Silver of Great Britain - History, Styles, and Hallmarks

British Silver is renowned for its high artistic value and continues to adorn the world's finest museums today. Creations by British silversmiths were sought after by the European elite, and one of the largest buyers was the Russian Imperial House, which is why the world's biggest collections of early British silver are housed in the Hermitage Museum and the Armoury Chamber. English museums cannot boast such a rich exhibition due to the mass melting of precious metal objects during the mid-17th-century civil war.

British Silver. Gabriel Smith. The Punch Bowl, 1710-1711

British Silver. Gabriel Smith. The Punch Bowl, 1710-1711

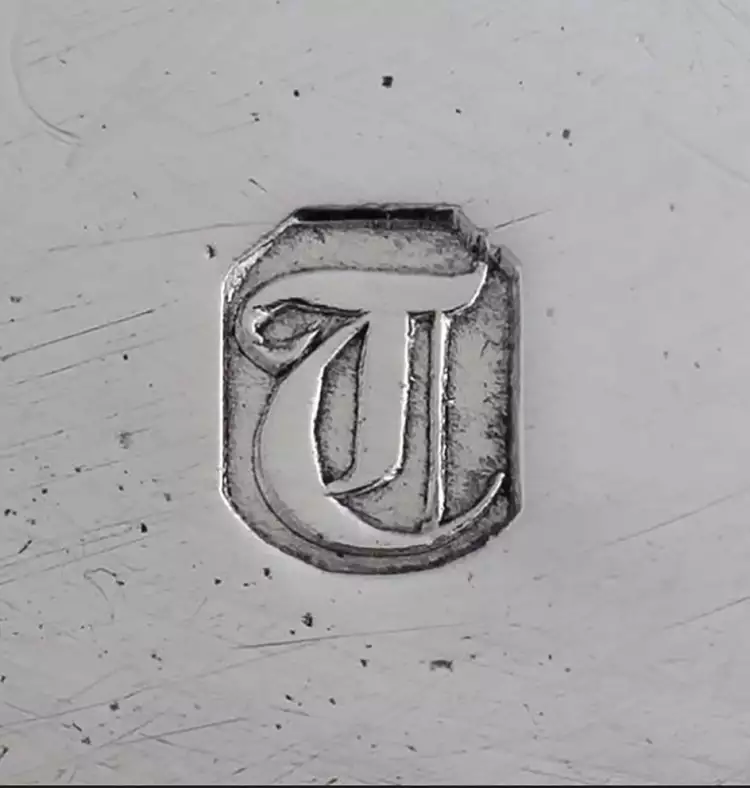

Hallmarking of Silver Items in England

Identifying British Silver is relatively easy due to a well-documented hallmarking system. The hallmarking of silver items in England began in 1238 when Henry III issued a decree to introduce a royal standard for jewelers. The alloy had to contain at least 92.5% silver, which was verified by a group of six master craftsmen. Starting from 1300, selected guild jewelers were responsible for inspecting all items for compliance with the so-called Sterling Standard and marking them with a hallmark of a crowned leopard's head.

British Silver. Branded with a leopard's head

British Silver. Branded with a leopard's head

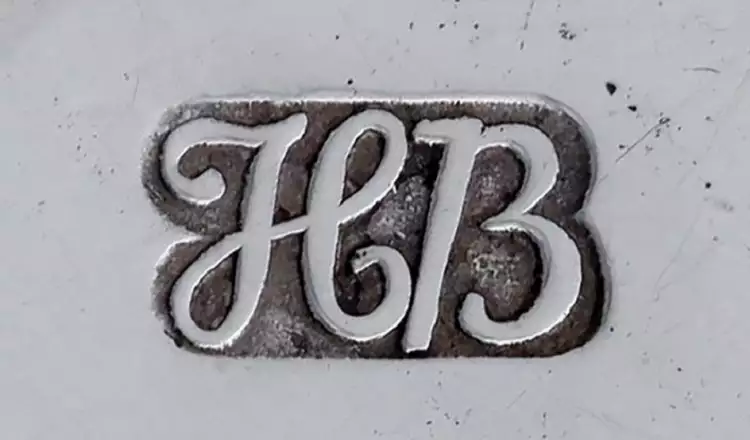

Silver in Great Britain was required to be hallmarked not only in London but also across the country. In 1327, the control function was entrusted to representatives of the Craft Guild, and without their inspection, an item could not be sold. Initially, inspectors themselves visited workshops, but later, the duty of bringing items for inspection was shifted to the jewelers themselves. Guilds owned hall buildings where a separate hall was allocated for hallmarking. From 1363, additional workshop marks were added to the royal hallmark.

In 1478, a new mark in the form of a letter denoting the year of manufacture appeared. When the alphabet was exhausted, it started again, with slight modifications to the marking. In 1544, additional stamps indicating the city of production were introduced. The first was the hallmark of London in the form of a walking lion, followed by individual marks for Birmingham, Sheffield, Edinburgh, and Dublin. Therefore, it is straightforward to trace the history of any item from English workshops today.

British Silver. Birmingham branding

British Silver. Birmingham branding

British Silver. Year of manufacture

British Silver. Year of manufacture

Early English Silver

Despite the abundance of information about the English hallmarking system, very few items from the early period have survived. It is known that silver was used to create tableware, but any damaged or heavily worn object was immediately sent for melting. Any notable Briton had their own silver spoon that they carried with them while traveling. The church commissioned jewelers to create communion cups, which were made from a single piece of sheet metal and polished with pumice.

British Silver. Benson Wodewos spoon collection, 15th century

British Silver. Benson Wodewos spoon collection, 15th century

The progress of silversmithing was hindered by a lack of raw materials, which became a significant problem for the economies of European countries in the 15th century. During that time, jewelers worked more with gold because it was easier to obtain. The plague epidemic significantly reduced the population, causing difficulties in transporting ingots from the East. Partly solving the problem was the discovery of new mines in Saxony and Tyrol, and in 1471, Italy was included in the list of major silver suppliers.

British Silver. Robert Medley. Communion Cup, 1569

British Silver. Robert Medley. Communion Cup, 1569

True flourishing of the jewelry art was achieved during the Tudor era. Queen Elizabeth I highly valued extravagant silverware, which was customary to gild in those times. Masters melted gold and mixed it with mercury, then applied the composition to the surface of the object and fired it. Mercury evaporated during heating, and the coating firmly adhered to the silver. The process was hazardous both for the jeweler and the owner of the silverware.

British Silver. John Spielman. Gilded Whitfield silver goblet, 1590

British Silver. John Spielman. Gilded Whitfield silver goblet, 1590

British Silver. Flint Roger I. Two feet joined in the form of a barrel, 1572-1573

British Silver. Flint Roger I. Two feet joined in the form of a barrel, 1572-1573

During the peak of the Renaissance, English silversmithing was strongly influenced by German, Italian, and Dutch masters, which was reflected in the decorative elements of the pieces. Engraving and embossing adorned the silverware, with botanical ornamentation taking center stage. However, in 1603, Elizabeth was succeeded on the throne by the Puritan James I, who was a staunch opponent of luxury. During his reign, gilding of silver was nearly abandoned, and preference was given to simple lines and smooth forms.

British Silver in the 18th Century

After the decline caused by the revolution, a period of restoration followed. During the rule of Charles II, the style of Dutch and French masters gained wide popularity among the English aristocracy. Vases, pitchers, and toilet accessories were adorned with lavish Baroque ornamentation featuring an abundance of acanthus leaves, flowers, and figurines characteristic of engravings by Dutch artists. Forms borrowed from Chinese porcelain became fashionable, spurred by the active activities of the East India Company.

British Silver. Leonard Krug. A goblet with lid, circa 1612

British Silver. Leonard Krug. A goblet with lid, circa 1612

The ascension of Puritan William III brought the craftsmen's style back to simplicity. This direction went down in history as Queen Anne style, characterized by simple noble lines, restrained proportions, and smooth finish. Traditional English two-handled cups and mugs of particular shapes remained popular and remained in demand for the next two centuries.

British Silver. Richard Green. Mug, 1712-1713

British Silver. Richard Green. Mug, 1712-1713

The mass influx of Huguenot craftsmen from France in the 18th century led to the emergence of new pieces of elegant and ornate tableware, such as plademenaiges, sauceboats, terrines, and spice containers. Decorative rococo techniques with rocailles, flowers, and maritime elements showcased all the plastic possibilities of silver. One of the striking manifestations of this style was the chinoiserie direction, influenced by Chinese exoticism.

British Silver. White Fuller. Teapot, 1757-1758

British Silver. White Fuller. Teapot, 1757-1758

Starting from the 1770s, neoclassicism replaced rococo. Massive wine fountains and bulky plademenaiges gradually gave way to light ewers, oval jugs, and various jugs. Lavish decorations went out of fashion, and jewelers focused on creating complete sets of tableware in a unified style. The main role in the finishing was played by restrained decor inspired by classical architecture.

British Silver. Anne Batman. Basket, 1799-1800

British Silver. Anne Batman. Basket, 1799-1800

The firm Rundell, Bridge & Rundell, the largest jewelry manufacturer at that time, became widely known. The innovative techniques of the company's masters greatly influenced the development of silversmithing during Queen Victoria's era. The company's owners were the first to open an art studio, where projects based on the works of Gothic and Mannerist masters were created.

British Silver. Rundell, Bridge and Rundell. Soup tureen, stand and liner, 1828-1829

British Silver. Rundell, Bridge and Rundell. Soup tureen, stand and liner, 1828-1829

Victorian Silver

In the early 19th century, another major silver manufacturer emerged - the firm Mortimer and Hunt, which made a significant contribution to the formation of the Victorian style. The company's artists partly repeated the forms of table decorations of the previous century, but significantly expanded their assortment. Commemorative cups, memorial prizes, gift items in the form of cups, unusual vases, urns, and sculptural compositions appeared. British pieces were characterized by deep symbolic and meaningful content. During Queen Victoria's reign, the trend of awarding silver trophies for military feats, achievements in sports, and charitable endeavors became widespread, leading to a surge of orders for items in the national style.

In 1830, the firm of James and Sebastian Garrard received the title of Royal Warrant Holders. The brothers appointed the sculptor Edward Cottrell as a project developer, an advocate of the naturalistic style. The master's works played a significant role in promoting the firm and were recognized at the 1871 World Exhibition.

British Silver. Robert Garrard. Buliotka with a tagan and a spirit flame, 1880-1881

British Silver. Robert Garrard. Buliotka with a tagan and a spirit flame, 1880-1881

British silver was highly valued both within and outside the country. The development of industry and the cost reduction of mass-produced items allowed even middle-income families to afford precious tableware. Silver services were a sign of wealth and passed down through generations. With the emergence of more practical materials, the popularity of silver gradually waned, but at antique auctions, items from English masters remain highly sought after.

German Porcelain: History of Creation and Development

German Porcelain: History of Creation and Development  Allegory: Essence, Distinctive Features, History in Art

Allegory: Essence, Distinctive Features, History in Art  Gothic - the mystical art of the Middle Ages

Gothic - the mystical art of the Middle Ages  The painting "Menshikov in Berezovo" by Vasily Surikov is a dramatic depiction of the life of the disgraced prince

The painting "Menshikov in Berezovo" by Vasily Surikov is a dramatic depiction of the life of the disgraced prince  Embracing Anti-Design - The Bold New Wave in 2024

Embracing Anti-Design - The Bold New Wave in 2024  Baroque is an exquisite pearl of European culture: essence, developmental history, style features

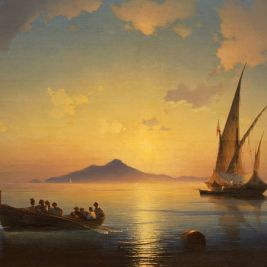

Baroque is an exquisite pearl of European culture: essence, developmental history, style features  The painting "Bay of Naples" by Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky is an invitation to immerse yourself in the serene beauty of a southern evening

The painting "Bay of Naples" by Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky is an invitation to immerse yourself in the serene beauty of a southern evening  Anatoly Zverev — an unrecognized genius of the Soviet era

Anatoly Zverev — an unrecognized genius of the Soviet era  Edward Munch—the creator of nightmares and the singer of anxiety

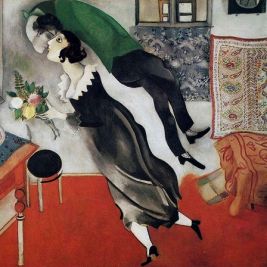

Edward Munch—the creator of nightmares and the singer of anxiety  The painting "The birthday" by Marc Chagall is an ode to love capable of soaring above the everyday

The painting "The birthday" by Marc Chagall is an ode to love capable of soaring above the everyday