Scientists 17th century

Matthias Bernegger (latin: Bernegerus or Matthew) was an Austrian and French scientist, astronomer, mathematician, linguist and translator.

He was educated in Strasbourg, where he developed a special interest in astronomy and mathematics. Bernegger corresponded with the famous scientists Johannes Kepler and Wilhelm Schickard. From 1607, Bernegger taught at the Strasbourg Gymnasium, and in 1616 he was appointed professor at the Academy.

Bernegger is known for his translations of Justinian and Tacitus, and in 1612 translated into Latin Galileo's 1606 work on the proportional compass, adding considerably to it. These additional detailed annotations by Bernegger made Galileo's compass much easier to use, making it the first mechanical calculating device that could be applied to a wide variety of complex problems. In 1619 Bernegger prepared a three-volume manual of mathematics, and in 1635 he translated Galileo's Dialogue on the Two Mass Systems of the World.

Johann Hartmann Beyer was a German physician, mathematician and statesman.

He earned a master's degree in liberal arts at the University of Strasbourg, and then graduated from the University of Tübingen with a doctorate in medicine. In 1588 Beyer returned to his native Frankfurt and began working as a physician; a year later he was appointed Physicus ordinarius - his duties included overseeing the city's health care and pharmacy system.

In 1614 Beyer took up the position of senior burgomaster of Frankfurt, but during the Fetmilch Rebellion he became involved in conflict, was forced to resign and returned to science.

He had the richest library of scientific books, numbering about 2500 volumes, wrote scientific works on astronomy and mathematics, engaged in medical activity, having invented the famous Frankfurt pills. Beyer carried on a lively correspondence with scientists, including mathematician Johannes Kepler, dealing with decimal fractions. Beyer bequeathed his rich inheritance to the city and to charity.

Filippo Bonanni or Buonanni was an Italian Jesuit scholar. His many works included treatises on fields ranging from anatomy to music. He created the earliest practical illustrated guide for shell collectors in 1681, for which he is considered a founder of conchology. He also published a study of lacquer that has been of lasting value since his death.

Giovanni Alfonso Borelli was an Italian universalist scientist of the 17th century Scientific Revolution, the founder of biomechanics.

He studied mathematics under Benedetto Castelli (1577-1644) in Rome. In the 1640s Borelli was appointed to the chair of mathematics at the University of Messina and at Pisa in 1656. After 12 years at Pisa and numerous disputes with colleagues, Borelli left the university. In 1667 Borelli returned to the University of Messina, where he engaged in literary and historical studies, studied the eruption of the volcano Etna, and continued to work on the problem of muscular movement of animals and other bodily functions according to the laws of statics and dynamics. In 1674 he was accused of participating in a conspiracy to liberate Sicily from Spain and fled to Rome.

Borelli is known primarily for his attempts to explain muscular movement and other bodily functions according to the laws of statics and dynamics. His best-known work is De Motu Animalium (1680-81; "On the Motion of Animals"). Borelli calculated the forces required for balance in the various joints of the human body, long before Newton published his Laws of Motion. Borelli was the first to realize that musculoskeletal levers increase motion, not force, so muscles must produce much greater forces than those that resist motion. He was also one of the first microscopists: he made microscopic studies of blood circulation, nematodes, textile fibers, and spider eggs. Borelli also authored works on physics, medicine, astronomy, geology, mathematics, and mechanics.

Ismaël Boulliau (Boulliaud), also known as Ismael Bullialdus, was a French astronomer and mathematician who followed the teachings of Copernicus.

Boulliau worked as a librarian for many years and had the opportunity to study the scientific works of Copernicus, Galileo, and Kepler, and as a result became a strong supporter of the heliocentric system of the world. Boulliau was also intimately acquainted with Huygens, Gassendi, Pascal and other prominent scientists of the time, and he translated many works from Greek into Latin.

Boulliau's main astronomical work, published in 1645, was Astronomia philolaica (Astronomy of Philolaus, named after the ancient Greek Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus, who promoted the idea of the motion of the Earth). In it, he supported Kepler's first law that the planets move on ellipses, and provided new evidence for this. Isaac Newton, in Book III of The Mathematical Beginnings of Natural Philosophy, relies on measurements of the magnitudes of planetary orbits determined from observations by Kepler and Boulliau.

Boulliau was also interested in history, theology, classical studies, and philology. He was active in the Republic of Letters, an intellectual community whose members exchanged ideas.

Joachim Bouvet was a French Jesuit monk and missionary who worked in China.

Joachim Bouvet was one of six Jesuit mathematicians chosen by Louis XIV to travel to China as his envoys and work as missionaries and scholars. In 1687 in Beijing, Bouvet began this work, especially in mathematics and astronomy, and in 1697 the Chinese emperor Kangxi (1654-1722) sent him as ambassador to the French king. Kangxi expressed his wish that Bouvet should bring more missionary scientists with him. Thus, in addition to his scholarly work, Bouvet was also an accomplished diplomat and served as a liaison between the Chinese Emperor Kangxi and King Louis XIV of France.

Bouvet brought to France a manuscript describing Kangxi's life with an eye for diplomatic subtleties, as well as a collection of drawings depicting graceful Chinese figures in traditional and ceremonial dress. The first French edition of The Historical Portrait of the Emperor of China was published in Paris in 1697, and was subsequently translated and published in other languages. And Bouvet returned to China in 1699 with ten new missionaries and a collection of King Louis XIV's engravings for Emperor Kangxi. He remained in China for the rest of his life.

Tycho Brahe, born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, more commonly called Tycho, was a prominent Danish astronomer, astrologer, and alchemist of the Renaissance.

As a young man he traveled extensively throughout Europe, studying in Wittenberg, Rostock, Basel, and Augsburg and acquiring mathematical and astronomical instruments. In 1572 Tycho unexpectedly even for himself discovered a new star in Cassiopeia, and the publication of this turned the young Dane into an astronomer of European reputation. For further astronomical research he established an observatory and gathered around him modern progressive scientists.

Besides practicing astronomy, Tycho was an artist, scientist, and craftsman, and everything he undertook or surrounded himself with had to be innovative and beautiful. He even founded a printing house to produce and bind his manuscripts in his own way, and he perfected sanitary ware for convenience. His development of astronomical instruments and his work in measuring and fixing the positions of the stars laid a solid foundation for future discoveries.

Tycho's observations - the most accurate possible before the invention of the telescope - included a comprehensive study of the solar system and the precise positions of more than 777 fixed stars. What Tycho accomplished using only his simple instruments and intellect remains a remarkable achievement of the Renaissance.

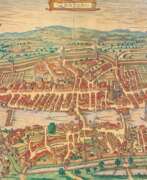

Georg Braun was a German topographical geographer, cartographer and publisher.

Braun was the editor-in-chief of the Civitates orbis terrarum, a groundbreaking atlas of cities, one of the major cartographic achievements of the 16th century. It was the first comprehensive and detailed atlas, with plans of the world's famous cities and bird's-eye views, and became one of the best-selling works of the time.

The book was prepared by Georg Braun in collaboration with the Flemish engraver and cartographer Frans Hoogenberg. Braun, as editor-in-chief, acquired tables, hired artists, and wrote the texts. They drew on existing maps as well as maps based on drawings by the Antwerp artist Joris Hofnagel and his son Jacob. Other authors include Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569), Jacob van Deventer (c. 1505-1575), and more than a hundred other artists and engravers.

Edward Browne was a British physician, president of the College of Physicians, traveler, historian and writer.

Edward was the eldest son of the famous British scientist Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682), received a Bachelor of Medicine degree from Cambridge later and a Doctor of Medicine degree from Oxford, and became a member of the Royal Society. In addition to medicine, his subjects of study included botany, literature, and theology. He lived in London and traveled throughout Europe visiting museums, churches, and libraries (Italy, France, the Netherlands, and Germany). In 1673 he published an account of his travels in Eastern Europe, notable for its scrupulous accuracy.

Edward Browne also published two other works: a historical treatise and biographies of Themistocles and Sertorius. He was physician to King Charles II of England and left many manuscript notes on medicine. The chronicle of his journey through Thessaly is a unique and valuable source of information about the region in the second half of the 17th century. He was admitted to the College of Physicians in 1675 and served as its president from 1704 to 1708.

Bonaventura Francesco Cavalieri (Latin: Bonaventura Cavalerius) was an Italian mathematician and a Jesuate. He is known for his work on the problems of optics and motion, work on indivisibles, the precursors of infinitesimal calculus, and the introduction of logarithms to Italy. Cavalieri's principle in geometry partially anticipated integral calculus.

Jan Commelin (Dutch: Jan Commelin or Jan Commelijn), also Johannes Commelin, was a Dutch botanist.

Jan Commelin is the son of the historian Isaac Commelin. He was a professor of botany and director of the Amsterdam Botanical Gardens. Jan Commelin wrote many scientific works on botany, notably compiling the first volume of descriptions of East and West Indian plants. The second volume was written by Jan's nephew, the botanist Caspar Kommelin, who expanded the earlier descriptions and added notes on African plants.

Caspar Commelin was a Dutch botanist and mycologist.

Caspar Commelin was trained as a medical doctor, practiced botanical science and worked on books that were left unfinished due to the death of his uncle, botanist Jan Commelin. Caspar was mainly interested in exotic plants.

Juana Inés de la Cruz or Juana of Asbaje, real name Juana Inés de Asbaje Ramírez de Santillananota, was a Mexican poet, scholar, and writer of the Latin American colonial period and the Spanish Baroque, and a Jerónimo nun.

Juana Ramírez was born into a poor family (Spanish father and Creole mother) and from an early age showed a burning thirst for knowledge and giftedness, but as a woman she was almost entirely self-taught. By her teens, she had already learned Greek logic and taught Latin to young children. She also learned Nahuatl, an Aztec language spoken in Central Mexico, and wrote several short poems in the language. At the age of 16, the girl was introduced to the court, and her intelligence impressed even Viceroy Antonio Sebastian de Toledo, Marquis de Mancera, and in 1664 he invited her to serve as maid of honor.

In 1669, at the age of 21, she took her tonsure at the Convent of Santa Paula of the Hieronymite Order in Mexico City, where she remained a recluse for the rest of her life. In the convent, Sister Juana enjoyed exceptional freedom: she continued to socialize with scholars and senior members of the court, amassed one of the largest private libraries in the New World, as well as a collection of musical and scientific instruments. Her plays in verse, poetry, and compositions for state and religious festivals were frequently and successfully performed at the palace.

Sister Juana was an outstanding representative of Spain's Golden Age: she was the last significant writer of the Latin American Baroque and the first great exponent of colonial Mexican culture. Sister Juana wrote sonnets, romances, and ballads, drawing on a vast store of classical, biblical, philosophical, and mythological sources. She also composed moral, satirical, and religious texts, as well as many poems praising courtiers, but she also defended women's right to education.

At the end of her life, due to pressure from religious dogmatists, Sister Juana had to sell her extensive library of some 4,000 volumes and return to strict reclusiveness. In 1695, the plague struck the convent and, while caring for her sisters, Juana died of the disease at about the age of forty-four.

Today, Juana Inés de la Cruz is a national icon of Mexico and Mexican identity as a prominent writer of the Spanish-American colonial period. The former convent where she lived is a center of higher education, and her image adorns Mexican currency.

René Descartes was a French philosopher, mathematician, and natural scientist who is considered the founder of modern philosophy.

Descartes was a very versatile scientist: besides numerous philosophical reflections, he wrote works on optics, meteorology and geometry. Contemporaries noted his extensive knowledge in many sciences. Descartes owns the famous saying "I think, therefore I exist" (best known in the Latin formulation "Cogito, ergo sum", although it was originally written in French: "Je pense, donc je suis").

He developed a metaphysical dualism that radically distinguished between mind, whose essence is thought, and matter, whose essence is extension in three dimensions. Descartes' metaphysics is rationalistic, based on the postulation of innate ideas of mind, matter, and God, but his physics and physiology, based on sense experience, are mechanistic and empirical.

Unlike his scientific predecessors, who felt a holy awe at the incomprehensibility of the divine essence of the universe, Descartes admired the ability of the human mind to understand the cosmos and to generate happiness itself, and rejected the view that human beings were inherently unhappy and sinful. He believed that it was inappropriate to pray to God to change the state of things and the world; it was much more productive to change oneself.

Denis Dodart was a French botanist, naturalist and physician.

Dodart studied at the University of Paris, received a doctorate in medicine and was already in his youth known for his erudition, eloquence and open-mindedness. In 1673 he was elected to the French Academy of Sciences.

He is known for his early studies of plant respiration and growth. Dodart collaborated with the French engraver Nicolas Robert to illustrate his botanical works.

Girolamo Fabrici d'Acquapendente, also known as Girolamo Fabrizio or Hieronymus Fabricius, was an Italian anatomist and surgeon and the founder of embryology. The Latinised form of his name, under which his works can be found, is Hieronymus Fabricius (ab Aquapendente).

Wilhelm Fabry von Hilden or Fabricius von Hilden (Latin: Fabricius Hildanus) was a German and Swiss Renaissance physician and surgeon, the founder of scientific surgery.

In 1576 he began a four-year apprenticeship as a surgeon with a barber in Neuss. Surgery at that time was considered the craft of bath and barbers; surgeons or wound doctors treated wounds, broken bones, inflammations, and many other ailments. After completing his apprenticeship, Fabry worked for five years as an assistant wound surgeon to Cosmas Slot (died 1585) at the court of Duke Wilhelm V in Düsseldorf. To expand his anatomical knowledge, Fabry constantly dissected and prepared cadavers. In later years, he also encouraged his students to do so and conducted public autopsies to draw attention to the importance of anatomical knowledge. He also made it a habit to do practice procedures on a cadaver before surgery.

In 1615 Fabry was appointed city physician of Bern. Here he wrote several books on gunshot wounds. In 1623 the versatile physician published a small book, "Christian and Good-Hearted Caution against Drunkenness," which he republished in more detail the following year under the title Christlicher Schlafftrunck. Fabry's most important surgical treatise was Observationem et curationem chirurgicam centuriae sex ("Six hundred surgical observations and cures"), first published in 1606. This compilation remained the most important book of German surgery until Lorenz Heister. It describes new surgical methods and surgical instruments for the treatment of amputations, nasal polyps, bladder stones, dropsy, hernias, ascites, etc., etc., etc.

For centuries, Fabricius remained one of the most respected surgeons not only in Germany and Switzerland, but throughout Europe. Among his many accomplishments in the field of surgery may be enumerated his innovation in the amputation of the thigh, for which he invented a special tourniquet; the excision of involved axillary glands in breast cancer; the first classification of burns into three degrees with the appropriate treatment for each variety; and the first description of a medical field chest for military purposes.

Although in his later years Fabritius had already given up practicing medicine, he continued to write medical papers and maintain an active scientific correspondence until his death. He authored some 20 medical books. It was his surgical works, translated into German, French, Latin, English and Dutch, that ensured his recognition centuries later.

Giovanni Battista Ferrari was an Italian Jesuit scholar, professor of Oriental languages and botanist.

Giovanni Ferrari had linguistic abilities and at the age of 21 knew Hebrew well, spoke and wrote Greek and Latin perfectly, and learned Syriac. He became professor of Hebrew and rhetoric at the Jesuit College in Rome and edited a Syriac-Latin dictionary in 1622.

Ferrari always showed great interest in the systematics and classification of fruits. He was appointed head of the chair of Hebraistics at the College of Rome and held this position for 28 years. In 1623, Ferrari became horticultural advisor to the family of Pope Urban VIII at the Palazzo Barberini, which soon became famous for its rare plants, including orange trees. Ferrari later wrote the first book on citrus trees, equating them to the mythical golden apples of the Hesperides conquered by Hercules. Orange trees became an important element of Baroque gardens, symbolizing the rewards earned by the magnanimous prince. The scientist also described the medicinal properties of citrus fruits.

In 1633, the first treatise on floriculture, De florum cultura, was published. In it, Ferrari describes garden layout with contemporary examples, flower specimens and their cultivation, and general horticulture.

Galileo Galilei was an Italian naturalist, physicist, mechanic, astronomer, philosopher, and mathematician.

Using his own improved telescopes, Galileo Galilei observed the movements of the Moon, Earth's satellites, and the stars, making several breakthrough discoveries in astronomy. He was the first to see craters on the Moon, discovered sunspots and the rings of Saturn, and traced the phases of Venus. Galileo was a consistent and convinced supporter of the teachings of Copernicus and the heliocentric system of the world, for which he was subjected to the trial of the Inquisition.

Galileo is considered the founder of experimental and theoretical physics. He is also one of the founders of the principle of relativity in classical mechanics. Overall, the scientist had such a significant impact on the science of his time that he cannot be overemphasized.

William Gilbert was a British physicist and medical scientist famous for pioneering the study of magnetic and electrical phenomena.

After receiving a medical degree, Gilbert settled in London and began his research. In his major work De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure (On Magnetic Stones and Magnetic Bodies and the Great Magnet of the Earth), published in 1600, the scientist describes in detail his studies of magnetic bodies and electric attraction.

After years of experimentation, he came to the conclusion that the compass arrow points north-south and downward because the Earth acts as a rod magnet. He was the first to use the terms electric attraction, electric force, and magnetic pole. Gilbert came to believe that the Earth rotates on its axis and that the fixed stars are not all the same distance from the Earth, and believed that the planets are held in their orbits by magnetism.

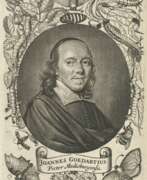

Johannes Goedaert was a Dutch naturalist, entomologist and artist.

Goedaert was one of the authors on entomology and the first to write about insects in the Netherlands and Europe, based on his own observations and experiments between 1635 and 1667. In 1660, Goedaert published the first of three volumes collectively titled Metamorphoses and History of Nature, the last volume appearing in 1669.

Goedaert's work is valuable in that for the first time he used his own drawings instead of woodcuts to illustrate his insects, and they are of noticeably higher quality than those in Moffett's volume. Goedaert was a talented and observant artist and draughtsman, and he used magnifying glasses but preferred to draw insects at life-size. The book depicts detailed phases of insect growth, including their metamorphosis. The scientist not only described the process of their development, but also described and sketched the various stages that insects go through during their life cycle.

William Howe or How was a British botanist and physician.

He studied at St. John's College, Oxford, earning a bachelor's degree and then a master's degree in medicine. He served briefly in the King's army as a cavalry commander, and later returned to the medical profession and practiced in London.

In his Phytologia Britannica, natales exhibens Indigenarum stirpium sponte Emergentium ("Phytology Britannica"), published in London in 1650, William Howe combined Thomas Johnson's catalogs into a single alphabetical list, supplemented with additional plants from other sources. This was the first edition of the book to compile for the first time all the known plants of Britain with descriptions of their occurrence.

Christiaan Huygens van Zeelhem was a Dutch mechanic, physicist, mathematician, inventor and astronomer who formulated the wave theory of light.

An admirer of Descartes, Huygens preferred to conduct new experiments himself to observe and formulate laws. In physics, he contributed to the development of the crucial Huygens-Fresnel principle, which applies to wave propagation. He also extensively investigated free fall. He experimentally proved the law of conservation of momentum. He derived the law of centrifugal force for uniform circular motion.

He also invented the pendulum clock, discovered centrifugal force and the true shape of Saturn's rings as well as its moon Titan. Huygens is considered the first theoretical physicist to use formulas in physics and one of the founders of theoretical mechanics and probability theory.

Athanasius Kircher was a German scholar, inventor, professor of mathematics and oriental studies, and a friar of the Jesuit order.

Kircher knew Greek and Hebrew, did scientific and humanities research in Germany, and was ordained in Mainz in 1628. During the Thirty Years' War he was forced to flee to Rome, where he remained for most of his life, serving as a kind of intellectual and information center for cultural and scientific information drawn not only from European sources but also from an extensive network of Jesuit missionaries. He was particularly interested in ancient Egypt and attempted to decipher hieroglyphics and other riddles. Kircher also compiled A Description of the Chinese Empire (1667), which was long one of the most influential books that shaped the European view of China.

A renowned polymath, Kircher conducted scholarly research in a variety of disciplines, including geography, astronomy, mathematics, languages, medicine, and music. He wrote some 44 books, and more than 2,000 of his manuscripts and letters have survived. He also assembled one of the first natural history collections.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was a German philosopher and a prominent polymath in many fields of science.

Leibniz was a universal genius; he showed his talents in logic, mathematics, mechanics, physics, law, history, diplomacy, and linguistics, and in each of the disciplines he has serious scientific achievements. As a philosopher, he was a leading exponent of 17th-century rationalism and idealism.

Leibniz was a tireless worker and the greatest scholar of his time. In the fate of Leibniz, among other things, there is one interesting page: in 1697, he accidentally met the Russian Tsar Peter I during his trip to Europe. Their further meetings led to the realization of several grandiose projects in Russia, one of which was the establishment of the Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was also the founder and first president of the Berlin Academy of Sciences and a member of the Royal Society of London.

Fortunio Liceti (Latin: Fortunius Licetus) was an Italian physician, natural philosopher, writer and educator.

Liceti studied philosophy and medicine at the University of Bologna and earned doctorates in these disciplines. He taught logic and philosophy at the University of Pisa, and became professor of philosophy at the University of Padua and the University of Bologna. At the University of Padua, Liceti became friends with Galileo Galilei.

Liceti's inquisitive mind was interested in a wide range of subjects: from genetics and reproduction to gems and animals. In general, Fortunio Liceti was a very industrious and prolific scientist: he published a book each year, writing more than seventy works on a wide range of subjects, including the human soul, reproduction, and birth defects.

In 1616, Liceti wrote and published the first edition of De monstruorum causis, natura et differentiis (On the Causes, Nature, and Differences of Monsters), a chronologically ordered catalog of monsters from antiquity to the seventeenth century. Among these monsters were infants with congenital malformations. Liceti was one of the first scholars to attempt to systematically categorize birth defects according to their causes, including numerous causes not related to the supernatural. This topic interested the scientist greatly and he returned to it several times during his life, supplementing it with illustrations, among other things. From 1640 to 1650. Liceti also wrote and published seven different volumes in which he answered questions from famous people on a wide variety of medical topics.

Martin Lister was a British naturalist and physician.

It could be argued that Lister founded two fields of natural history: arachnology (the study of spiders) and conchology (the study of the shells of organisms). He wrote more than 60 articles in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, published several volumes on natural history, speculated on the mysterious nature of fossils, and was successful as a physician.

Lister employed his artist daughters to illustrate his books on insects and molluscs - the names of Susanna and Anne appear on the title pages of the volumes. The Lister family published Historiæ Conchyliorum between 1685 and 1692.

Marcello Malpighi was an Italian biologist, anatomist and physician, professor of logic, theoretical and practical medicine, and a member of the Royal Society of London.

After graduating from the University of Bologna with the degree of Doctor of Medicine and Philosophy, Malpighi soon took up a professorship there, then taught at the universities of Pisa and Messina. At the same time as teaching, he conducted biological research with his microscopes, which was an innovation in those days. In 1661, he identified and described the pulmonary and capillary network connecting small arteries to small veins, one of the most important discoveries in the history of science. He also isolated taste buds and regarded them as nerve endings, described the minute structure of the brain, the optic nerve, and in 1666 was the first to see red blood cells and attribute to them the color of blood. His treatise De polypo cordis (1666) explained the composition of blood and how it coagulates.

During his medical practice, Malpighi studied microscopic sections of the liver, brain, spleen, kidneys, and the bone and deep layers of skin that now bear his name. In his landmark 1673 work on the embryology of the chicken, the scientist concluded that the embryo forms in the egg after fertilization. In 1675-79 he also made extensive comparative studies of the microscopic anatomy of several different plants and saw analogies between plant and animal organisms. The Royal Society of London published two volumes of his botanical and zoological works in 1675 and 1679. His Anatome Plantarum is richly decorated with engravings by Robert White.

After his house was burned and looted by his adversaries, in 1691 Pope Innocent XII invited him to Rome as papal personal physician, which was a great honor.

Malpighi can be considered the first histologist. For almost 40 years he used the microscope to describe the main types of plant and animal structures and thus marked for future generations of biologists the main directions of research in botany, embryology, human anatomy and pathology. The conflict between ancient ideas and modern discoveries continued throughout the seventeenth century. Malpighi was convinced that microscopic anatomy, by showing the minute structure of living things, questioned the value of the old medicine. He laid the anatomical foundation for the subsequent understanding of human physiological exchanges.

Christopher Merrett was a British physician and natural scientist.

Merrett was somewhat of a polymath and natural philosopher. His interests ranged from coinage and tin mining in Cornwall to glassblowing and butterfly taxonomy (his Pinax Rerum Naturalium Britannicarum of 1666 is now recognized as the earliest complete list of birds and butterflies in England).

However, he is much better known today as the first Englishman to record the existence of the sparkling wine phenomenon. It was Christopher Merrett in 1662 who first documented the existence of bubbles in an alcoholic beverage. He described the fundamental winemaking technique that was later called the "method of champanization" and perfected the production of stronger glass in the manufacture of wine fermentation bottles, which had previously exploded easily.

Thomas Moffet was a British naturalist-naturalist and physician.

After receiving his MD degree in 1580, Thomas Moffet studied the anatomy of the mulberry silkworm in Italy, then returned to England to study arthropods in general, especially spiders. He edited and expanded the work Insectorum sive Minimorum Animalium Theatrum ("Insect Theater"), an illustrated guide to the classification and life of insects.

Moffet was also an ardent supporter of the Paracelsian system of medicine.

Isaac Newton was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the greatest mathematicians and physicists and among the most influential scientists of all time. He was a key figure in the philosophical revolution known as the Enlightenment. His book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), first published in 1687, established classical mechanics. Newton also made seminal contributions to optics, and shares credit with German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz for developing infinitesimal calculus.

In the Principia, Newton formulated the laws of motion and universal gravitation that formed the dominant scientific viewpoint until it was superseded by the theory of relativity. Newton used his mathematical description of gravity to derive Kepler's laws of planetary motion, account for tides, the trajectories of comets, the precession of the equinoxes and other phenomena, eradicating doubt about the Solar System's heliocentricity. He demonstrated that the motion of objects on Earth and celestial bodies could be accounted for by the same principles. Newton's inference that the Earth is an oblate spheroid was later confirmed by the geodetic measurements of Maupertuis, La Condamine, and others, convincing most European scientists of the superiority of Newtonian mechanics over earlier systems.

Chérubin of Orleans (French: Chérubin d'Orleans), born François or Michel Lasseré, was a French monk of the Order of the Friars Minor Capuchin, physicist, and optical instrument maker.

Cherubin was engaged in the study of optics and problems related to vision. He designed the first binocular telescope, as well as a special type of spectacle in which the lens was replaced by a short perforated tube. Many of his binoculars, binocular microscopes and telescopes survive today. Cheruben is also credited with modeling the eyeball to study the functioning of the ocular lens.

About his research and work, Cherubin of Orléans published in Paris the works La dioptrique oculaire (Dioptrique oculaire, 1671) and La vision parfaite (Perfect Vision, 1677).

John Ray was a British clergyman, naturalist, botanist and zoologist, and a Fellow of the Royal Society of London.

He came from a poor family, but through his persistence in acquiring knowledge he achieved recognition as a scientist. Ray published important works on botany, zoology, and natural history. His classification of plants in Historia Plantarum was an important step toward modern taxonomy (the scientific study of naming, defining, and classifying groups of biological organisms based on common characteristics). John Ray was the first to provide a biological definition of the term "species."

Jean Rey was a French chemist and physician.

Rey received a Master of Arts degree from the Academy of Montauban, then a doctorate from the University of Montpellier, and worked as a physician in his hometown of Le Bug. He was also engaged in chemical research, corresponded with R. Descartes, M. Mersenne and others.

Jean Rey was the first to express the idea of conservation of mass as applied to chemical reactions. While conducting experiments in his brother's forge, he discovered that the mass of lead and tin increases with calcination. The researcher explained this based on the assumption that air has mass and that lead and tin combine with air during calcination. In 1630 Rey published a treatise on this topic, "Experiments to find the reasons for the increase in the weight of tin and lead during calcination". As can be seen from the treatise, he realized that substances are made up of particles. His discovery of the weight of air also made possible the invention of the Torricelli barometer in 1643. Jean Rey also developed a device called the thermoscope, a precursor to the thermometer.

Johann Jakob Scheuchzer was a Swiss naturalist and geologist, paleontologist and fossil collector.

Scheuchzer studied at the University of Altdorf near Nuremberg, earned a doctorate in medicine at Utrecht University, and studied astronomy. He worked as a teacher, physician, and corresponded extensively with many scientists, writing several papers, including those on Swiss research, weather, geology, and fossils. Scheuchzer collected fossils during his extensive travels. And, as a proponent of diluvialism, he believed that all fossils and layers of the earth were formed by the Flood.

Between 1731 and 1735, Scheuchzer published a massive four-volume work called Physica Sacra, which is essentially a commentary on the Bible. It presented the facts of natural history along with passages of scripture. Thus Physcia Sacra attempted to reconcile the Bible with science.

This book is also called the "Copper Bible" because it contains over 750 magnificent color engravings on copper plates. These engravings are in themselves the pinnacle of engraving from the Baroque period. The illustrations depict scenes with biblical and scientific motifs. They were based on his own cabinet of natural history and other famous European cabinets of rare specimens. The engravings were produced by highly skilled engravers, including Georg Daniel Heumann and Johann August Corwin.

During his lifetime, Johann Jakob Scheuchzer wrote 34 scientific papers and many articles, and he was a member of the Royal Society.

Marco Aurelio Severino was an Italian surgeon, anatomist and zoologist, one of the founders of comparative anatomy.

From childhood Severino studied Latin, Greek, rhetoric, poetry and law in various schools in Calabria, then continued his studies in Naples, soon moving from law to medicine. In Naples he met Tommaso Campanella, who had a great influence on the formation of his worldview. After receiving a medical degree in Salerno in 1606, he studied surgery in Naples with Giulio Jasolino. In 1615 Severino was appointed the first surgeon at Ospedale degli Incurabili. Severino made significant contributions to the transformation of naturophilosophy, medical and surgical practice, to which much of his printed work is devoted.

Severino's main contribution, however, lies in his anatomical works, especially the Zootomia Democritea. This work may be called the earliest comprehensive treatise on comparative anatomy. Severino is considered one of the pioneers of comparative anatomy.

Severino's cultural interests extended far beyond medicine. He corresponded with many prominent physicians and scientists of his time, including William Harvey and John Houghton in England, Thomas Bartolin and Ole Worm in Denmark, J.G. Volkamer and Johannes Wesling in Germany, and Campanella, Jasolino, and Tommaso Cornelio in Italy. Severino was tried by the Inquisition for allegedly unorthodox religious and philosophical views, but was eventually acquitted. He died of the plague in Naples.

Jan Swammerdam was a Dutch naturalist and biologist, anatomist and microscopist.

Swammerdam graduated from the Faculty of Medicine at Leiden University, then studied in Paris, earning a doctorate in medicine, and devoted himself exclusively to microscopic research. He used a single-lens microscope to study insect anatomy, and accurately described and illustrated the life history and anatomy of many species. His observations of their development allowed him to divide insects into four major divisions according to the degree and type of metamorphosis. His greatest contribution to biology was to understand insect development and to demonstrate that the same organism persists through different stages.

Jan Swammerdam wrote a voluminous work entitled A General History of Insects (1669) and The Bible of Nature (1737-1738), one of the finest collections of microscopic observations ever published. Considered the most accurate of the classical microscopists, he was the first to observe and describe erythrocytes in 1658.

Swammerdam was also a recognized anatomist: in 1670 he was granted the privilege of dissecting human bodies in Amsterdam, which at the time required a special license available only to a limited number of researchers. He developed a new dissection technique and also designed several new instruments.

Antonio Vallisneri the Elder was an Italian naturalist, physician and geologist, collector, and member of the Royal Society of London.

He studied in Bologna, Venice, Padua and Parma and headed the chair first of practical medicine and then of theoretical medicine at the University of Padua. In addition to medicine, Vallisneri conducted important research in the natural sciences. In particular, in the field of geology, he is credited with recognizing the organic nature of fossils unrelated to the Great Flood, which contributed to the end of centuries-old disputes. His observations on the water cycle, thermal waters and some mines in the Apennines were also important.

Vallisneri was interested in all branches of the natural sciences, collecting numerous collections of animals, minerals, and other natural objects during his lifetime. The scientist compiled a brief catalog of his collection, which was published in 1733 by his son, Antonio Vallisneri, Jr. The Vallisneri Museum included naturalistic finds, anatomical preparations, medical and scientific instruments, antiques, and exotics from various cultures and eras as well as geographical origins. In 1734, his son donated this museum to the University of Padua, initiating the creation of a general museum for the university.

Antonio Vallisneri Jr. followed in his father's footsteps and for many years held the position of professor of natural history at the University of Padua. He devoted his life to collecting and processing his father's writings and tidying up his library, which contained about a thousand volumes. These were donated to the University Library in Padua.

Otto Guericke, from 1666 von Guericke (pronunciation and original spelling: Gericke) was a German politician, jurist, physicist and inventor. He is best known for his experiments on air pressure with the Magdeburg hemispheres. He is considered the founder of vacuum technology.

Johann Zahn (German: Johann or Johannes Zahn) was a German scientist and philosopher, optician and astronomer, mathematician and inventor.

Zahn studied mathematics and physics at the University of Würzburg, was professor of mathematics at the University of Würzburg, and served as a canon of the Order of Regular Canon Premonstratensians. His other activities were optics as well as astronomical observations.

In 1686 Johann Zahn invented and designed a portable camera obscura with fixed lenses and an adjustable mirror, which is the prototype of the camera. In his treatise on optics, Oculus Artificialis Teledioptricus (1702), Zahn gives a complete picture of the state of optical science of his time. He begins with basic information about the eye and then moves on to optical instruments. The book is aimed at eighteenth-century microscope and telescope enthusiasts and includes all the necessary details of construction, from lens grinding to drawings.