Birmingham silver - the beauty and elegance of small forms

Birmingham silver holds an esteemed place in museum exhibitions and is highly valued by antique collectors. The city is often referred to as the silver capital of the United Kingdom because it was home to numerous workshops that supplied Europe with exquisite tableware and trinkets. Birmingham silver was purchased by members of royal families, and the Russian imperial court was a regular client of British silversmiths. Birmingham jewelers were renowned for their small-form items with delicate and intricate finishing.

Birmingham silver. Elkington and Co. Jug and glasses, 1870

Birmingham silver. Elkington and Co. Jug and glasses, 1870

History of the Silver Industry in Birmingham

Birmingham silver didn't gain prominence right away. Workshops in the city had been operating since the 15th century, but the local jewelry industry truly blossomed during the reign of Charles II. The monarch spent several years in France, where he sought refuge due to Oliver Cromwell's rise to power. At the French royal court, extravagant attire adorned with elaborate buttons, buckles, and precious gemstones was in vogue. Thanks to Charles, the Parisian style became popular among British nobility, who inundated workshops with orders for silver accessories.

Birmingham silver. Simon Peters Verelst. Charles II, King of England, 1630-1685

Birmingham silver. Simon Peters Verelst. Charles II, King of England, 1630-1685

Birmingham silver became highly sought after as the city's jewelers specialized in producing small items starting from the mid-17th century, including buttons, writing instruments, scent bottles, flasks, and toothpicks. Matthew Boulton, the heir to a family toy manufacturing business, played a significant role during this period. At the age of seventeen, this hereditary jeweler invented an original method of enamel inlaying for buckles, allowing him to secretly export these items to France and later import them as the latest Parisian creations.

Birmingham silver. Matthew Boulton. Soup tureen, 1811

Birmingham silver. Matthew Boulton. Soup tureen, 1811

Boulton understood that Birmingham would never fully develop its trade connections as long as the hallmarking was done in London. Leveraging his connections in Parliament, he lobbied for a law that granted Birmingham and Sheffield the right to independently hallmark gold and silver. The origins of the symbols on the hallmarks are linked to the names of the London hotel "The Crown and Anchor," where representatives of both cities stayed during the law's discussion. The symbols seemed equally favorable, so the jewelers decided by a coin toss. Birmingham received the anchor, and Sheffield received the crown (later changed to a rose).

Birmingham silver. Birmingham branding

Birmingham silver. Birmingham branding

The Birmingham Assay Office was established in 1773. Initially, the institution occupied three rooms in the "Royal Head" hotel, and its staff consisted of four people. The controllers verified the purity of the silver and confirmed compliance with the sterling silver standard by applying a hallmark. Matthew Boulton himself became the first customer of the assayers.

Four stamps were applied to Birmingham silver:

- The hallmark (92.75% pure silver) – a left-facing lion figure.

- The city symbol – an anchor.

- The date represented by a letter of the alphabet.

- The workshop's mark.

Birmingham silver. Matthew Boulton's branding

Birmingham silver. Matthew Boulton's branding

The ability to verify silver on-site relieved jewelers of the expenses associated with lengthy trips during which a batch of goods could be stolen, damaged, or copied. The legislative change spurred the development of the jewelry production industry in Birmingham. In subsequent years, new enterprises emerged in the city, many of which gained worldwide recognition.

Birmingham silver. Elkington and Co. Bowl, 1901-1902

Birmingham silver. Elkington and Co. Bowl, 1901-1902

Birmingham Silvermiths

Nathaniel Mills Sr. registered his hallmark in 1803. He was the first jeweler to create silver souvenirs featuring British landmarks. He placed these images on snuffboxes, card cases, and caskets. Tourists eagerly bought these trinkets, helping the master gain recognition beyond the borders of the United Kingdom. The finest products of the Mills factory appeared after 1830 when the craftsmen mastered casting, stamping, and mechanical silver processing.

Birmingham silver. Nathaniel Mills. Abbotsford House cigarette case, 1838

Birmingham silver. Nathaniel Mills. Abbotsford House cigarette case, 1838

The firm Elkington & Co achieved success through collaboration with Benjamin Schlick, a Danish mechanic and architect who moved to England in the mid-19th century. The master created designs and casts inspired by antiquity and the Renaissance for jewelers. There are records that the architect was responsible for receiving the Russian Emperor Nicholas I, who visited the enterprise in 1844. Later, Schlick presented several items as a gift to Princess Maria Alexandrovna.

Birmingham silver. Elkington and Co. Benjamin Schlick Project. Cup and saucer, 1850s

Birmingham silver. Elkington and Co. Benjamin Schlick Project. Cup and saucer, 1850s

Henry Matthews registered his company in 1894. The firm specialized in small-sized items with detailed finishing. The factory produced toys and accessories: hatpins, hairbrushes, snuffboxes, eyeglass frames. The enterprise ceased operations in 1930.

Birmingham silver. The firm of Henry Matthews. Miniature Coronation Throne. 1901-1902

Birmingham silver. The firm of Henry Matthews. Miniature Coronation Throne. 1901-1902

Birmingham silver remains popular worldwide today. There is a jewelry quarter in the city where craftsmen prefer silver over other precious metals. Here, tourists can purchase unique jewelry and souvenirs at affordable prices. A permanent exhibition of antique silver is organized at the City Museum of Jewelry Art.

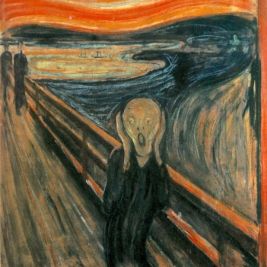

The painting "The Scream" by Edvard Munch is a terrifying prophetic symbol of the 20th century

The painting "The Scream" by Edvard Munch is a terrifying prophetic symbol of the 20th century  The Renaissance of Historic Tapestries

The Renaissance of Historic Tapestries  The painting " The Whirlwind" by Filipp Andreevich Malyavin is an inspiring hymn to the beauty and strength of character of Russian peasant women

The painting " The Whirlwind" by Filipp Andreevich Malyavin is an inspiring hymn to the beauty and strength of character of Russian peasant women  Pastoral is an elegant and carefree genre of art from the Baroque and Rococo periods

Pastoral is an elegant and carefree genre of art from the Baroque and Rococo periods  The Timeless Charm of Vintage Ephemera: A Collector's Guide

The Timeless Charm of Vintage Ephemera: A Collector's Guide  The religious genre is profoundly spiritual and sincere art

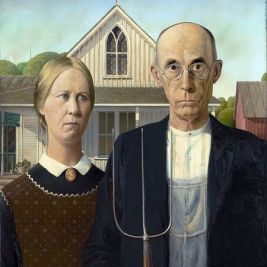

The religious genre is profoundly spiritual and sincere art  Regionalism is an American art movement that celebrates the beauty of simple provincial life

Regionalism is an American art movement that celebrates the beauty of simple provincial life  Anatoly Zverev — an unrecognized genius of the Soviet era

Anatoly Zverev — an unrecognized genius of the Soviet era  Expressionism - a shocking emotional movement in 20th-century art

Expressionism - a shocking emotional movement in 20th-century art  The National Order of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour