour is a metaphor for the flesh. At the same time, the allocation and distribution of colour appears to evoke the meeting of the feminine and masculine worlds.

The title Les Grains de Beauté does not offer any element of rational understanding either but, rather, reinforces the unanswered questions in the viewer. Magritte's titles often function as an additional critical and disturbing factor. However, this title is not totally unrelated to the image. The meteorites surrounding the block of stone relate to it, whether detached or poised to meet it. Thanks to the association of ideas, the artist also encourages a reflection on the concept of beauty and ugliness, as the viewer cannot help but look for a link between the representation and its title. But the question remains... This work demonstrates Magritte's genius in putting us in a state of uncertainty and challenging the very logic of representation: “The invisible is not hidden from view."

The artist offers to share his immense desire for freedom, to think of the image as a mirror of our perception of the world. The charm of the unusual, desired here by the artist, allows us to doubt the need to feel something on the basis of what we’re looking at. For a time, Magritte's artistic proposal unites a vision of something familiar, the sense of the unusual and ourselves, with the painter unable to decide which feeling his painting should evoke. This demonstrates the immense modernity of the talent and intellectual power of the artist who gives us total autonomy and responsibility as we view the piece.

| Artist: | René Magritte (1898 - 1967) |

|---|---|

| Applied technique: | Oil on canvas |

| Auction house category: | Paintings |

| Artist: | René Magritte (1898 - 1967) |

|---|---|

| Applied technique: | Oil on canvas |

| Auction house category: | Paintings |

| Address of auction |

CHRISTIE'S 9 Avenue Matignon 75008 Paris France | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preview |

| ||||||||||||||

| Phone | +33 (0)1 40 76 85 85 | ||||||||||||||

| Fax | +33 (0)1 40 76 85 86 | ||||||||||||||

| Conditions of purchase | Conditions of purchase | ||||||||||||||

| Shipping |

Postal service Courier service pickup by yourself | ||||||||||||||

| Payment methods |

Wire Transfer | ||||||||||||||

| Business hours | Business hours

|