Romanticism: Wings of Freedom and Inspiration

Romanticism is a grand ideological and artistic movement in the culture and art of the 19th century, replacing the cold rationalism of neoclassicism and the Enlightenment. Romantics elevated the importance of imagination, emotions, feelings, and inner turmoil. In literature and art, an era of heroes with strong, daring, contradictory, and sometimes rebellious characters began. These are figures of the Byronian and Promethean types who either proclaim the greatness of humanity or become toys in the hands of fate. Passions engulf them; they embark on journeys and climb barricades, raising the banner of freedom and knowing no rest.

Romanticism. Théodore Géricault. The Raft of the Medusa, 1818-1819

Romanticism. Théodore Géricault. The Raft of the Medusa, 1818-1819

Romanticism in painting rejected the rationality of classicism and reflected an interest in the depths of human personality, characteristic of romantic philosophy. It grew on the emotional ground of sentimentalism but, while retaining lyricism and poetic qualities, replaced sentimental sensitivity with dramatic manifestations of human nature. Therefore, it should not be associated with pastoral motifs but rather with the romance of distant travels, expeditions, mysterious discoveries, and even revolutionary struggles. Unlike sentimentalism, romanticism lacks sentimentality and tearfulness; it is a philosophy of the bold and the strong.

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. Battle of the Giaour and the Pasha, 1826

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. Battle of the Giaour and the Pasha, 1826

The paintings of the romantic era are characterized by high artistic expressiveness:

- They have fewer geometric schemes than classical canvases.

- There are more effects aimed at arousing emotions in the viewer and even evoking a sense of involvement in the events.

- Compositions are dynamic.

- Instead of strict lines, dynamic outlines (which will later be intensified in the flowing lines of the modern era).

- Instead of cold and ideal beauty, there is an aesthetics of passion, remarkably combined with lyricism.

- Instead of theatricality, there is vibrant life.

Romanticism. Antoine-Jean Gros. Bonaparte at the Pont d'Arcole, 1796

Romanticism. Antoine-Jean Gros. Bonaparte at the Pont d'Arcole, 1796

The characters and plots of Romanticism

The characters in the paintings of Romantic artists resemble the heroes of literary novels: finely sensitive, often mysterious, sometimes rebellious, sometimes impassioned, and often lonely.

Romanticism. Caspar David Friedrich. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818

Romanticism. Caspar David Friedrich. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818

Many creators delved into the exploration of the dark sides of human nature. Hence, the painters' interest in the night, thunderstorms, and mysticism.

Romanticism. Johann Heinrich Füssli. The Nightmare, 1781

Romanticism. Johann Heinrich Füssli. The Nightmare, 1781

To some extent, the masters of Romanticism even returned to the aesthetics of the Baroque with its dramatic intensity, passion, dynamism, chaos, and mysticism. Many tools enhancing the expressiveness of the imagery were borrowed from the Baroque, including compositional dynamics and chiaroscuro effects. However, unlike Baroque art, the creative platform of the Romantics was based not on solemn pomp but on naturalness and sincerity in conveying feelings.

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. Turks

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. Turks

The philosophy of the Romantic era influenced the evolution of the portrait genre. Romantic painters did not create formal portraits. They sought to reveal human individuality, convey the richness of the inner world, pour the tension of experiences onto the canvas, reflect emotions, and convey character.

Romanticism. Jan Matejko. Stańczyk, 1862

Romanticism. Jan Matejko. Stańczyk, 1862

Many artists explored the theme of the tormented soul. An example of such a theme is the work of Théodore Géricault, "The Insane Woman, Suffering from Obsession with Gambling."

Romanticism. Théodore Géricault. The Woman with a Gambling Mania, 1822

Romanticism. Théodore Géricault. The Woman with a Gambling Mania, 1822

Painters boldly delved into the dark wells of the soul, studied hidden turmoil, and depicted the complexity of human nature, where good and evil often intertwine.

Romanticism. Gustave Courbet. Self-portrait (The Desperate Man), 1843-1845

Romanticism. Gustave Courbet. Self-portrait (The Desperate Man), 1843-1845

The subjects of the paintings also reflect Romantic tendencies: painters turned to emotional, stirring themes.

Romanticism. Francisco de Goya. The Second of May 1808, 1814

Romanticism. Francisco de Goya. The Second of May 1808, 1814

Of course, exciting, dramatic, and epic subjects were present in visual art earlier as well. But Romantic artists avoided proclaiming abstract ideals and theatricality, instead, they filtered themes through the prism of the human soul. Therefore, when looking at these paintings, whether it's Théodore Géricault's "The Raft of the Medusa" or Karl Pavlovich Bryullov's "The Last Day of Pompeii," we empathize with the heroes of these canvases, imagine ourselves in their place, and almost physically transport ourselves to the open sea or the foot of Mount Vesuvius.

Romanticism. Karl Bryullov. The death of Inessa de Castro, 1841

Romantic Landscapes

Romantic landscapes are a tribute to the profound interest of painters of this movement in nature, the purity of which romantic philosophers juxtaposed with rationalistic civilization (even creating the archetype of the "noble savage").

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. Natchez, 1834-1835

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. Natchez, 1834-1835

The landscape genre flourishes. It is the era of renowned landscape artists, such as William Turner.

Romanticism. William Turner. The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, 1835

Romanticism. William Turner. The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, 1835

The restless spirit of the Romantics awakened an interest in exotic realms and the fury of the elements. An expressive example is the works of the eminent marine painter Ivan Aivazovsky.

Romanticism. Ivan Aivazovsky. Wave, 1889

Romanticism. Ivan Aivazovsky. Wave, 1889

Many Romantic painters, especially Germans, poeticized the night. A unique "night genre" even emerged, celebrating the mystique and unreality of the world in the moon's glow or in the moonless darkness.

Romanticism. Caspar David Friedrich. Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon, 1824

Romanticism. Caspar David Friedrich. Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon, 1824

By poeticizing nature, artists made it a full-fledged protagonist of narrative canvases.

Romanticism. Karl Friedrich Lessing. Knight's Castle, 1828

Romanticism. Karl Friedrich Lessing. Knight's Castle, 1828

Landscapes ceased to be mere backgrounds. In many works of Romantic masters, characters grapple with the elements. In others, natural phenomena accentuate the emotional experiences of the heroes.

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. The Bride of Abydos, 1852-1853

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. The Bride of Abydos, 1852-1853

Romantic landscape artists loved to depict thunderstorms, storms, tempests, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions.

Romanticism. Karl Bryullov. The Last Day of Pompeii, 1833

Romanticism. Karl Bryullov. The Last Day of Pompeii, 1833

They admired the untamed beauty of natural forces and relished the emotional impact of their creations on the viewer.

Romanticism. Théodore Géricault. Mazeppa, 1820

Rebellious Romantic Painters

Romanticism in painting emerged in the 1820s and 1830s. Romantic painters actively opposed Neoclassicism and, in particular, its canonical version—conservative Academicism. Fierce ideological battles raged between the Romantics and the Academics!

Romanticism. Francisco de Goya. The Third of May 1808, 1814

Romanticism. Francisco de Goya. The Third of May 1808, 1814

In this, the Romantic artists resembled their heroes: they boldly went against public opinion, rejected dogmas, and challenged established traditions.

Romanticism. Francisco de Goya. Maja and Celestina on the balcony, 1808-1812

Romanticism. Francisco de Goya. Maja and Celestina on the balcony, 1808-1812

One of the first battles was fought by Théodore Géricault. It is from 1819, when he exhibited his "The Raft of the Medusa" at the Paris Salon, that many art historians mark the beginning of the Romantic era in painting. Critics did not like the color palette, composition, and, most importantly, the subject matter of this work. The story of survival on a raft of people trying to escape from the sunken frigate "Medusa" off the coast of Senegal proved too heavy for the Salon regulars. Of the 147 people who boarded the raft, only 15 survived. It was a hellish ordeal: people fought for water and food, the strong pushed the weak overboard, the living ate the dead. Meanwhile, the captain and the governor sailed away in boats, cutting the tow ropes and leaving the raft to the mercy of the waves...

It was too dynamic, too vivid, too emotional, too shocking! Academicians harshly criticized the work, but a revolution in painting had already taken place: Géricault shook the foundations of classical painting and paved the way for a new direction.

Romanticism. Théodore Géricault. The Charging Chasseur, 1812

Romanticism. Théodore Géricault. The Charging Chasseur, 1812

Eugène Delacroix also waged battles with critics, becoming the leader of the French Romantic school. Recognition came to him only toward the end of his life. Delacroix was influenced by famous colorists of the Late Renaissance and Baroque, such as Titian, Veronese, and Rubens. He avidly read Shakespeare and Byron. He admired Géricault and boldly challenged high-society connoisseurs and the pillars of Academicism.

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. Pietà, 1842-1844

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. Pietà, 1842-1844

In 1824, Delacroix exhibited a painting at the Salon dedicated to the tragedy of the Greek people defending their independence from the Ottoman Empire. "Massacre at Chios" was received with a mix of enthusiasm and outrage. Poet Charles Pierre Baudelaire called the painting a "horrifying hymn to fate and suffering." Conservative critics were outraged by the "naturalism" in the presentation of the subject.

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. The Massacre at Chios, 1824

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. The Massacre at Chios, 1824

"Death of Sardanapalus" received no less negative reviews. Delacroix was accused of excessive cruelty, eroticism, and even blasphemy.

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. The Death of Sardanapalus, 1827

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. The Death of Sardanapalus, 1827

However, "Liberty Leading the People" (or "Liberty on the Barricades"), despite all its rebellious audacity, was embraced with enthusiasm. In 1830, a revolution erupted in France, and the artist, as they say, hit the right note. This painting was even purchased by the new government. Romanticism in the 1830s became a recognized artistic phenomenon.

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. Liberty Leading the People, 1830

Romanticism. Eugène Delacroix. Liberty Leading the People, 1830

The changing socio-political environment contributed to its victory:

- The circle of educated people expanded.

- The middle class gained strength.

- Historical traditions associated with monarchy were being shattered.

- The struggle against everything reactionary was underway.

- Freedom was proclaimed as one of the main values.

- Democratic tendencies were growing.

This was a time of bourgeois revolutions and national movements. Aristocratic ideals, celebrated in the Empire style, were replaced by ideals embraced by broader masses. The significance of individualism increased, and the importance of personality grew. All of this found reflection in the works of the masters of the Romantic school.

Romanticism. Thomas Phillips. Lord Byron in an Albanian dress, 1813

Romanticism. Thomas Phillips. Lord Byron in an Albanian dress, 1813

But it should not be assumed that Romantic painters were always in irreconcilable antagonism with classical traditions. Many masters combined Romanticism with Classicism in their work, and sometimes even with Academicism. This was particularly characteristic of Russia. For example, Karl Pavlovich Bryullov created a remarkable harmony between academic foundations and a romantic view of the world, producing a gallery of priceless masterpieces.

Great Romantic Artists

In addition to the aforementioned Romantic artists, it is essential to mention a few more outstanding creators of the era. In Spain, Francisco Goya was active as a painter.

Romanticism. Francisco Goya. The Nude Maja, 1797-1800

Romanticism. Francisco Goya. The Nude Maja, 1797-1800

His early work is characterized by a bright palette, but in the 1790s, during the era of the French Revolution, Goya's colors grew darker, and his themes became more tragic.

Romanticism. Francisco Goya. The birth of the Virgin Mary, 1774

Romanticism. Francisco Goya. The birth of the Virgin Mary, 1774

Especially poignant is the series "The Disasters of War," dedicated to the chaos and horror of the Napoleonic invasion. Figures are engulfed in darkness, lines are sharp, and strokes become scratches.

Romanticism. Francisco Goya. For what? (Disasters of War series, sheet 32), 1808-1814

Romanticism. Francisco Goya. For what? (Disasters of War series, sheet 32), 1808-1814

In Germany, Caspar David Friedrich worked in the Romantic tradition, and his creations leave an indelible mark on the soul: they convey a profound sense of solitude, despair, hopelessness, fate, and melancholy—all intertwined with poignant lyrical notes.

Romanticism. Caspar David Friedrich. The Sea of Ice, 1823–1824

Romanticism. Caspar David Friedrich. The Sea of Ice, 1823–1824

Frequently, the symphony of his paintings incorporates sounds of the nocturne; Friedrich often turned to a mystical and nocturnal ambiance.

Romanticism. Caspar David Friedrich. Crows in a tree, 1822

Romanticism. Caspar David Friedrich. Crows in a tree, 1822

Fine examples of German Romanticism are the melancholic and romantic landscapes of Karl Friedrich Lessing.

Romanticism. Karl Friedrich Lessing. Forest Chapel, 1839

Romanticism. Karl Friedrich Lessing. Forest Chapel, 1839

In Great Britain, John Constable painted romantic landscapes, and he had an incredible ability to depict weather phenomena—from downpours to rainbows. Contemporaries said that when you look at Constable's landscapes, you want to open an umbrella.

Romanticism. John Constable. Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, 1831

Romanticism. John Constable. Salisbury Cathedral from the Meadows, 1831

A recognized Romantic landscape artist was Joseph Mallord William Turner. Unfortunately, conservative colleagues could not fully appreciate Turner's talent. He was criticized for his unconventional style and the brightness of his colors.

Romanticism. William Turner. The Slave Ship, 1840

Romanticism. William Turner. The Slave Ship, 1840

However, history has set everything right: today, William Turner is a recognized figure in world painting, considered a precursor to the French Impressionists.

Romanticism. William Turner. The Grand Canal Venice, 1835

Romanticism. William Turner. The Grand Canal Venice, 1835

In Russia, in addition to Karl Pavlovich Bryullov, renowned portraitists Orest Adamovich Kiprensky and Vasily Andreevich Tropinin glorified the Romantic direction.

Romanticism. Orest Kiprensky. Portrait of Vassili Zhukovsky, 1815

Romanticism. Orest Kiprensky. Portrait of Vassili Zhukovsky, 1815

And, of course, among the famous Romantic landscape painters is Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky. He is considered one of the greatest marine artists on the planet.

Romanticism. Ivan Aivazovsky. Storm, 1868

Romanticism. Ivan Aivazovsky. Storm, 1868

Aivazovsky's marine landscapes are highly popular among collectors. In 2012, "View of Constantinople and the Bosphorus" fetched £3.2 million at a Sotheby's auction.

Postmodernism style in interior design - a game without rules

Postmodernism style in interior design - a game without rules  Peredvizhniki: Revolution in Russian Art of the 19th century

Peredvizhniki: Revolution in Russian Art of the 19th century  Antique arms and armour from all over the world

Antique arms and armour from all over the world  Kuznetsov porcelain

Kuznetsov porcelain  Albert Figdor Collection: Sweets for the ladies. Cigars for the gentlemen

Albert Figdor Collection: Sweets for the ladies. Cigars for the gentlemen  The painting "The Temptation of St. Anthony" by Hieronymus Bosch is a unique and mesmerizing work from the depths of centuries

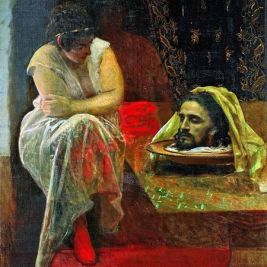

The painting "The Temptation of St. Anthony" by Hieronymus Bosch is a unique and mesmerizing work from the depths of centuries  The painting "Herodias" by Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoi is a moment of terrifying realization instead of the triumph of victory over the enemy

The painting "Herodias" by Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoi is a moment of terrifying realization instead of the triumph of victory over the enemy  Pastoral is an elegant and carefree genre of art from the Baroque and Rococo periods

Pastoral is an elegant and carefree genre of art from the Baroque and Rococo periods  Ethnic style in interior design - the romance of travel and exotic countries

Ethnic style in interior design - the romance of travel and exotic countries  Genre of Nude in Painting: Evolution and Historical Trends of the Nude Style

Genre of Nude in Painting: Evolution and Historical Trends of the Nude Style