Mathematicians Germany

Johann Hartmann Beyer was a German physician, mathematician and statesman.

He earned a master's degree in liberal arts at the University of Strasbourg, and then graduated from the University of Tübingen with a doctorate in medicine. In 1588 Beyer returned to his native Frankfurt and began working as a physician; a year later he was appointed Physicus ordinarius - his duties included overseeing the city's health care and pharmacy system.

In 1614 Beyer took up the position of senior burgomaster of Frankfurt, but during the Fetmilch Rebellion he became involved in conflict, was forced to resign and returned to science.

He had the richest library of scientific books, numbering about 2500 volumes, wrote scientific works on astronomy and mathematics, engaged in medical activity, having invented the famous Frankfurt pills. Beyer carried on a lively correspondence with scientists, including mathematician Johannes Kepler, dealing with decimal fractions. Beyer bequeathed his rich inheritance to the city and to charity.

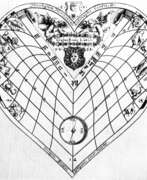

Georg Brentel the Younger was a German draftsman, engraver, and author of works on sundials and instrumentation.

He was the son of the cartographer Hans Brentel (1532-1614) and nephew of the armorial artist Georg Brentel the Elder (1525-1610). He always showed an interest in mathematics and astronomy, writing papers on these subjects and making instruments.

Brentel was particularly fond of designing sundials, and wrote several instructions for assembling various types of sundials - round and cubic, cross-shaped and heart-shaped.

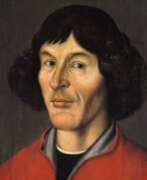

Nicolaus Copernicus (Polish: Mikołaj Kopernik) was a Polish and German scientist, astronomer, mathematician, mechanic, economist, and Renaissance canonist. He was the author of the heliocentric system of the world, which initiated the first scientific revolution.

Copernicus studied the humanities, including astronomy and astrology, at the University of Krakow and at the University of Bologna in Italy. Together with other astronomers, including Domenico Maria de Novara (1454-1504), he was engaged in observing the stars and planets, recording their movements and eclipses. At the time, medicine was closely related to astrology, as the stars were believed to influence the human body, and Copernicus also studied medicine at the University of Padua between 1501 and 1503.

Nicolaus Copernicus, based on his knowledge and observations, was the first to suggest that the Earth is a planet that not only revolves around the sun every year, but also rotates once a day on its axis. This was in the early 16th century when people believed the Earth to be the center of the universe. The scientist also suggested that the Earth's rotation explained the rising and setting of the Sun, the movement of the stars, and that the cycle of the seasons was caused by the Earth's rotation around itself. Finally, he correctly concluded that the Earth's motion in space causes the planets to move backwards across the night sky, the so-called retrograde direction.

Although Copernicus' model was not completely correct, it laid a solid foundation for future scientists, such as Galileo, who developed and improved mankind's understanding of the motion of celestial bodies. Copernicus completed the first manuscript of his book De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Rotation of the Celestial Spheres) in 1532. In it, the astronomer outlined his model of the solar system and the paths of the planets. However, he published the book only in 1543, just two months before his death, and dedicated it to Pope Paul III. Perhaps for this reason, and also because the subject matter was too difficult to understand, but the church did not finally ban the book until 1616.

Johann Dryander, born Johann Eichmann, was a German medical anatomist, mathematician and astrologer.

He studied anatomy and medicine at the University of Paris and the University of Erfurt, and in 1535 became professor of medicine at the University of Marburg. A year later, Dryander performed two public autopsies, making the first illustrated description of the dissection of the human brain. Dryander titled his book Anatomiae, hoc est, corporis humani dissectionis pars prior ("Anatomy, that is, the dissection of the human body, part one," suggesting a sequel, which, however, did not follow.

His work made a significant contribution to the development of modern anatomy. Toward the end of his life, Dryander also dabbled in astrology and mathematics.

Johannes Faulhaber was a German mathematician and fortification engineer.

He was a weaver, but studied mathematics and showed such aptitude that the city authorities appointed him the city mathematician and surveyor, a surveyor. In 1600, Faulhaber opened his own school in Ulm, and worked on the fortification of Basel, Frankfurt, and many other cities. He also designed water wheels in Ulm and made mathematical and geodetic instruments, particularly for military purposes.

Among the scientists with whom Faulhaber collaborated were Kepler and van Ceulen. He made the first German publication of Briggs' logarithms, and also made the first illustrated descriptions of Galileo's compass.

Georg Galgemair was a German mathematician and astrologer.

He was born into the family of the burgomaster of Donauwörth, was a pupil of Philip Apian, and then a master of mathematics at the University of Tübingen in 1585. After completing his studies, Galgemair began teaching at Lauingen in 1588.

His work on proportional circles led to the development of gnomonics. In the history of science, Galgemair is known for his works on mathematical instruments. As a calendar maker, he succeeded in 1606 in obtaining an imperial privilege for his calendars.

Johannes Kepler was a German mathematician and astronomer who discovered that the Earth and planets move around the Sun in elliptical orbits.

Kepler created the three fundamental laws of planetary motion. He also did seminal work in optics and geometry, calculated the most accurate astronomical tables, and made many inventions and discoveries in physics on which further scientific discoveries by advanced scientists were based.

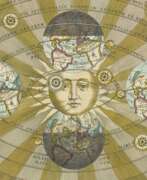

Athanasius Kircher was a German scholar, inventor, professor of mathematics and oriental studies, and a friar of the Jesuit order.

Kircher knew Greek and Hebrew, did scientific and humanities research in Germany, and was ordained in Mainz in 1628. During the Thirty Years' War he was forced to flee to Rome, where he remained for most of his life, serving as a kind of intellectual and information center for cultural and scientific information drawn not only from European sources but also from an extensive network of Jesuit missionaries. He was particularly interested in ancient Egypt and attempted to decipher hieroglyphics and other riddles. Kircher also compiled A Description of the Chinese Empire (1667), which was long one of the most influential books that shaped the European view of China.

A renowned polymath, Kircher conducted scholarly research in a variety of disciplines, including geography, astronomy, mathematics, languages, medicine, and music. He wrote some 44 books, and more than 2,000 of his manuscripts and letters have survived. He also assembled one of the first natural history collections.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was a German philosopher and a prominent polymath in many fields of science.

Leibniz was a universal genius; he showed his talents in logic, mathematics, mechanics, physics, law, history, diplomacy, and linguistics, and in each of the disciplines he has serious scientific achievements. As a philosopher, he was a leading exponent of 17th-century rationalism and idealism.

Leibniz was a tireless worker and the greatest scholar of his time. In the fate of Leibniz, among other things, there is one interesting page: in 1697, he accidentally met the Russian Tsar Peter I during his trip to Europe. Their further meetings led to the realization of several grandiose projects in Russia, one of which was the establishment of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was also the founder and first president of the Berlin Academy of Sciences and a member of the Royal Society of London.

Regiomontanus, real name Johannes Müller, was a 15th-century German astronomer and mathematician, one of the first printers.

The son of a miller, he entered the University of Leipzig at the age of 11 and later transferred to the University of Vienna. In 1452, Regiomontanus earned a bachelor's degree and then a master's degree. With his teacher, the mathematical astronomer Georg von Peyerbach (d. 1461), he spent the next years practicing astronomy and astrology, including observations of eclipses and comets, making astronomical instruments, and compiling horoscopes for the court of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III.

Regiomontanus was also seriously involved in mathematics, publishing his major work on trigonometry, On All Kinds of Triangles (1462-1464). From 1467 to 1471, Regiomontanus lived in Hungary as astrologer to Hungarian King Matyas I and Archbishop Janos Vitez. Then in Nuremberg, Germany, he opened an instrument workshop, established a printing house, and continued his planetary observations. The scholar planned to print extensive publications on classical, medieval, and modern mathematical sciences, but not all plans came to fruition.

Paolo Ricci (Italian: Paolo Ricci, Latin: Paulus Ricius, German: Paul Ritz), also known as Ritz, Riccio, or Paulus Israelita, was a humanist convert from Judaism, a writer-theologian, Kabbalist, and physician.

After his baptism in 1505 he published his first work, Sol Federis, in which he affirmed his new faith and sought through Kabbalah to refute modern Judaism. In 1506 he moved to Pavia, Italy, where he became a lecturer in philosophy and medicine at the university and met Erasmus of Rotterdam. Ricci was also a learned astrologer, a professor of Hebrew, philosophy, theology, and Kabbalah, a profound connoisseur and translator of sacred texts into Latin and Hebrew, and the author of philosophical and theological works.

Paolo Ricci was a very prolific writer. His Latin translations, especially the translation of the Kabalistic work Shaare Orach, formed the basis of the Christian Kabbalah of the early 16th century.

Johann Zahn (German: Johann or Johannes Zahn) was a German scientist and philosopher, optician and astronomer, mathematician and inventor.

Zahn studied mathematics and physics at the University of Würzburg, was professor of mathematics at the University of Würzburg, and served as a canon of the Order of Regular Canon Premonstratensians. His other activities were optics as well as astronomical observations.

In 1686 Johann Zahn invented and designed a portable camera obscura with fixed lenses and an adjustable mirror, which is the prototype of the camera. In his treatise on optics, Oculus Artificialis Teledioptricus (1702), Zahn gives a complete picture of the state of optical science of his time. He begins with basic information about the eye and then moves on to optical instruments. The book is aimed at eighteenth-century microscope and telescope enthusiasts and includes all the necessary details of construction, from lens grinding to drawings.