ID 1362334

Lot 649 | The Yorktown Campaign as chronicled by the French navy

Estimate value

$ 80 000 – 120 000

March 1781 - June 1783

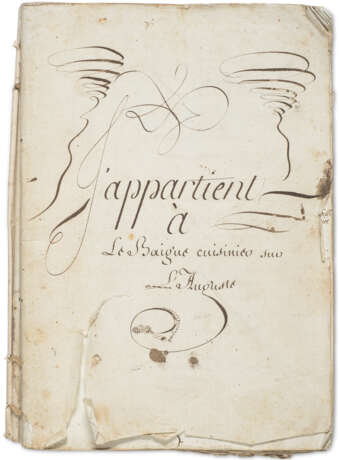

[BATTLE OF CHESAPEAKE CAPES AND THE SIEGE OF YORKTOWN]. Manuscript journal maintained by "Le Baigue," who served as "cuisinier" aboard the ship Auguste, various places including Martinique, Cap-Yorktown, 22 March 1781 - June 1783.

In French. 185 pages, 265 x 178mm with a 14 page manuscript bound in the center (title page torn, typical marginal wear throughout). String bound with wraps repurposed from several pages of a French genealogical directory.

Chronicling the most decisive battle of the American War of Independence.

An unpublished journal maintained aboard Louis Antoine de Bougainville's flagship Auguste, chronicling the campaigns of 1781 and 1782—including a first-hand account of the Battle of Chesapeake Capes and the Siege of Yorktown including a complete transcript of the Articles of Capitulation that paved the way for peace negotiations and British recognition of American independence, as well as copies of communications from Washington to De Grasse, as well as a mention of a post-surrender dinner with Washington, Cornwallis and De Grasse. The journal describes additionally the Battle of Port Royal (29 April 1781), as well as a detailed account of the Battle of the Saints (5 April 1782).

The journal opens with an account of the cuisiner's departure from Paris on 15 January 1781 with De Bougainville arriving in Brest on the 21st. On 13 March, the journalist and De Bougainville boarded the 80 gun Auguste which was in the final stages of preparation in the harbor. On the following page, the journalist lists the ships bound for America ("Noms des vaisseaux destinée pour L'Amérique"), together with the number of guns, respective commanders, and crew numbers. The ships of the line are listed in the order of combat beginning with the ships of the line composing White and Blue Division commanded by De Bougainville, the White Division commanded by De Grasse aboard the the flagship Ville de Paris, followed by the Blue Division, led by de Montiel.

From Europe to the Caribbean

The fleet departed Brest on 22 March 1781. Approaching Martinique in late April, they found the British blockading Fort Royal, and he describes the action in which De Grasse managed to draw out Samuel Hood's ships that allowed a French supply convoy to pass and relieve the island's garrison. In May, the fleet departed Martinique arriving at Tobago at month's end where the journalist had the opportunity to describe the island in great detail over several pages. From Tobago, the fleet touched at Grenada, returning to Martinique in June. From there, the fleet sailed to Saint-Dominque, headquarters France's Caribbean fleet at Cap-Haïtien ("Cap-François") arriving there on 15 July. For the next three weeks the fleet underwent preparations for sailing north to aid in operations in conjunction with Washington and Rochambeau. The journal records various boardings of additional troops for service in America including 50 members of the Metz Artillery (31 July) who were active in early French ground operations near Yorktown in advance the formal opening of the siege.

De Grasse's fleet departed Cap-Haïtien on 5 August, passing the coast of Cuba on the 17th before heading north through the Bahama Islands to conceal his movements, before arriving off Chesapeake Bay on the 31st. The next morning they began disembarking infantry and artillery that they had transported. Unbeknownst to the French, the squadron that Rodney had sent under Admiral Hood to chase De Grasse north, arrived in the same place three days before. When Hood could find no sign of the French Navy, he continued on to New York. De Grasse now controlled the entrance to the Chesapeake. When Hood and his 14 ships neared New York, he was met by an additional five ships under Graves, and the combined fleet sailed southward to engage De Grasse and free Cornwallis from his growing predicament arriving on the morning of 5 September.

The Battle of Chesapeake Capes

The morning of the 5th began somewhat inauspiciously for the French, according to our journalist, with the Auguste running aground on a sandbar, only to be freed by the rising tide. At 9 am patrol frigates spotted several sails in the west and "Monsieur de Bougainville immediately identified the man on lookout who reported that he indeed saw several sails." At first they assumed that the sails were those of a French supply convoy bound from Newport, Rhode Island to bring siege artillery to Yorktown, but within an hour they realized that it was British "squadron composed of 20 vessels not including the frigates" At that, "M. de Grasse made new signals to raise an anchor, and at 11 hours and a half he made the signal to let out the anchor cable … and set sail. The Commander signaled to close the line by order of speed, and to M. de Bougainville to pass at the head of the army and to always hold the wind. The ships The Pluton, le Marseillois, la Bourgogne, le Diadème and le Réfléchie were already far ahead of us. We followed them with St. Esprit which was behind us. The rest of the fleet ("armée") formed successively but far away from us. The English fleet was in the wind, at a standstill and formed in a line … The interval between us and the ships at the head and between St Esprit and the rest of the army gave space for the English vessels to take advantage of our disorder … and had the wind at their back. M. de Bougainville nevertheless held the wind as much as he could, and this maneuver put us at a quarter to three within rifle range." Despite that some troops that had been ashore were unable to board the ships in time before the fleet dropped anchor that morning, they used invalids in their place: "each one was at his post and impatiently awaited the order to fire, each one aspired only to the destruction of his enemy and showed great courage. The English who were at the head then held the wind to put themselves abeam of us … Two minutes after the ship that was across from us presented us his broadside we responded with ours. [Note: this is probably the HMS Terrible which had to be eventually scuttled]. The second that we did, the enemy took the wind to move farther away and win the wind’s advantage. Five others came at the same time towards us….Our ships at the rear joined us … and fired on the enemy’s ships that were closest in their range. At 5 and a quarter hours, after continuous fire for two hours and a half, our line found itself formed and pressed very close together. The enemy noticed that good order was beginning to reign in our fleet which gave us the advantage of being able to fire altogether and hold the wind together…"

The engagement concluded at sunset, and the journalist took stock of the day, noting that they "had the misfortune of having a dozen men killed in combat, including M. D’Orvan, major of the Division and lieutenant of the ship, who was taken by a cannonball that hit the gunwale on the forecastle next to M. de Bougainville, the same cannonball killed two sailors and a cabin boy. There were around ten men wounded more or less, many of whom died during the night and the next day. M. de la Salle, an officer of the Regiment de Brie, was wounded in his left foot and right hand by a cannonball that entered the second Batterie which, after losing some of its force hitting other places fell to pieces]. In addition to these accidents, we had a number of men burned by the fire from many shells to which the fire from other canons spread between the hands of the crew, seeing that they were leeward and stopped the fire within the ship. M. Augenne, an Gala officer, felt if only slightly the effects of the shells. We had a number of cannonball in the wood and the copper which did not cross through, our sails were completely riddled and a large part of the ropes cut."

For the next several days the two fleets sailed in line further to the southeast—away from the mouth of the Chesapeake. On 6 September, he wrote that they had suspected the British were "occupied repairing many of their ships which were lacking their topmasts and others their yardarms. At 11 o’clock, the wind having changed, M. de Grasse gave the signal for the army to tack." The next morning, they found the "wind was calm without being able to steer. The English fleet was far from us by two and a half hours. At 11 in the morning, the wind having picked up, the enemy found itself under the wind and as our line was not formed the General at 11¼ gave the signal to rally and get in order … and for the rest of the day we pursued the enemy who seeing that we had the wind’s advantage took great care to stay out of our range." On the 9th Hood set sail toward New York and De Grasse moved westward toward the Chesapekae after sighting another set of sails they were unable to identify. When they arrived there on the 11th, they found that Barras had arrived safely from Newport.("M. de Barras dans la baye de Chesapeak.") At that, as Mark Boatner observed, "Cornwallis' days were numbered."

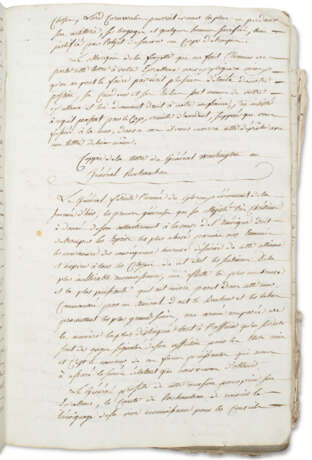

The next week was spent unloading siege equipment and using some ships to help ferry portions of Washington's and Rochambeau's army down the Chesapeake from Head of Elk. On the 25th, the fleet took formal positions to block the mouth of the bay, rather than take to the sea again to engage the British once again, now that news of reinforcements under Digby had arrived in New York. The journalist records a translation of Washington's 25 September letter that convinced De Grasse to remain in the Chesapeake, arguing that his departure, " by affording an opening for the succour of York, which the Enemy would instantly avail himself of—would frustrate these brilliant prospects—and the consequence would be not only the disgrace & loss of renouncing an enterprise upon which the fairest expectations of the Allies have been founded." It was a message delivered personally by Lafayette.

The journalist writes on the 25th, that "in the night a brig and a cutter came from the river to speak to the General. After a couple of hours, signals were given on board [?the army town] for all officers employed in the army to bord. At 11 o’clock in the morning, M. de Grasse signalled for all of the squadron to raise anchor and tack at peak. At two o’clock the Duc de Bourgogne gave signal to set sail. At half past two o’clock, the army was at sail with the heading N. ¼ N.W. to advance into the Bay," and anchored in a place "better positioned to see what was happening in the York River and the James." Over the next several days, the fleet settled in, preparing guards for the anchored ships, while enduring a hurricane on the night of the 29th. Another 800 troops disembarked from Barras' squadron on the 30th, and on the 1st they started transferring "bombs and mortars to the Camp," in small boats in the dark of night. After another storm on the 7th, the weather improved and they continued to continue their deliveries.

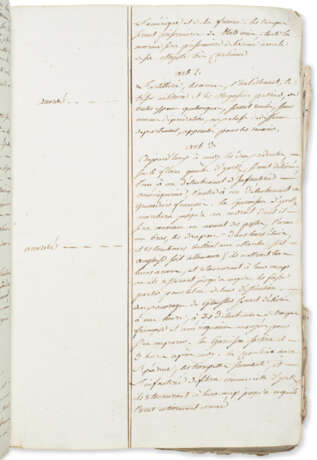

The Siege of Yorktown and Surrender

On the 10th, "we heard the noise from our land army’s battalion canons. From this we determined that it had begun to attack, and to fire on the town. The fire continued all day and all night." On the 11th, the first continued while a brig came "A brig came from the river which we hailed. It told us that the Valiant which was anchored at the entrance of the York River should enter the river as far as it could to ensure that none in the sieged town can find a means to disembark in boats and escape, and to cut off Cornwallis’ retreat to Carolina." On the 12th, "Our batteries performed with more veracity than the days before." But on the 17th, "At one o’clock in the morning there was a very violent hurricane, that forced the Experiment’s canoe to alight on our ship. We moored the canoe behind the ship but the waves were so strong that it sank half an hour later. Shortly after another canot passed along the ship but a little farther away that the tide carried it away. There was but one man in it. He thought that we could save him but as we had none of our boats in the water because they had been hoisted up when the storm began, we could not give him any help. The wind having calmed down we pulled the Experiment’s canot out of the water and it continued on its way. We heard shooting on the ground again but not as loudly as in the previous days."

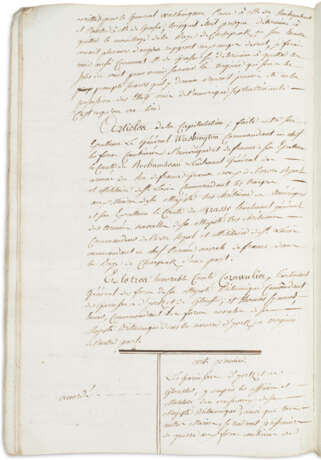

When the weather calmed the next day, "A boat came from the river that went to speak to the General. In fact news [?came] that the besieged had asked for a twenty-four hour ceasefire but they had been granted only two. At the end of four hours firing recommended on the town and they sent an envoy to ask for six more which were granted to them. Nevertheless, during the night some salvos were still heard." And then on the 19th, an "American boat came from the river to speak to the General [De Grasse]. Shortly after we sensed that Yorktown had capitulated and surrendered its arms with 1500 troupes taken prisoner and 1500 men from the Gloucester garrison. During the night all of the army’s ships hoisted up their stern and command flags in celebration." And the following day, he notes that "The crew was given a double ration in recognition of the capture." At this juncture, the journalist takes time to transcribe all fourteen articles of the surrender document ("Articles de la Capitulation, faite entre son Excellence Le Général Washington Commandant et chef les forces combinées de l'amerique et de france, son Excellence le Comte de Rochambeau Lieutenant Général des armée du Roi de france….") including fair copies of the signatures of Cornwallis and Washington.

After transcribing several other letters and newspaper transcripts, our diarist also observes that on the 21st, the day following the formal surrender ceremonies, "General Cornwallis, Governor of Yorktown, came to dine on board the Ville de Paris with Messrs. de Rochambeau and Washington. After dinner, seven or eight salutes were made [fired] in celebration of the capture. An envoy from Halifax came during the night bringing with him a number of French prisoners, soldiers and sailors sent back to us by the English. We embarked five of them on board."

On 28 October, "Around eleven o’clock our lookouts called out that they saw at the entrance to the Bay a squadron composed of 36 boats. It was not hard to believe that this was the English Squadron commanded by Admiral Digby which surely did not yet know of General Cornwallis’ surrender. M. de Grasse did not deem it necessary for the Squadron to set sail seeing that the reembarkation of our troops was not entirely finished and that the facilities that we had on the ground were not yet cleared away. Nevertheless he gave the signal to be ready to do so." Digby's relief expedition with 7,000 British reinforcements soon turned back to New York.

Epilogue

De Grasse's fleet soon returned to the Caribbean and spent the winter in operations in conjunction with the Spanish. From 9-12 April 1782, the journalist offers an equally detailed account of the Battle of the Saintes where Rodney prevailed, capturing De Grasse and his flagship. Fortunately the vanguard under De Bougainville managed to escape the British. The journal continues through the Auguste's return to Brest in 1783. At the center of the journal, an additional set of sheets have been bound in, the first listing the officers of the day during the Siege of Yorktown, a list documenting the strength of Rodney's fleet in April 1782, as well as lengthy descriptions of Martinique, St. Lucia, and St. Domingue.

The present journal is a wonderfully complete record of the most decisive naval campaign of the Revolutionary War—offering an alternative view of the Yorktown campaign from the navy that made the victory possible.

Although not fully translated, additional page images can be supplied on request.

| Artist: | George Washington (1732 - 1799) |

|---|---|

| Category: | Services |

| Auction house category: | Letters, documents and manuscripts, Books and manuscripts |

| Artist: | George Washington (1732 - 1799) |

|---|---|

| Category: | Services |

| Auction house category: | Letters, documents and manuscripts, Books and manuscripts |

| Address of auction |

CHRISTIE'S 20 Rockefeller Plaza 10020 New York USA | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preview |

| ||||||||||||||

| Phone | +1 212 636 2000 | ||||||||||||||

| Fax | +1 212 636 4930 | ||||||||||||||

| Conditions of purchase | Conditions of purchase | ||||||||||||||

| Shipping |

Postal service Courier service pickup by yourself | ||||||||||||||

| Payment methods |

Wire Transfer | ||||||||||||||

| Business hours | Business hours

|