Mycologists 18th century

Caspar Commelin was a Dutch botanist and mycologist.

Caspar Commelin was trained as a medical doctor, practiced botanical science and worked on books that were left unfinished due to the death of his uncle, botanist Jan Commelin. Caspar was mainly interested in exotic plants.

Lewis David de Schweinitz (also Ludwig David von Schweinitz), born on February 13, 1780, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, was a German-American botanist and mycologist. His parents, Hans Christian Alexander and Dorothea Elizabeth von Watteville von Schweinitz, were instrumental in the administration of the Moravian Church in America. Following his early education in Bethlehem, Schweinitz was sent to Germany in 1798 to continue his academic pursuits.

In Germany, Schweinitz enrolled in the Moravian Theological Seminary at Niesky in Silesia. It was there that he met Professor Albertini, who shared his interest in botany. Schweinitz's focus on the study of fungi earned him the title "Father of North American Mycology." His contributions to the field were significant, as he was the first American to concentrate his botanical efforts specifically on fungi.

Among his many accomplishments, Schweinitz produced extensive mycological illustrations and published works on the subject. His manuscripts and watercolor paintings of fungi served as reference materials in the development of his Conspectus, a compendium of his findings and classifications. The impact of his work was so considerable that several taxa were named in his honor, highlighting his legacy in the world of botany and mycology.

Schweinitz passed away on February 8, 1834, but his legacy endures through his scientific contributions and the respect he garnered internationally as a botanist. His life and work continue to be celebrated and studied by those in the field, and his illustrations and findings remain a significant part of mycological history.

John Hill was a British botanist, pharmacologist and physician, geologist, writer and journalist.

Hill edited the monthly British Magazine for several years, and also wrote a daily society gossip column in The London Advertiser and Literary Gazette. His satirical, often on the edge of propriety articles were often the cause of scandals. Hill also wrote novels, plays, and scientific works on geology, medicine, philosophy, and botany.

In 1759, the first of the 26 volumes of his Plant System was published. This voluminous work contained descriptions of 26,000 different plants and 1,600 illustrations. For this long work, Hill received the Order of Vasa from the Swedish king and began calling himself Sir.

Jacob Christian Schäffer was a German inventor, naturalist, entomologist and mycologist.

Schäffer was a very versatile scientist. He is best known for his work in mycology (the study of fungi), but his most important publication was undoubtedly a book on daphnia or water fleas.

Schäffer also published reference books on pharmaceuticals and medicinal herbs. He conducted experiments on electricity, colors, and optics, and invented the manufacture of prisms and lenses. He invented the washing machine, designs for which he published in 1767, and studied ways to improve paper production.

Schäffer was a professor at the Universities of Wittenberg and Tübingen, a member of the Royal Society of London, and a correspondent of the French Academy of Sciences.

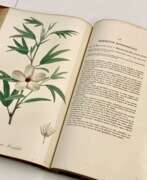

Etienne-Pierre Ventenat was a French botanist, mycologist and writer.

Etienne-Pierre Ventenat was one of the greatest botanists in France. Empress Josephine Bonaparte hired him to describe and catalog rare plants at her castle of Malmaison. Josephine enlisted eminent botanists such as Claes and Blaikie to collect plants on a grand scale. Ventenat was commissioned to write the text of the work on the Malmaison collection, and the illustrations were created by the talented artist Pierre-Joseph Redoute, nicknamed the "Raphael of Flowers." As a result, a sumptuous book entitled Jardin de la Malmaison (The Garden of Malmaison) was published in 1803.