ID 1249771

Lot 32 | Hugo Ripelin of Strasbourg (c.1210–1268), OP

Valeur estimée

£ 30 000 – 50 000

Compendium theologicae veritatis, with the prologues and additions of Raymond Gaultier (active 1411), OFM, and Jean Barthélémy (active 1446–67), OFM, in Latin, illuminated manuscript on vellum [France, Paris, c.1470]

A significant addition to the oeuvre of the Franciscan Jean Barthélémy: the only recorded text of his reworking of the one of the most widely read medieval manuals of practical theology, Hugo Ripelin of Strasbourg's Compendium.

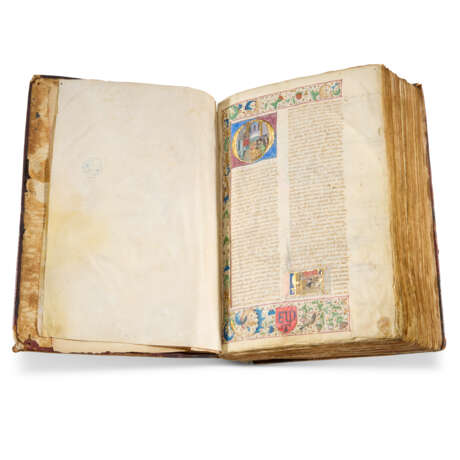

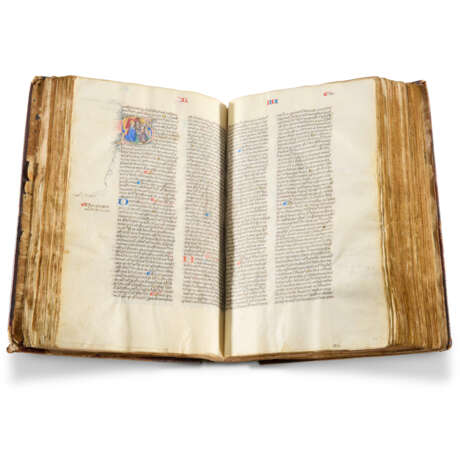

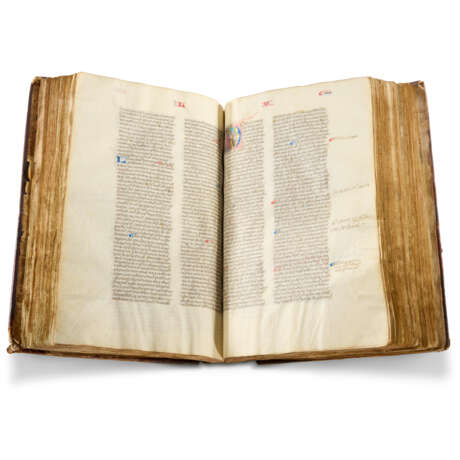

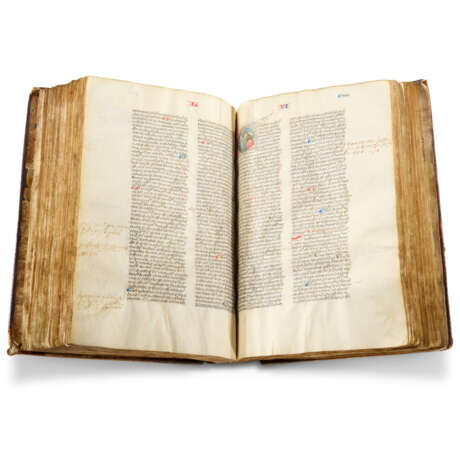

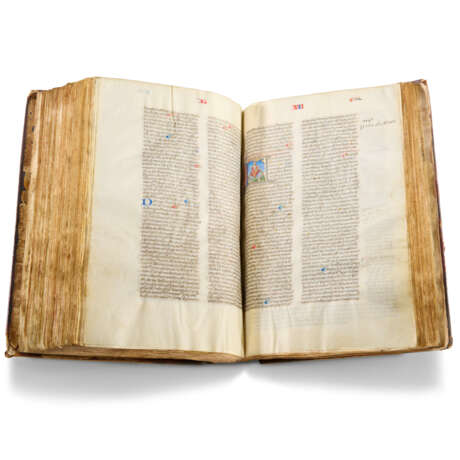

c. 290 × 110mm. i paper + ii + 342 + i + iii paper leaves: 16, 2–438, complete, catchwords in lower margins of final versos, signatures, original foliation beginning at 15 on f.15, 50 lines written in black ink in lettre batârde by two hands in two columns between four verticals and 51 horizontals, justification: 212 x 61-13-60mm, prickings for horizontals and verticals remaining on many leaves, glosses or additions by the second hand on many leaves, text capitals touched yellow, some rubrics underlined in red, paragraph marks in red or blue, running headings in red and blue, large initials in red or blue, eight historiated initials with staves of blue and burnished gold part fleur de lys flourished in red and black or blue, one large historiated initial with burnished gold staves on a ground of red and blue patterned with white with a border to three sides, of acanthus, flowers and birds between gold disks on hairline tendrils (ink faded and wear to smaller initial f.1, some slight losses of flesh paint in initials, staining to ff.207–208, wear to margins). Bound in 18th-century French red morocco, the covers and spine compartments with double gilt fillets (scuffed, stained, upper joint splitting). In a red cloth box.

Provenance:

(1) The manuscript can be localised to Paris: the apparatus of the Franciscan Jean Barthélémy was composed in Paris in 1467; the scribe Hugo Sellari did not add a year or place to his name – Scripto per me hugonem sellarii. 28. octobris deo gratias, f.139v – but presumably had access to Barthélémy's own copy and papers: by 1469 Barthélémy had died in Paris and the Franciscan Convent there had seized his books. The style of the miniatures also supports a Parisian origin. The commissioner was not apparently armigerous: instead of a conventional charge, the shield, integral to the border on f.1, bears the initials E and P either side of a Z-shaped bracket above a tau cross. This might relate to a merchant's mark and the tau cross to the Antonite Order, whose badge it was. To have chosen this redaction, however, the patron must have been in close contact with the Franciscans and some of the additions are intended for preachers. Since the Compendium is usually found in more directly functional, unillustrated copies, he was possibly an educated layman, commissioning a gift for a clerical library. Frequent annotations, many in a 17th-century hand, show that the book continued to be studied, perhaps within a religious house.

(2) Michel de Léon (1727–1800), trésorier de France en la généralité de Provence: with his armorial bookplate inside the front cover. His notable library was dispersed after his death; the fonds Michel Léon in the Bibliothèque municipale at Marseille consists of local material acquired in 1837.

(3) Blue book ink-stamp of two interlaced ‘C’s in an oval (ff.ii and iiiv).

(4) The Hispanic Society of America, New York (their B2589; this number on the box and in pencil on the front pastedown); sold at Christie’s, London, 12 November 2008, lot 32.

Content:

Prologue of Jean Bartélémy, f.1: ‘Opitulante altissimi gratia […] magistro Hugone Argentinensi sacri ordinis predicatorum … magister Raymundus Galteri ordinis minorum conventus Tholosam […] qui prefatum librum ampliavit […] magister Jo. Bartholomei ordinis minorum provincie Burgundie custodie Bisontinensis et conventus Chariaci […] Septemque librorum additamentis completis addidi ipse Bartholomei […] Completus est autem pro ultima sui additione Parisius anno domini 1467 …’.

Prologue of Raymond Gaultier, ff.1–2: ‘Fons rigans agrum totius ecclesie […] Et hec de prologo Raymundi Galteri et Hugonis Argentinensis dicta sufficiant’.

Hugo Ripelin of Strasbourg (de Argentina, Argentinensis), Compendium theologicae veritatis, as amplified by Raymond Gaultier and Jean Barthélémy, ff.2–293: Book I, on the Trinity, f.2, ‘Veritatis theologice sublimitas […]’; the scribe leaving blank lines after the heading for chapter 24 at the end of the first gathering, f.14v, and a second scribe continuing on f.15 with the text of chapter 24; Book II, on the Creation, ‘Summe bonitatis triplex est effluxio […]’, f.29v; Book III, on the corruption of sin, ‘Determinatis igitur breviter aliquibus de trinitate […]’, f.60v; Book IV, on the Incarnation, ‘Sicut deus rerum omnium est principium […]’, f.111v, ending with a scribal note ‘Et hec de quarto libro dicta sufficiant scripto per me Hugonem Sellarii, 28a Octobris deo gratias’, f.139v; Book V, on Grace, ‘Postquam dictum est de vita […]’, f.140; Book VI, on the Sacraments, ‘Celestis medicus humani generis […]’, f.196; Book VII, on the Four Last Things, ‘Finale judicium quedam sunt […]’, f.245, ending ‘[…] odium dei quod est summum peccatum. Explicit liber totus.’

Jean Barthélémy, Index for preaching following the liturgical year, according to Franciscan use, with references to the Bible and to the Compendium by book and chapter number: ‘In nomine patris et filii et spiritus sancti amen. Incipit adaptacio theumatum predicabilium [...] Si licet homini relinquet uxorem. Mat.19. Explicit’, ff.293–303.

Jean Barthélémy, Theological and liturgical dictionary, arranged alphabetically from Apostolus to Zachaeus, ‘Ista que sequntur non sunt de libro precedenti […]’, ff.303–340.

List of heretics, based on Rabanus Maurus, De clericorum institutione, II 24: ‘Quidam heretici qui de ecclesia recesserunt..., ff.340-341v; Condemnation of sinnners, Puniciones et comminaciones dei ad peccatores. Deut.11. si custodieritis […]’, ff.341v–342v, also found in other manuscripts e.g. Vatican, Vat. lat. 1346, a 12th-century canon law compilation.

Hortulus animae added by a later hand, f.342v.

The Compendium theologicae veritatis was one of the most widely read manuals of practical theology, giving an abstract theological context for practical advice on living a Christian life. At least 800 manuscripts survive, as well as fourteen incunable editions, and it was translated into French, German, Dutch, Italian and Armenian. This manuscript with its expanded text is listed by neither Kaeppeli, Scriptores ordinis praedicatorum medii aevi, 1970–1993, nor M. Bloomfield et al. Incipits of Latin works on the Virtues and Vices 1100–1500, 1979, pp. 550–53; for further manuscripts of German origin and for the text and its author, see G. Steer, Hugo Ripelin von Strassburg, zur Rezeptions- und Wirkungsgeschichte des ‘Compendium theologicae veritatis’ im deutschen Spätmittelalter, 1981.The influence of the Compendium was especially strong in Germany and the Empire but has been discerned across Europe: from the works of Dante to those of the English mystic Richard Rolle to the author of an Icelandic penitential manual. Raymond Gaultier’s knowledge of its author's name, Hugh of Strasbourg, was not widespread and Hugo’s name did not appear in the printed editions. Hugo Ripelin, therefore, fell into obscurity as his enormously popular work was attributed to his Dominican contemporary, St Albertus Magnus, and the younger Dominicans St Thomas Aquinas and Ulrich of Strasbourg, as well as to the Franciscan, St Bonaventura, whose Breviloquium, completed by 1254, served as a model for the Compendium. Modern editions of the Compendium are included in the complete works of Albertus Magnus (ed. Borgnet, 1893) and of Bonaventura (ed. Peltier, 1866).

Hugo Ripelin, one of the first German Dominicans, joined the Order in his home town of Strasbourg; from 1232 to 1259 he served as prior in the Zürich convent, founded from Strasbourg in 1229, and then returned to Strasbourg where he died in 1268. Traditionally regarded as a pupil of Albertus Magnus, he was actually Albertus’s contemporary and his contribution to the thought of Albertus and Aquinas is now being re-assessed, as well as the extent to which his work was used by others, often without acknowledgement. There seems to have been a revived interest in the Compendium in the 15th century, with a sudden increase in the number of manuscripts matched by the demand for printed editions. In 1481, shortly after the production of the present manuscript, an illustrated copy of the French translation was written for the noted bibliophiles Antoine de Chourses and Catherine de Coëtivy at Hesdin (Chantilly, Musée Condé, ms 130, see C. Michler, Le somme abregiet de theologie, die altfränzösische Übersetzung des ‘Compendium theologicae veritatis’ Hugo Ripelins von Strassburg, 1996). The present lot is a magnificent example of that renewed interest, with its two stages of amplification offering new insight into how this hugely influential work was used and understood in 15th-century France.

Raymond Gaultier of the Toulouse Franciscans, who used the Compendium as the core for a collection of further authorities on key issues of Christian belief and practice, was presumably the Frater Ramundus Galterii who in 1411 bought for the use of himself and other brothers of the Toulouse Convent a copy of the Theologicum doctrinale of Alain du Puy, a biblical dictionary that may well have assisted his work on the Compendium (Avignon, Bibliothèque municipale, ms 332). What may be a copy of Raymond's original work, before the further additions of Jean Barthélémy, is in the Bibliothèque municipale of Avignon, ms 332, with a colophon of 1460. It has the same prologue but the seven books are differently arranged, with incipits that do not always agree with either Hugo's original or those of the present lot; the adaptor, evidently Franciscan, is not apparently named.

Further study should elucidate the relationship between the three texts and whether part of Barthélémy's work was to bring Gaultier's version closer to its source. Certainly the present lot, after Gaultier's and Barthélémy's intervention, is considerably enlarged from Hugo's original, with Book III, for instance, having 111 chapters instead of 33. The dramatic expansion of this book, dealing with sin, is typical of the practical emphasis of the text’s adaptors. Jean Bartélémy has been known only as an author of vernacular devotional works, so that the present lot is a significant addition to his oeuvre and one containing further biographical information: that he was from the Franciscan convent of Chariacum, Chariez, in the custody of Besançon in the Franche Comté (for his career, see Dictionnaire de spiritualité, I, col. 1270). First documented at Soissons in 1446, he was preaching in Rouen shortly before coming to study at the university of Paris in 1451. Sent on preaching missions to Nantes, Nevers, and Tours, he was based in Paris where he was spiritual counsellor to the Poor Clares of Longchamp, for whom he wrote treatises in French (see Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal ms 2123; BnF, ms. fr 9611). His library was extensive, as might be deduced from the authorities he used for his work on the Compendium, cited on f.1, and was the subject of a lawsuit after his death between the now Observant house at Chariez, the Franciscan province of Burgundy and the Franciscan Convent in Paris; Paris and Chariez were to share the books pending a decision by the Pope (L. Beaumont Maillet, Le grand couvent des Cordeliers à Paris, 1975, p.198). This is apparently the only recorded text of his reworking of the Compendium.

Illumination:

The exquisite historiated initials were provided by the Master of Jean Rolin II, named from his miniatures in missals painted for the Bishop of Autun, of which one in Lyon is still intact (Bibliothèque municipale, ms 517). Working here on a small scale, he produced scenes of exceptional refinement, particularly evident in the minute touches of liquid gold used to model draperies. The Master was based in Paris where he collaborated with the Bedford Workshop and inherited their patterns and traditions (see F. Avril and N. Reynaud, Les manuscrits à peintures en France 1440–1520, 1993, pp. 38–45). His activity is usually considered to have ended around 1465, a date that needs to be extended from the evidence of the present manuscript, a copy of works composed in 1467. It is one of the few datable manuscripts in his oeuvre; another is the Hours of Simon de Varie (divided between the Royal Library in The Hague and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles) with the date of 1455 in the text, where his work appears alongside that of the Dunois Master and Jean Fouquet. The Master was given the challenge of historiating a text that was rarely illustrated: even the Chources-Coëtivy copy has only one miniature, of the Trinity. He encapsulated the theme of Book III on sin with a devil tapping the shoulder of a man holding a money bag: sin may result in worldly gain but eternal loss and damnation. Book V, on grace, opens with Christ giving a drink to a kneeling woman, perhaps a personification of the soul. Other scenes – Creation, Annunciation, Baptism of Christ, and Last Judgement – could be adapted from standard patterns, while the first three initials of preaching, by a talented assistant, relate to similar scenes in one of the Master's most splendid works, the Horloge de sapience of Henry Suso, the 14th-century Rhineland mystic profoundly influenced by the Compendium (Brussels, KBR, ms IV 111). In two initials, however, the Dominicans of the Horloge de sapience have become Franciscans to reflect, not the original author of the Compendium, but its expanders and, possibly, its intended readers.

The subjects of the historiated initials are as follows:

f.1 Franciscan preaching in a church to a lay audience; Dominican lecturing a clerical audience

f.2 Franciscan lecturing a clerical audience

f.39v Christ as Creator of the world

f.60v Devil accosting a man in a landscape

f.111v The Annunciation

| Lieu d'origine: | Europe de l'Ouest, France, Europe |

|---|---|

| Catégorie maison de vente aux enchères: | Manuscrits médiévaux et de la Renaissance, Livres et manuscrits |

| Lieu d'origine: | Europe de l'Ouest, France, Europe |

|---|---|

| Catégorie maison de vente aux enchères: | Manuscrits médiévaux et de la Renaissance, Livres et manuscrits |

| Adresse de l'enchère |

CHRISTIE'S 8 King Street, St. James's SW1Y 6QT London Royaume-Uni | |

|---|---|---|

| Aperçu |

| |

| Téléphone | +44 (0)20 7839 9060 | |

| Commission | see on Website | |

| Conditions d'utilisation | Conditions d'utilisation |