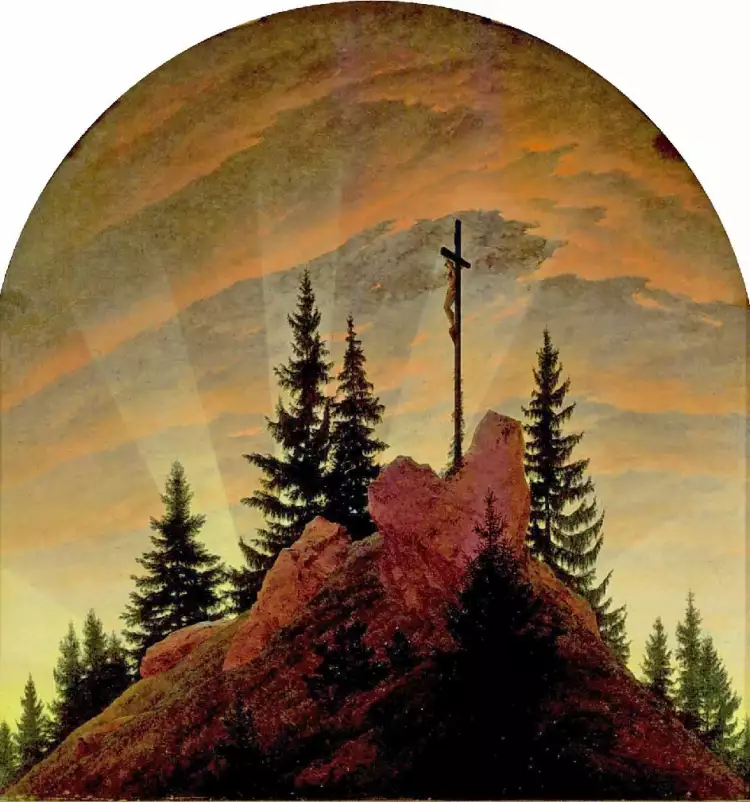

The painting "Cross in the Mountains" ("Tetschen Altar") by Caspar David Friedrich is an attempt to convey the presence of God through the elemental force of nature

"The Cross in the Mountains" ("Tetschen Altar") is a painting by Caspar David Friedrich, deviating from traditional iconography towards landscape. Unreal lighting gives a mystical meaning to the romantic depiction. Two light sources are positioned behind an impenetrable foreground. The viewer cannot see them, but brown stones, dark green silhouettes of trees, purple shadows, and gray sky in feathery clouds are all bathed in golden radiance.

What are these fading lamps? The upper part of the image provides an answer. The first is the setting sun. The second, from which five barely noticeable rays emanate, is likely the Creator. Towards Him is turned the cross entwined with ivy, unfolded three-quarters away from the viewer.

The Crucifixion lifted above the earth, according to the author's words, is an allegory whose meaning lies in the "demise of the wisdom of the old world." God has departed, and the earth without Him descends into darkness. Salvation for all remains in faith, which must be as strong as a rock and as unchanging as the evergreen fir needles, forever green in the scorching summer and harsh winter. The painting seems to reflect on the place of the image of Christ and His sacrifice in the life of every person.

Caspar David Friedrich. The painting The Cross in the Mountains (Tetschen Altar), 1808

Caspar David Friedrich. The painting The Cross in the Mountains (Tetschen Altar), 1808

- Title of the painting: "The Cross in the Mountains" (Tetschen Altar) (German: Das Kreuz im Gebirge (Tetschener Altar)).

- Artist: Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840).

- Year of creation: 1808.

- Size: 115 x 110.5 сm.

- Style: Romanticism.

- Genre: Landscape. Religious. Historical.

- Technique: Oil painting.

- Material: Canvas.

- Location: Gallery of New Masters, Dresden, Germany.

Caspar David Friedrich was a German artist of the late 18th to early 19th centuries, whose bold and innovative ideas sparked much controversy among art critics and enthusiasts. He supported the romantic direction of painting and sought to depict human helplessness against the backdrop of elemental forces of nature.

Caspar David Friedrich. Sketch of the Tetschen Altar, 1805-1807

Caspar David Friedrich. Sketch of the Tetschen Altar, 1805-1807

In order to achieve the correct perspective, Friedrich set up a replica of a throne in his studio, on which the painting would stand. One of the author's sketches testifies to this.

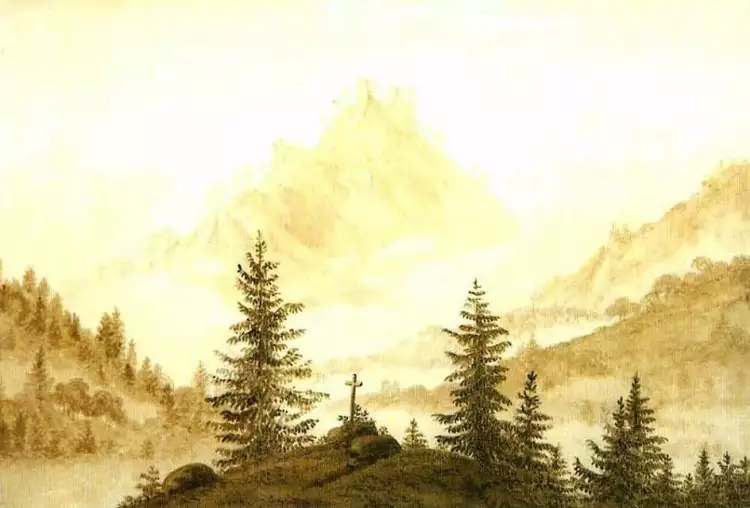

Caspar David Friedrich. Sketch Landscape, arrangement of the cross, 1804

Caspar David Friedrich. Sketch Landscape, arrangement of the cross, 1804

According to the surviving information, "The Cross in the Mountains" was not originally intended for a church. However, when Countess Theresia von Thun-Hohenstein saw the drawing, made in pencil and sepia, she fell in love with the image and commissioned the original for the Catholic chapel of her castle in Tetschen, Bohemia. Since then, the work has been known as the "Tetschen Altar".

Caspar David Friedrich. Drawing Tetschen Altar, 1805-1807

Caspar David Friedrich. Drawing Tetschen Altar, 1805-1807

According to other sources, numerous sketches and studies indicate that Friedrich conceived the full-scale oil painting much earlier.

Caspar David Friedrich. Sketch of the Cross, version, 1805

Caspar David Friedrich. Sketch of the Cross, version, 1805

Regardless of his intentions, the transformation of the idea can be traced through the surviving preparatory works. For the creation of the landscape, the master used sketches made from nature.

Caspar David Friedrich. Drawing View of the Elbe Valley, 1807

Caspar David Friedrich. Drawing View of the Elbe Valley, 1807

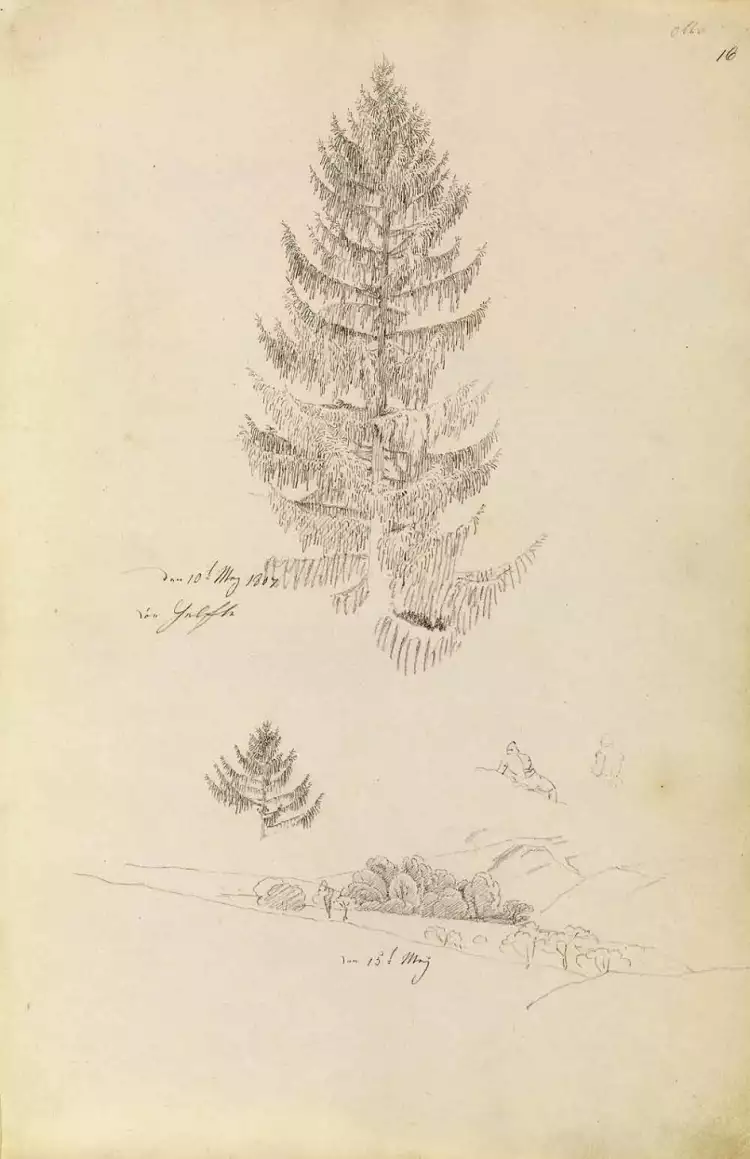

Although the trees in the final version are placed as if they are very far from the viewer to give them a recognizable appearance, Friedrich used sketches made from firs.

Caspar David Friedrich. Sketch The Tree, 1807

Caspar David Friedrich. Sketch The Tree, 1807

The frame with Christian symbolism was made by Christian Gottlieb Kühn. The author himself developed the design. A star crowns the arched top, beneath which are five cherubs. At the base, there is a triangle with the All-Seeing Eye, surrounded by sheaves of wheat and grapes, symbols of the Eucharist.

Caspar David Friedrich. The painting The Cross in the Mountains (Tetschen Altar), 1808

Caspar David Friedrich. The painting The Cross in the Mountains (Tetschen Altar), 1808

Controversy surrounding the altar panel did not cease even after the master's death. The work was criticized for its non-traditional approach and the very possibility of using landscape in altar painting was questioned. In the 20th century, the artist enjoyed great popularity in Nazi Germany. The Führer considered the painter's work to be an example of Aryan art.

Caspar David Friedrich's painting "The Cross in the Mountains" (also known as the "Tetschen Altar") was first presented to the public in 1808 and immediately attracted the attention of viewers. Executed in the artist's characteristic somber and detached manner, it conveys the author's vision of divine presence through a depiction of austere nature. The artwork is currently carefully preserved in the Galerie Neue Meister in Dresden, Germany.

Special auction Faussner collection

Special auction Faussner collection  The painting "Portrait of T. H. Shevchenko" by Ivan Kramskoy is a belief in humanity that has transcended centuries

The painting "Portrait of T. H. Shevchenko" by Ivan Kramskoy is a belief in humanity that has transcended centuries  The painting "Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)" by David Hockney is a cult work by the most influential contemporary artist

The painting "Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures)" by David Hockney is a cult work by the most influential contemporary artist  The top 10 most famous photographers in the world - the best photo artists of all time

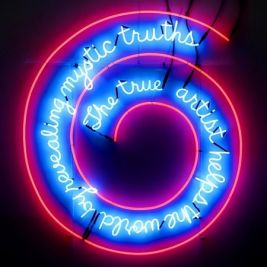

The top 10 most famous photographers in the world - the best photo artists of all time  Conceptualism is an art in which the idea is always more important than the form of the work: the essence, characteristics, history

Conceptualism is an art in which the idea is always more important than the form of the work: the essence, characteristics, history  Neoclassicism: once again, an alignment with ancient ideals!

Neoclassicism: once again, an alignment with ancient ideals!  French Artists of the 18th Century

French Artists of the 18th Century  Installation - the modern art of striking three-dimensional compositions

Installation - the modern art of striking three-dimensional compositions  The Order of St. Patrick is the most prestigious Irish distinction

The Order of St. Patrick is the most prestigious Irish distinction  Jazz Style in Interior Design - Creative Legacy of the "Roaring Twenties"

Jazz Style in Interior Design - Creative Legacy of the "Roaring Twenties"