QIANLONG, Emperor of China (1711-1799) – Giuseppe CASTIGLIONE (1688-1766, artist) and Charles-Nicolas COCHIN (1715-1790, engraver)

06.07.2023 12:00UTC +00:00

Classic

Vendu

239400GBP £ 239 400

| Auctioneer | CHRISTIE'S |

|---|---|

| Lieu de l'événement | Royaume-Uni, London |

| Commission | see on Website% |

Archive

La vente aux enchères est terminée. Vous ne pouvez plus enchérir.

ID 992785

Lot 38 | QIANLONG, Emperor of China (1711-1799) – Giuseppe CASTIGLIONE (1688-1766, artist) and Charles-Nicolas COCHIN (1715-1790, engraver)

Valeur estimée

£ 120 000 – 180 000

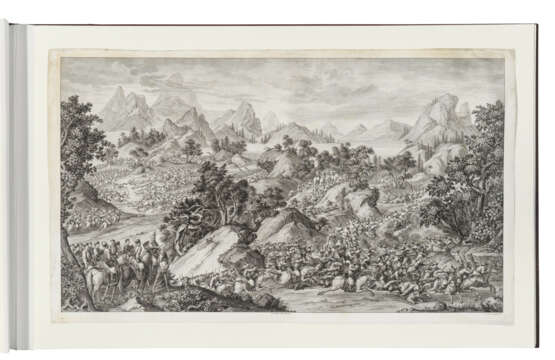

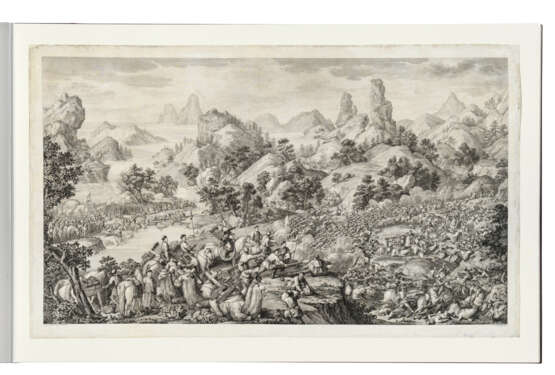

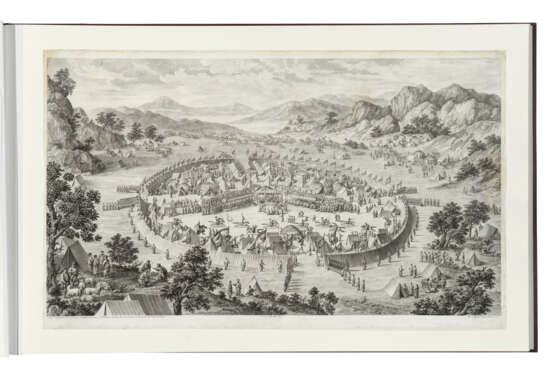

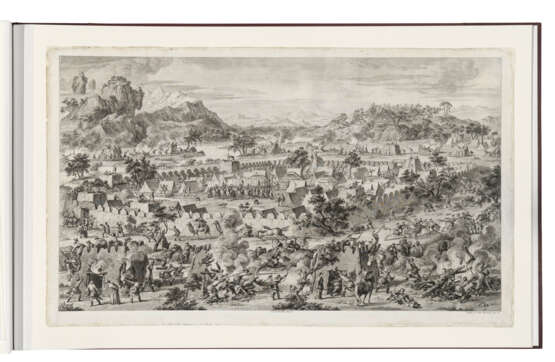

[Pingding Xiyu zhantu. Suite de seize estampes representant les conquetes de l'Empereur de la Chine. Paris: 1767-1774.]

Extremely rare, complete suite of 16 large copper engravings, commemorating Emperor's Qianlong's victorious campaigns in Central Asia between 1755-1759.

First French edition, 16 copper-engraved plates (each with plate mark approx. 550 x 930mm on sheets approx. 557 x 940mm), mounted on sheets within album.

JESUIT ARTISTS AT THE QIANLONG IMPERIAL COURT

In the late 17th century, a number of European Jesuit painters served in the Qing court of the Kangxi Emperor, who was interested in employing European Jesuits trained in various fields, including painting. In the early 18th century, Jesuits in China made a request for a painter to be sent to the imperial court in Beijing. Giuseppe Castiglione, a Jesuit lay brother of Milanese descent, was identified as a promising candidate and he accepted the post.

In August 1715, Castiglione arrived in Macau, China, and reached Beijing later in the year. He stayed at a Jesuit church called St Joseph Mission or Eastern Hall (Dong Tang) in Chinese. He was presented to the Kangxi Emperor, and was initially assigned to work as an artisan in the palace enamelling workshop. While in China, Castiglione took the name Lang Shining (郞世寧), and adapted his European painting style to Chinese themes and taste. Castiglione’s skill as an artist was appreciated by the Qianlong Emperor, serving the emperor for three decades and was granted increasingly higher official rank within the Qing court. He spent many years in the court painting various subjects, including the portraits of the emperor and empress, as well as the tribute horses presented to the Emperor.

The Qianlong Emperor, like his predecessors, took his cultural role seriously. A promoter of the Manchu heritage, he ordered the compilation of Manchu language genealogies, histories, and ritual handbooks. He was also an extremely prolific poet and essayist, with his collected writings containing more than 40,000 poems and 1,300 prose texts. The Emperor's massive art collection became an intimate part of his life, taking landscape paintings with him on his travels to compare them with the actual landscapes, and because of the Jesuits at court, he had contact with western art.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Born Aisin-Gioro Hongli, the fourth son of the Yongzheng Emperor and Noble Consort Xi, Hongli was made a qinwang (first-rank prince) under the title ‘Prince Bao of the First Rank’. The Emperor did not designate any of his sons as the crown prince, but Hongli seems to have enjoyed a ‘favourite’ status, being assigned tours of inspection to the south, and appointed chief regent on occasions when his father was away from the capital. He became known as a capable negotiator and enforcer, and these attributes probably enabled him to win the battle of succession against his elder half-brother Hongshi.

Upon his accession in 1735, Hongli adopted the era name ‘Qianlong,’ meaning ‘Lasting Eminence,’ and sent armies to suppress the Miao rebellion (1735-1736) in south-west China. This military success set the template for what the emperor would later call The Ten Great Campaigns (Shiquan Wugong). This series of military actions included three to enlarge the area of Qing control in Inner Asia: two against the Dzungars (or Zunghars, 1755-1758), and the ‘pacification’ of Xinjiang (1758-1759), and this present lot was commissioned by the emperor to commemorate these events. The other seven campaigns were two wars to suppress the Gyalrong of Jinchuan, Sichuan, another to suppress the Taiwanese Aboriginals (1787-1788), and four expeditions abroad against the Burmese (1765-1769), the Vietnamese (1788-1789), and two campaigns against the Gurkhas on the border between Tibet and Nepal (1790-1792).

The present lot is a pictorial record of the campaign against the Dzungars, while the following two lots record the Taiwanese and Nepalese actions.

THREE CAMPAIGNS AGAINST THE DZUNGARS AND THE PACIFICATION OF XINJIANG (1755-1759)

From the end of the 17th century, the Dzungar Khanate fought against the Qing dynasty and its Mongol vassals in a series of conflicts. Of the Ten Campaigns, the Qianlong Emperor’s victory over the Dzungars was the most significant as it brought these wars to their conclusion, secured the northern and western boundaries of Xinjiang, and eliminated rivalry for control over the Dalai Lama in Tibet as well as any other rival influence in Mongolia.

In 1752, the Dzungar aristocrat Dawachi (d.1759) and the Khoit-Oirat prince Amursana (1723-1757) competed for the title of Khan of the Dzungars. After several defeats, Amursana fled with his small army and sought protection of the Qianlong Emperor. In return for Amursana recognizing Qing authority, the Qianlong Emperor supported Amursana and sent the Manchu General Zhaohui to lead a campaign against the Dzungars. After several skirmishes and small scale battles along the Ili River, the Qing army, led by Zhaohui, approached Ili (modern-day Yining or Ghulja) and forced Dawachi to surrender. Qianlong appointed Amursana as the Khan of Khoid and one of four equal khans – much to the displeasure of Amursana, who wanted to be the Khan of the Dzungars.

Feeling betrayed and his authority undermined, Amursana, with the help of Prince Chingünjav, now rallied the majority of the remaining Oirats to rebel against Qing authority. The Qianlong Emperor again deployed General Zhaohui, this time to suppress Amursana. The Dzungar leader Ayushi defected to the Qing side and attacked the Dzungar camp at Gadan-Ola (Battle of Gadan-Ola).In 1757, General Zhaohui defeated the Dzungars at the Battle of Oroi-Jalatu, attacking Amursana's camp at night. Despite the element of surprise, Amursana was able to fight on until Zhaohui received enough reinforcements to drive him away. Subsequently, the Chinese under Prince Cabdan-jab defeated Amursana at the Battle of Khorgos, before Zhaohui finally defeated Amursana at Mount Khurungui. This was a particularly daring attack, as it involved a river crossing and a night-time assault. Defeated, Amursana fled to Russia.

After this second campaign against the Dzungars, two Altishahr nobles, the Khoja brothers Burhan al-Din and Khwaja-i Jahan, brought together the remaining Dzungars, Kyrgyz peoples and the Oases Turkic peoples (Uyghurs) in Altishahr (the Tarim Basin) and started a revolt against the Qing dynasty. Zhaohui once again went on the offensive, and by the end of 1758, there were only two fortresses left in rebel hands, Yarkand and Kashgar. Zhaohui unsuccessfully besieged Yarkand and fought an indecisive battle outside the city (the Battle of Tonguzluq). Zhaohui instead took other towns east of Yarkand but was forced to retreat; the Dzungar and Uyghur rebels laid siege to him at the siege of Black River (Kara Usu). In 1759, Zhaohui asked for reinforcements and 600 troops were sent. On 3 February 1759, over 5,000 enemy cavalry led by Burhan al-Din ambushed the 600 relief troops at the Battle of Qurman. Despite superior numbers, the Uyghur and Dzungar cavalry charge was halted by artillery, musketry and archers, and the Qing troops forced the Dzungars to withdraw. This led to the military collapse of the rebels, with the Dzungar cavalry defeated at the Battle of Qos-Qulaq, and the subsequent retreat and defeat of the Uyghurs at the Battle of Arcul (Altishahr) on 1 September 1759. With a further defeat at the Battle of Yesil Kol Nor, Burhan al-Din and Khwaja-i Jahan fled with their small army of supporters to Badakhshan. There, the Sultan Shah attacked them, handed over the captured rebels to Qing forces, and submitted to the Qing dynasty.

On 13 July 1765, Qianlong, inspired by prints of battles by the Augsburg engraver Georg Philipp Rugendas the Elder (1666-1742), commissioned wall paintings celebrating his victories over the Dzungars for the central hall of the Palace in Beijing. These were to be undertaken by four Jesuits: Giuseppe Castiglione, the director of the project, Jean-Denis Attiret, Ignatius Sichelbarth and Jean Damascene.

Louis-Joseph Le Febvre, head of the French Jesuit mission to China, appears to have suggested that engravings should be made of these paintings, and consequently reduced drawings were sent to Paris, where the engravings were executed by eight artists under the direction of Charles-Nicolas Cochin of the Academie Royale at the Court of Louis XVI.

This commission was considered of utmost importance, as it potentially offered France means of leaving a favorable impression on the Emperor and thus gaining advantage in view of commerce and missioning, directed against the Dutch, Portuguese and English. The Qianlong Emperor requested an edition of one hundred copies only; however, to ensure the safe receipt of at least one hundred copies in China, an edition of 200 copies was actually printed. To reduce the risk of loss at sea, they were distributed over two ships in lots of 100 impressions each. The entire edition was received in China by 1775 for which the Compagnie Francaise des Indes in Canton was paid the sum of 240,000 pounds. Only a very limited number of extra copies was printed for the French King, his ministers and some members of the Court, and the greatest precaution was taken that no copies remained with the engravers or printers to ensure its exclusivity.

Literature

W. Fuchs, ‘Die Entwürfe der Schlachtenkupfer in der Kienlung- und Taokuangzeit‘ in Monumenta Serica, 4 (1939-40), 101-122

W. Fuchs, ‘Der Kupferdruck in China vom 10. Bis 19. Jahrhundert‘ in Gutenberg Jahrbuch (1950) pp. 67-87

Paul Pelliot, ‘Les "Conquêtes de l’Empereur de la Chine"’, in Toung Pao, 20 (1921), pp. 183-274; and also Toung Pao, 25 (1928), pp. 132-133; and Toung Pao, 29 (1932), pp.125-127

M. Pirazzoli-T’Serstevens, Gravures des Conquêtes de l’Empereur de Chine K’ien-long au Musée Guimet (Paris, 1969)

S.L. Shaw, The imperial printing of early Chʾing China, 1644-1805 (San Francisco 1984)

Tanya Szrajber, ‘The “Victories” of the emperor Qianlong’ in Print Quarterly, 23.1 (2006) pp.28-47

Takata Tokio, ‘Qianlong Emperor’s Copperplate Engravings of the “Conquest of Western Regions,”’ in The Memoirs of the Tokyo Bunko, 70 (2012)

Joanna Waley-Cohen, ‘Commemorating War in Eighteenth-Century China’ in Modern Asian Studies 30.4 (1996) pp.869-899

Special notice

No VAT is payable on the hammer price or the buyer's premium for this lot. Please see the VAT Symbols and Explanation section of the Conditions of Sale for further information

| Lieu d'origine: | Chine, Asie de l'Est, Europe de l'Ouest, France, Asie, Europe |

|---|---|

| Catégorie: | Impressions d'art |

| Lieu d'origine: | Chine, Asie de l'Est, Europe de l'Ouest, France, Asie, Europe |

|---|---|

| Catégorie: | Impressions d'art |

| Adresse de l'enchère |

CHRISTIE'S 8 King Street, St. James's SW1Y 6QT London Royaume-Uni | |

|---|---|---|

| Aperçu |

| |

| Téléphone | +44 (0)20 7839 9060 | |

| Commission | see on Website | |

| Conditions d'utilisation | Conditions d'utilisation |