Monks 17th century

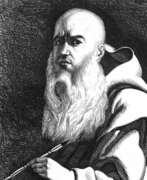

Abraham a Sancta Clara, real name Johann Ulrich Megerle, was an Augustinian monk and satirist, court preacher in Vienna.

Possessing an inimitable style of preaching that included folksy humor and harsh acrimony, Abraham was very popular with his contemporaries. He fearlessly scourged human vices, using both high pathos and puns, while conveying religious and moral messages. Some 600 of his recorded sermons on various subjects have survived.

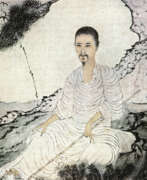

Joachim Bouvet was a French Jesuit monk and missionary who worked in China.

Joachim Bouvet was one of six Jesuit mathematicians chosen by Louis XIV to travel to China as his envoys and work as missionaries and scholars. In 1687 in Beijing, Bouvet began this work, especially in mathematics and astronomy, and in 1697 the Chinese emperor Kangxi (1654-1722) sent him as ambassador to the French king. Kangxi expressed his wish that Bouvet should bring more missionary scientists with him. Thus, in addition to his scholarly work, Bouvet was also an accomplished diplomat and served as a liaison between the Chinese Emperor Kangxi and King Louis XIV of France.

Bouvet brought to France a manuscript describing Kangxi's life with an eye for diplomatic subtleties, as well as a collection of drawings depicting graceful Chinese figures in traditional and ceremonial dress. The first French edition of The Historical Portrait of the Emperor of China was published in Paris in 1697, and was subsequently translated and published in other languages. And Bouvet returned to China in 1699 with ten new missionaries and a collection of King Louis XIV's engravings for Emperor Kangxi. He remained in China for the rest of his life.

Juana Inés de la Cruz or Juana of Asbaje, real name Juana Inés de Asbaje Ramírez de Santillananota, was a Mexican poet, scholar, and writer of the Latin American colonial period and the Spanish Baroque, and a Jerónimo nun.

Juana Ramírez was born into a poor family (Spanish father and Creole mother) and from an early age showed a burning thirst for knowledge and giftedness, but as a woman she was almost entirely self-taught. By her teens, she had already learned Greek logic and taught Latin to young children. She also learned Nahuatl, an Aztec language spoken in Central Mexico, and wrote several short poems in the language. At the age of 16, the girl was introduced to the court, and her intelligence impressed even Viceroy Antonio Sebastian de Toledo, Marquis de Mancera, and in 1664 he invited her to serve as maid of honor.

In 1669, at the age of 21, she took her tonsure at the Convent of Santa Paula of the Hieronymite Order in Mexico City, where she remained a recluse for the rest of her life. In the convent, Sister Juana enjoyed exceptional freedom: she continued to socialize with scholars and senior members of the court, amassed one of the largest private libraries in the New World, as well as a collection of musical and scientific instruments. Her plays in verse, poetry, and compositions for state and religious festivals were frequently and successfully performed at the palace.

Sister Juana was an outstanding representative of Spain's Golden Age: she was the last significant writer of the Latin American Baroque and the first great exponent of colonial Mexican culture. Sister Juana wrote sonnets, romances, and ballads, drawing on a vast store of classical, biblical, philosophical, and mythological sources. She also composed moral, satirical, and religious texts, as well as many poems praising courtiers, but she also defended women's right to education.

At the end of her life, due to pressure from religious dogmatists, Sister Juana had to sell her extensive library of some 4,000 volumes and return to strict reclusiveness. In 1695, the plague struck the convent and, while caring for her sisters, Juana died of the disease at about the age of forty-four.

Today, Juana Inés de la Cruz is a national icon of Mexico and Mexican identity as a prominent writer of the Spanish-American colonial period. The former convent where she lived is a center of higher education, and her image adorns Mexican currency.

Joaquim Juncosa was a Spanish Baroque painter and Carthusian monk, whose work left an indelible mark on the art world. Born in 1631 in Cornudella, Tarragona, Juncosa's talent emerged early, nurtured in a family of painters. By 1660, he had joined the Carthusian monastery of Scala Dei, propelling his career and solidifying his reputation as a preeminent painter of the Catalan Baroque.

Juncosa's skill was not confined to a single genre; he was adept at both portraits and frescoes. His works, primarily commissioned by monasteries and private residences, reflected a distinct Baroque style tempered with a unique restraint. This style may have been influenced by his time in Rome and his exposure to Roman painting trends. Unfortunately, much of his work at Scala Dei was destroyed in the Ecclesiastical confiscations of Mendizábal in 1835 and the Spanish Civil War in 1936.

Despite these losses, Juncosa's legacy endures. His remaining works, including the twelve canvases of "Mysteries of the Rosary" at the Carthusian monastery in Valldemossa, Majorca, and pieces preserved at the Sant Jordi Fine Arts Academy and Museo del Prado in Madrid, continue to captivate art enthusiasts and experts alike. His ability to convey depth and emotion through his art makes him a celebrated figure in the world of Baroque painting.

For collectors and art and antiques experts, Joaquim Juncosa's works offer a glimpse into the rich tapestry of Spanish Baroque art. His paintings not only showcase his technical prowess but also provide an insight into the cultural and religious milieu of his time. To stay updated on new product sales and auction events related to Juncosa, sign up for our updates. Rest assured, our subscription is purely informational, focusing on bringing you the latest in the art world.

Athanasius Kircher was a German scholar, inventor, professor of mathematics and oriental studies, and a friar of the Jesuit order.

Kircher knew Greek and Hebrew, did scientific and humanities research in Germany, and was ordained in Mainz in 1628. During the Thirty Years' War he was forced to flee to Rome, where he remained for most of his life, serving as a kind of intellectual and information center for cultural and scientific information drawn not only from European sources but also from an extensive network of Jesuit missionaries. He was particularly interested in ancient Egypt and attempted to decipher hieroglyphics and other riddles. Kircher also compiled A Description of the Chinese Empire (1667), which was long one of the most influential books that shaped the European view of China.

A renowned polymath, Kircher conducted scholarly research in a variety of disciplines, including geography, astronomy, mathematics, languages, medicine, and music. He wrote some 44 books, and more than 2,000 of his manuscripts and letters have survived. He also assembled one of the first natural history collections.

Chérubin of Orleans (French: Chérubin d'Orleans), born François or Michel Lasseré, was a French monk of the Order of the Friars Minor Capuchin, physicist, and optical instrument maker.

Cherubin was engaged in the study of optics and problems related to vision. He designed the first binocular telescope, as well as a special type of spectacle in which the lens was replaced by a short perforated tube. Many of his binoculars, binocular microscopes and telescopes survive today. Cheruben is also credited with modeling the eyeball to study the functioning of the ocular lens.

About his research and work, Cherubin of Orléans published in Paris the works La dioptrique oculaire (Dioptrique oculaire, 1671) and La vision parfaite (Perfect Vision, 1677).

Shitao or Shi Tao (simplified Chinese: 石涛; traditional Chinese: 石濤; pinyin: Shí Tāo; Wade–Giles: Shih-t'ao; other department Yuan Ji (Chinese: 原濟; Chinese: 原济; pinyin: Yuán Jì), born into the Ming dynasty imperial clan as Zhu Ruoji (朱若極), was a Chinese Buddhist monk, calligrapher, and landscape painter during the early Qing dynasty.