ID 1109038

Lot 238 | Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Valeur estimée

£ 9 000 – 12 000

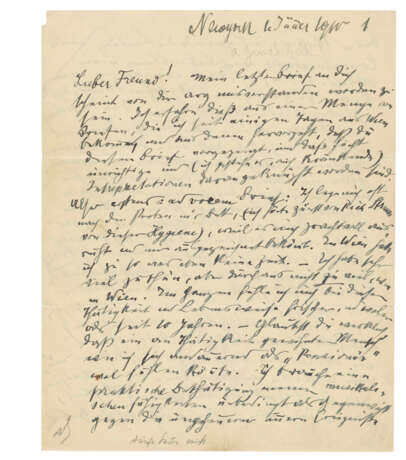

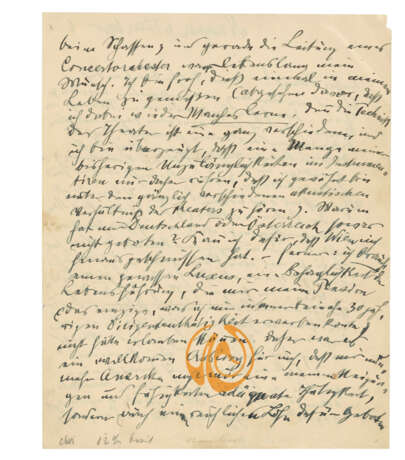

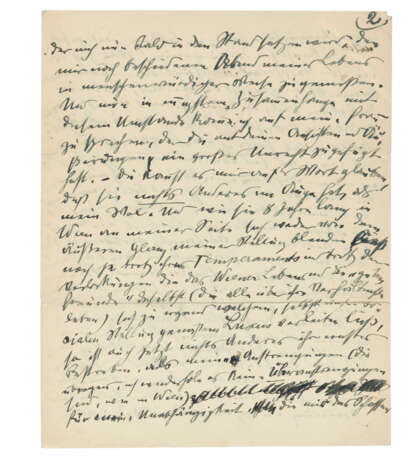

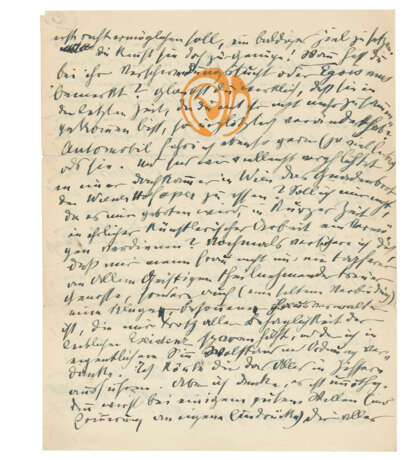

Autograph letter signed (‘Gustav Mahler’) to [Guido Adler: ‘Lieber Freund‘], New York, 1 January 1910

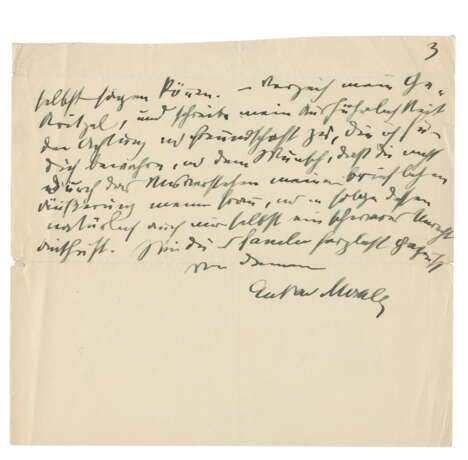

In German. 5 pages, 253 x 202mm and 185 x 202mm, the final page cut down from a full leaf, on Mahler's monogrammed stationery, scattered autograph cancellations, later pencil annotations. Provenance: Guido Adler (1855-1941) – ?Alma Mahler (1879-1964), apparently sent to her by Adler for inclusion in the Briefe; Sotheby’s, 16 May 1991, lot 311.

‘Can I help it that Vienna threw me out?’: Mahler robustly defends his wife Alma against any criticism and vociferously justifies his move to America in a final, long letter written to his friend and biographer Guido Adler. Adler has badly misunderstood Mahler’s situation, prompting an emphatic defence of his working practices in America (taking to his bed after rehearsals is a technique he learnt from Richard Strauss), his musical responsibilities (after all, ‘this very conducting of a concert orchestra was my lifelong wish’) and of the necessity of leaving Vienna: ‘America not only offered an occupation adequate to my inclinations and capabilities, but also an ample reward for it’. His most direct words are reserved for Adler’s opinion of his wife, whom Adler has done a great injustice. Insisting that Alma only has his welfare in mind, he defends her against any suggestion of extravagance or egotism, chastising Adler, who should know her better than that, and reminding him of the central role played by his wife in his life and career [full translation below].

Mahler’s relationship with his early biographer, the Viennese musicologist Guido Adler, has been the subject of some debate, largely thanks to the role played by Alma Mahler as editor of her husband’s letters and author of her own biographical remembrances. Mahler and Adler became friends as young men – not in childhood, as is sometimes stated – and supported one another’s musical careers as they developed in parallel; Mahler used the familiar ‘du’ to address Adler in his letters (see E. Reilly, ‘Mahler and Guido Adler’, The Musical Quarterly, vol. 58, no. 3, 1972, pp. 436–70). But Adler’s insistence that he belonged to Mahler’s most intimate circle of friends was somewhat undermined by one or two basic inaccuracies in his 1914 memorial essay on the composer, and, more notably, Alma Mahler's Gustav Mahler, Erinnerungen und Briefe makes few references to Adler, with those that she does include being largely unflattering. While Adler was among the ‘closest friends’ to whom Mahler first confided his engagement to Alma Schindler in a letter sent in December 1901 – and he is not thought to have been one of the group, lead by Siegfried Lipiner, who tried to disrupt the relationship of the newly-engaged couple by spreading rumours about Alma’s conduct – it seems that by the years immediately preceding Mahler’s death, she had come to group Adler with those older friends of her husband whom she admitted to disliking. Adler certainly believed that Alma was responsible for the decision to leave Vienna for America and that she had deliberately tried to separate her husband from his older friends, moving Alma to write to him in the summer of 1909 to try and allay his fears: ‘I have learned that you have the feeling that it might have been my intention to alienate you from Gustav!’. Some of Adler’s fears for Mahler seemed to him to have been founded when he received a letter from his friend, written from New York at the end of 1909, describing the ‘turmoil’ and strain of his life in America and he evidently replied with some concern, prompting the present letter from Mahler, an extraordinarily frank defence of Alma, his decision to move to America and his life there. When Alma asked Adler for his letters from Mahler for publication following the death of her husband, he responded by giving her only this letter: unlike the rest of Mahler’s correspondence, held with Adler’s papers at the University of Georgia Library (ms769), this letter is the only one that shows serious friction between Adler and Mahler, with Alma Mahler as the source.

Published: Gustav Mahler Briefe, ed. Alma Mahler (1924), no 416; full English translation published by Reilly (ibid.; see below).

'Dear Friend! My last letter seems to have been badly misunderstood by you. I learn this from a quantity of letters that I have been getting from Vienna for several days; and from them it is apparent that most unjust and (I admit it) also vexing interpretations have been linked to it. Thus firstly, ad vocem letter: I often go to bed after rehearsals (I first heard of this hygiene from Richard Strauss) because it rests me splendidly and agrees with me excellently. In Vienna I simply had no time for that. - I have very much to do, but by no means too much, as in Vienna. On the whole I feel myself fresher and healthier in this activity and mode of life than in many years. - Do you really believe that a man as accustomed to activity as I am could feel lastingly well as a "pensioner"? I absolutely require a practical exercise of my musical abilities as a counterpoise to the enormous inner happenings in creating; and this very conducting of a concert orchestra was my lifelong wish. I am happy to be able to enjoy this once in my life (not to mention that I am learning much in the process, for the technique of the theatre is an entirely different one, and I am convinced that a great many of my previous shortcomings in instrumentation are entirely due to the fact that I am accustomed to hearing under the entirely different acoustical conditions of the theater). Why has not Germany or Austria offered something similar? Can I help it that Vienna threw me out? - Further: I need a certain luxury, a comfort in the conduct of life, which my pension (the only one that I could earn in almost thirty years of directorial activity) could not have permitted. Thus it was a more welcome way out for me that America not only offered an occupation adequate to my inclinations and capabilities, but also an ample reward for it, which soon now will put me in a position to enjoy that evening of my life still allotted to me in a manner worthy of a human being. And now, most closely connected with this situation, I come to speak of my wife, whom you with your views and utterances have done a great injustice. You can take my word for it that she has nothing other than my welfare in view. And just as at my side in Vienna for eight years she neither allowed herself to be blinded by the outer glamour of my position, nor allowed herself to be seduced into any luxury even quite appropriate to our social position, in spite of her temperament and the temptations to do so from Viennese life and "good friends" there (who all live beyond their circumstances), so now also her earnest endeavour is nothing else than to put a quick end to my exertions (which, by the way, I repeat, are not overexertions, as in Vienna) for my independence, which should make it possible for me to create more than ever. You certainly know her well enough! When have you noticed extravagance or egotism in her? Do you really believe that in the time recently that you have no longer seen each other that she has changed so very suddenly? I like to drive a car as much as (indeed much more than) she. And are we perhaps obligated to eat the charity bread of the Vienna Court Opera in a garret in Vienna? Should I not, inasmuch as it is offered me, in a short time earn a fortune in honorable artistic work? Once more I assure you that to me my wife is not only a brave, faithful companion, sharing in everything intellectually, but also (a rare combination) a clever, prudent steward, who without regard for all the comfort of bodily existence helps me put by money, and to whom I owe well-being and order in the true sense. I could amplify all this with figures. But I think that is unnecessary; with some good will (and remembrance of past impressions), you will be able to say everything yourself. - Forgive my scrawl, and attribute my prolixity to the regard and friendship I preserve for you, and to the wish that you will not inflict a grievous injustice upon my wife, and hence on me also, through misunderstanding of an expression in my letter'. [translation]

| Artiste: | Gustav Mahler (1860 - 1911) |

|---|---|

| Lieu d'origine: | Autriche |

| Artiste: | Gustav Mahler (1860 - 1911) |

|---|---|

| Lieu d'origine: | Autriche |

| Adresse de l'enchère |

CHRISTIE'S 8 King Street, St. James's SW1Y 6QT London Royaume-Uni | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aperçu |

| |||||

| Téléphone | +44 (0)20 7839 9060 | |||||

| Commission | see on Website | |||||

| Conditions d'utilisation | Conditions d'utilisation |