Jean Béguin (1550-1620); Andreas Libavius (c.1550-1616); Jacques Besson (c.1530-1572)

09.07.2025 10:30UTC +00:00

Classic

Prix de départ

5000GBP £ 5 000

| Auctioneer | CHRISTIE'S |

|---|---|

| Lieu de l'événement | Royaume-Uni, London |

| Commission | see on Website% |

Archive

La vente aux enchères est terminée. Vous ne pouvez plus enchérir.

ID 1450457

Lot 27 | Jean Béguin (1550-1620); Andreas Libavius (c.1550-1616); Jacques Besson (c.1530-1572)

Valeur estimée

£ 5 000 – 8 000

Alchimiae Praxis, in Latin, illustrated manuscript on paper, Paris, 1663

An illustrated manuscript of early practical chemistry, written at a time when the study of alchemy was transmuting into the new genre of scientific chemical literature.

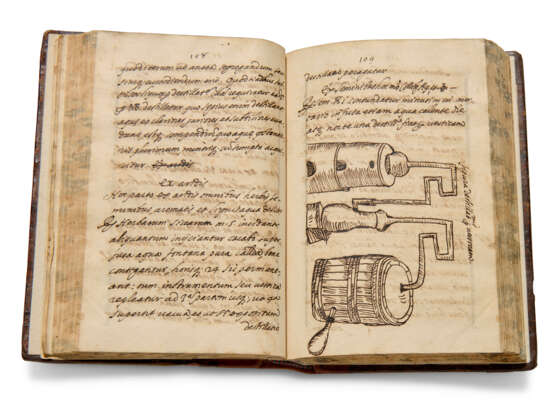

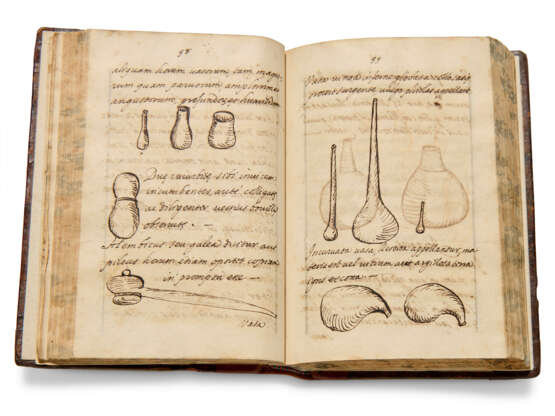

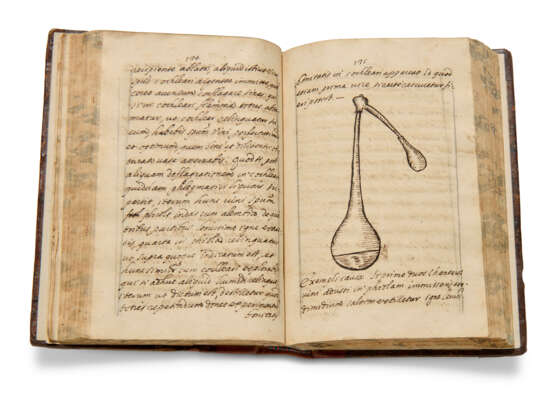

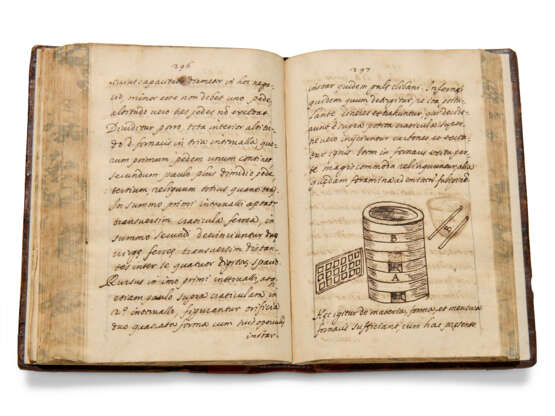

158 x 112mm. 218 leaves, complete, collation: 1-178, 1810, 19-278, contemporary pagination 1-404 followed here, c.17 lines, written space: c.125 x 80mm, a smaller illustrated bifolium tipped in at front, 32 ink drawings of alchemical equipment and processes (some marginal thumbing and staining and ink show-through). Bound in contemporary mottled calf tooled in gold (rebacked, a little scuffed).

Provenance:

(1) The paragraph at the foot of the title-page dates and localises the manuscript to Paris, 1663, and claims the authors are unknown, suggesting one may be Parisian and another Belgian: ‘Autores huius libelli ignoti sunt. Primus Parisiensis quidam. Secundus Belga fuisse creditur. Scripti cum Rubricula inferius copiose ad Parisiis anno 1663’. The authors are, in fact, Jean Béguin (of Lorraine – perhaps the ‘Belga’?), the German Andreas Libavius, of Halle, and Jacques Besson (born in Colombières – then part of Dauphiny, now part of Italy).

(2) By the 18th-century the manuscript must have been in Italian ownership: notes regarding Romulus and Bonaventura are scribbled in Italian on f.218v.

Content: Alchimiae Praxis pp.1-404: Jean Béguin (1550-1620), Tyrocinium chymicum, based on the unauthorised 1610 printing, beginning with the excerpt from pseudo-Paracelsus ‘Discende primum Digestiones’ followed by ‘Alchymia est ars que purum ab impuro separare docet’, pp.1-95; Andreas Libavius (c.1550-1616), ‘Chymistarum Tractatus’, beginning ‘In arte destillatoria, imo in quavis separatione’, pp.96-292; Jacques Besson (c.1530-1572), Tractatus de Absoluta ratione extrahendi olea, et Aquas e medicamentis simplicibus, beginning ‘Rosmarinus, Sperpillum, Ruta’, pp.293-336 ; Andreas Libavius (c.1550-1616), ‘De apparatu mineralium ad usum medicum’, beginning ‘Sublimatio nihil aliud est’, pp.337-404; index (unpaginated) ff.203-218.

The manuscript is a compilation of some of the earliest and most important texts on practical chemistry as distinct but still fundamentally linked to alchemy. Jean Béguin, apothecary, chemist and aumônier du roi under Henri IV founded one of the very first schools of chemistry in Paris. His Tyrocinium chymicum is generally recognised as setting the preconditions for the emergence of the whole genre of scientific chemical literature later in the century. It proved extremely popular, going through several editions and translations throughout the 17th century. The text here does not identify Béguin as the author, and the opening differs from the first official 1612 Paris edition of the Tyrocinium: it follows rather the pirated edition from 1611 by Anton Botzer of Cologne based on lectures printed by Béguin for his students in 1610 (also copying the opening epigram to the reader ‘Quisquis es o lector […]’). Notably – and emblematic of how fluid definitions of alchemy and chemistry were at the time – the 1611 unauthorised edition begins ‘Alchymia est ars […]’, while the official 1612 edition omits the ‘Al’ and opens ‘Chymia est ars […]’ (on this see W. R. Newman and L.M. Principe, ‘Alchemy vs. Chemistry: The Etymological Origins of a Historiographic Mistake’, Early Science and Medicine, Vol. 3, no 1 (1998), pp.49-5).

The second work is Andreas Libavius’ Praxis Alchymiae, first printed at Frankfurt in 1604, here titled ‘Chymistarum Tractatus’. Libavius was a polymath: he wrote dozens of works on topics ranging from logic to theology, poetry to chemistry, medicine, physics and pharmacy. In 1597 he wrote the first systematic chemistry textbook, Alchymia, where he described the possibility of transmutation. Our manuscript follows the 1604 edition very closely: the many ink-drawings present are almost identical to their printed counterpart.

As in the 1604 edition of Libavius’ Praxis Alchymiae, the text that follows is Jacque Besson’s Tractatus de Absoluta ratione extrahendi olea, et Aquas e medicamentis simplicibus, which first appeared in Zurich in 1554 appended to Conrad Gesner’s De secretis remediis liber. Besson was a mathematician and engineer and this work focuses specifically on the process of distillation, especially the method by which medicinal distillates can be extracted from a variety of plants. Following Besson’s work in this manuscript is the second part of the Libavius’ Praxis Alchymie, ‘De Mineralium Apparatu’.

| Lieu d'origine: | Europe de l'Ouest, France, Europe |

|---|---|

| Catégorie maison de vente aux enchères: | Manuscrits médiévaux et de la Renaissance, Médecine et sciences, Livres et manuscrits |

| Lieu d'origine: | Europe de l'Ouest, France, Europe |

|---|---|

| Catégorie maison de vente aux enchères: | Manuscrits médiévaux et de la Renaissance, Médecine et sciences, Livres et manuscrits |

| Adresse de l'enchère |

CHRISTIE'S 8 King Street, St. James's SW1Y 6QT London Royaume-Uni | |

|---|---|---|

| Aperçu |

| |

| Téléphone | +44 (0)20 7839 9060 | |

| Commission | see on Website | |

| Conditions d'utilisation | Conditions d'utilisation |