Mathematicians Italy

Giovanni Alfonso Borelli was an Italian universalist scientist of the 17th century Scientific Revolution, the founder of biomechanics.

He studied mathematics under Benedetto Castelli (1577-1644) in Rome. In the 1640s Borelli was appointed to the chair of mathematics at the University of Messina and at Pisa in 1656. After 12 years at Pisa and numerous disputes with colleagues, Borelli left the university. In 1667 Borelli returned to the University of Messina, where he engaged in literary and historical studies, studied the eruption of the volcano Etna, and continued to work on the problem of muscular movement of animals and other bodily functions according to the laws of statics and dynamics. In 1674 he was accused of participating in a conspiracy to liberate Sicily from Spain and fled to Rome.

Borelli is known primarily for his attempts to explain muscular movement and other bodily functions according to the laws of statics and dynamics. His best-known work is De Motu Animalium (1680-81; "On the Motion of Animals"). Borelli calculated the forces required for balance in the various joints of the human body, long before Newton published his Laws of Motion. Borelli was the first to realize that musculoskeletal levers increase motion, not force, so muscles must produce much greater forces than those that resist motion. He was also one of the first microscopists: he made microscopic studies of blood circulation, nematodes, textile fibers, and spider eggs. Borelli also authored works on physics, medicine, astronomy, geology, mathematics, and mechanics.

Bonaventura Francesco Cavalieri (Latin: Bonaventura Cavalerius) was an Italian mathematician and a Jesuate. He is known for his work on the problems of optics and motion, work on indivisibles, the precursors of infinitesimal calculus, and the introduction of logarithms to Italy. Cavalieri's principle in geometry partially anticipated integral calculus.

Galileo Galilei was an Italian naturalist, physicist, mechanic, astronomer, philosopher, and mathematician.

Using his own improved telescopes, Galileo Galilei observed the movements of the Moon, Earth's satellites, and the stars, making several breakthrough discoveries in astronomy. He was the first to see craters on the Moon, discovered sunspots and the rings of Saturn, and traced the phases of Venus. Galileo was a consistent and convinced supporter of the teachings of Copernicus and the heliocentric system of the world, for which he was subjected to the trial of the Inquisition.

Galileo is considered the founder of experimental and theoretical physics. He is also one of the founders of the principle of relativity in classical mechanics. Overall, the scientist had such a significant impact on the science of his time that he cannot be overemphasized.

Athanasius Kircher was a German scholar, inventor, professor of mathematics and oriental studies, and a friar of the Jesuit order.

Kircher knew Greek and Hebrew, did scientific and humanities research in Germany, and was ordained in Mainz in 1628. During the Thirty Years' War he was forced to flee to Rome, where he remained for most of his life, serving as a kind of intellectual and information center for cultural and scientific information drawn not only from European sources but also from an extensive network of Jesuit missionaries. He was particularly interested in ancient Egypt and attempted to decipher hieroglyphics and other riddles. Kircher also compiled A Description of the Chinese Empire (1667), which was long one of the most influential books that shaped the European view of China.

A renowned polymath, Kircher conducted scholarly research in a variety of disciplines, including geography, astronomy, mathematics, languages, medicine, and music. He wrote some 44 books, and more than 2,000 of his manuscripts and letters have survived. He also assembled one of the first natural history collections.

Giovanni Vincenzo Petrini was an Italian priest and theologian, philosopher, mathematician, and expert in mineralogy.

Along with Scipio Breislacus, Petrini was one of the founders of Italian volcanology. He taught philosophy and mathematics, theology, but specialized in mineralogy and created the Mineralogical Cabinet in Nazareth. This museum was famous in Europe and was visited, among others, by Emperor Joseph II, who gave him rare specimens from the lands of the Empire and especially from Hungary.

Giovanni Petrini was the author of the catalog Gabinetto mineralogico del Collegio Nazareno ("The Mineralogical Cabinet of the Nazarene Collegium, described by external features and distributed by component parts" (Rome, 1791-1792). The specimens in it are classified according to a standard structure: salts, earths, bitumens, combustibles, and metals. There is also a section on gemstones.

Giuseppe Piazzi was an Italian astronomer, mathematician and priest.

Around 1764 Piazzi became a Theatine priest, in 1779 he was appointed professor of theology in Rome, and in 1780 - professor of higher mathematics at the Academy of Palermo. Later, with the assistance of the Viceroy of Sicily, he founded an observatory in Palermo. There he compiled his great catalog of the positions of 7,646 stars and showed that most stars move relative to the Sun. There, on January 1, 1801, Piazzi also discovered the asteroid Ceres.

Giuseppe Piazzi's merits were appreciated: he was a member of the Royal Society of London, a foreign honorary member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences and a foreign member of the Paris Academy of Sciences. A crater on the Moon is named in his honor.

Agostino Ramelli was an Italian military engineer and mechanic who worked in the fields of fortification and practical mechanics.

Ramelli studied mathematics, mechanics, and engineering under Giacomo di Marignano, who is considered a disciple of Leonardo da Vinci. He first showed his talents as a mechanic during Louis XIII's military campaign by constructing a mine under a bastion.

Ramelli invented many mechanisms that impressed his contemporaries, including their special aesthetic appeal. His most popular creation is the so-called Ramelli Book Wheel, a rotating reading table. Agostino Ramelli positioned his invention as a sleek design that allowed access to several books without having to get up from his seat.

Ramelli wrote and illustrated a book of engineering projects, Le various et artificiose machine ("Various and Artificial Machines"). The book contains 195 designs, over 100 of which are water-lifting machines, such as water pumps or wells, as well as bridges, mills, and so on. This very interesting book for our contemporaries is still published and is still in demand.

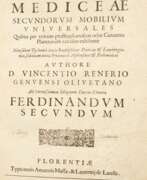

Vincenzo Renieri, born Giovanni Paolo, was an Italian priest, astronomer and mathematician.

Renieri was a member of the Olivetan Order and traveled throughout Italy. In 1633 in Siena, he met the already blind Galileo, who, appreciating his knowledge, instructed him to update his astronomical tables of the motion of the satellites of Jupiter, adding new ones. Rainieri later met the astronomer and scientist Vincenzo Viviani (1622-1703), with whom he worked for many years, continuing Galileo's observations of Jupiter's moons.

Renieri was also professor of mathematics at the University of Pisa and taught Greek there. In 1639 he published his work Tabulae Mediceae secundorum Mobilium Universales in Florence. One of the lunar craters is named after Renieri.

Paolo Ricci (Italian: Paolo Ricci, Latin: Paulus Ricius, German: Paul Ritz), also known as Ritz, Riccio, or Paulus Israelita, was a humanist convert from Judaism, a writer-theologian, Kabbalist, and physician.

After his baptism in 1505 he published his first work, Sol Federis, in which he affirmed his new faith and sought through Kabbalah to refute modern Judaism. In 1506 he moved to Pavia, Italy, where he became a lecturer in philosophy and medicine at the university and met Erasmus of Rotterdam. Ricci was also a learned astrologer, a professor of Hebrew, philosophy, theology, and Kabbalah, a profound connoisseur and translator of sacred texts into Latin and Hebrew, and the author of philosophical and theological works.

Paolo Ricci was a very prolific writer. His Latin translations, especially the translation of the Kabalistic work Shaare Orach, formed the basis of the Christian Kabbalah of the early 16th century.