ID 1108899

Lot 100 | Robert Graves (1895-1985)

Valeur estimée

£ 20 000 – 30 000

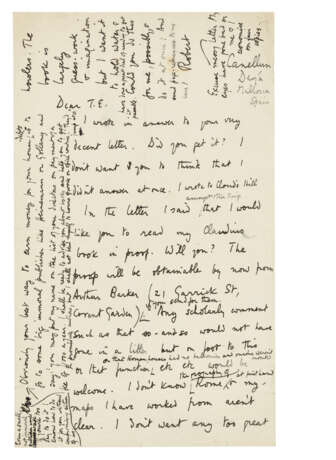

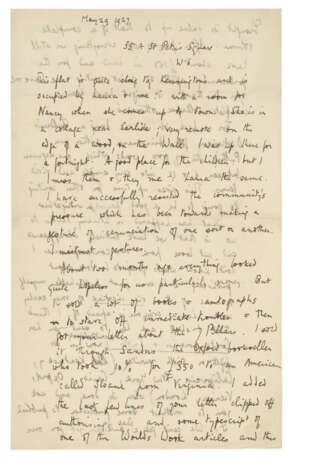

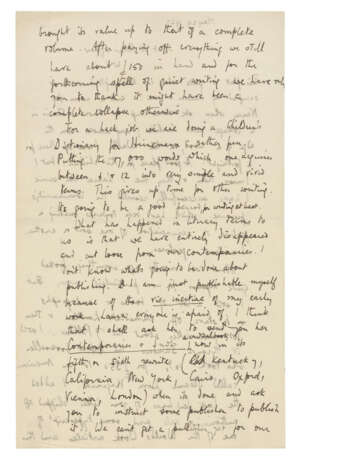

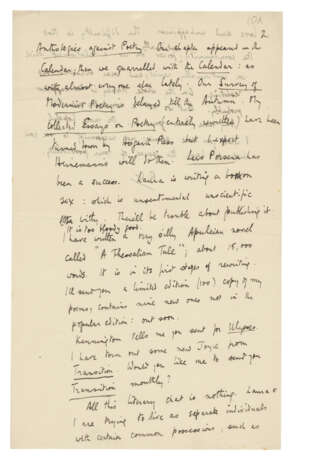

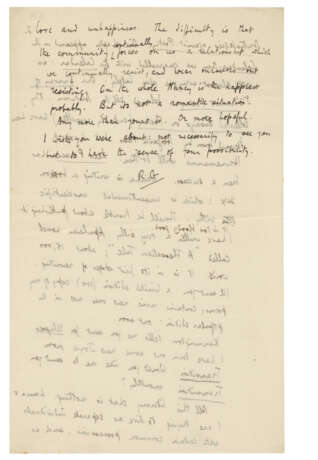

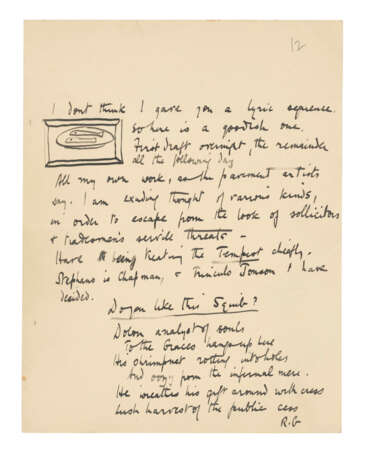

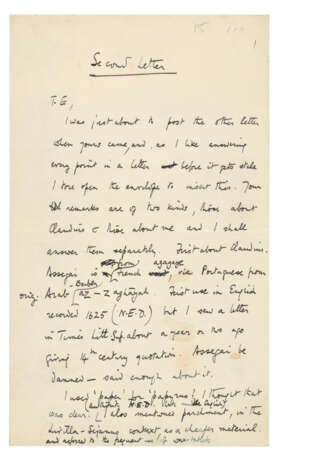

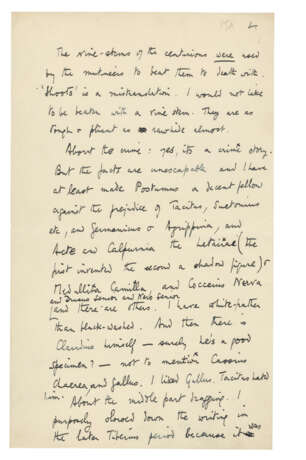

35 autograph letters signed (‘Robert’, ‘R.G’, or ‘Robert Graves’) to T.E. Lawrence (‘T.E.’, ‘Lawrence’ or ‘T.E.L.’), Mallorca, Oxford, London, Rottingdean and elsewhere, generally n.d. [c.1922-1933]

Along with one typed letter signed and annotated in autograph, one postcard and a telegram. c.97 pages in total, various sizes (130 x 75mm to 327 x 200mm), one with a pencil note by Lawrence on verso, another annotated by Laura Riding. Provenance: Sotheby's, 20 & 21 July 1981, lot 253.

An important series of letters, chiefly unpublished, to T.E. Lawrence from his biographer Robert Graves, encompassing Graves’ literary career and his relationship with Laura Riding across the formative years of the twenties and early thirties.

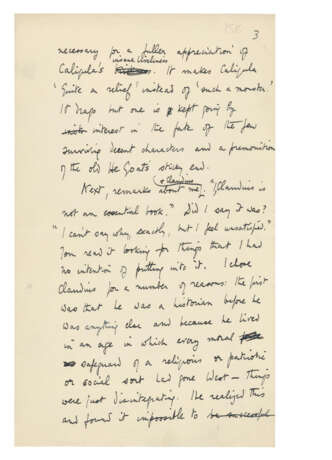

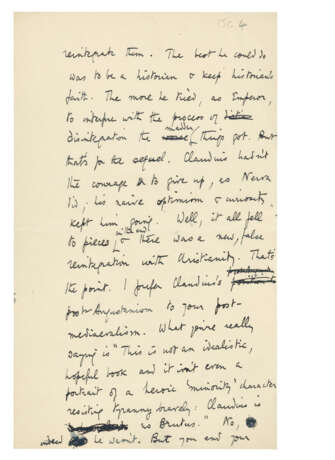

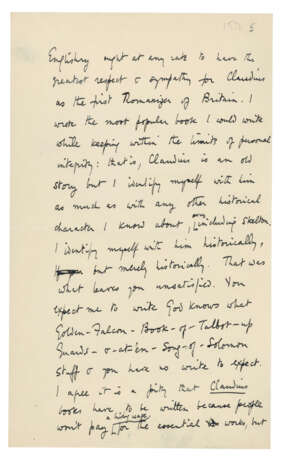

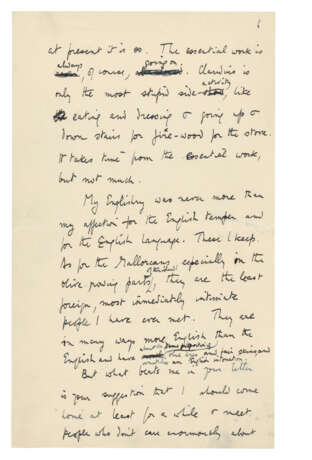

Literature dominates the present correspondence, particularly Graves’ own work: from putative projects in both prose and poetry to his most famous work, I, Claudius, which Lawrence read in proof (after Graves requests ‘Any scholarly comment such as that so-and-so would not have gone in a litter but on foot to this or that function or that Roman houses had no balconies and onions weren’t invented’) and offered his critique, to which Graves responded in great detail (‘"I, Claudius is not an essential book." Did I say it was? […] You read it looking for things that I had no intention of putting into it. I chose Claudius for a number of reasons: the first was that he was a historian before he was anything else and because he lived in an age in which every moral safeguard of a religious or patriotic or social sort had gone West – things were just disintegrating. The best he could do was to be a historian and keep historian's faith. The more he tried, as Emperor, to interfere with the process of disintegration the madder things got. But that's for the sequel [...] I wrote the most popular book I could write while keeping within the limits of personal integrity: that is, Claudius is an old story but I identify myself with him as much as with any other historical character I know about’). Certain of the projects mentioned by Graves – and sometimes sent to Lawrence in draft form, ‘because you like watching things grow’ – were apparently destined to remain unpublished, while elsewhere we see the genesis of works such as The Real David Copperfield (1933) – ‘rewriting David Copperfield as Dickens would have written it of he had not broken down half-way at the Little Emily trouble and ratted on his characters’ – and Claudius the God (1935), with particular focus on the biography of Herod Agrippa. The range of projects on which Graves is occupied is notably broad – the correspondence opens with discussion of his short-lived quarterly The Owl, Graves asking Lawrence if he should ask Eric Kennington to contribute his illustrations – but he does not neglect to commend the work of fellow writers, as well as congratulating his friend on Seven Pillars of Wisdom (1926) (‘Cortez and Pizarro had an awfully easy job compared with your Arabian problem; they started as a legend and only had to swash a few buckles and there they were. But to start as a suspect member of a despised culture as you did, that's a different show’), suggesting that Lawrence is in danger of having written a classic. Siegfried Sassoon is mentioned only in brief, with Graves expressing his ambivalence.

Laura Riding is never far from Graves’ thoughts: he reports often on her writing, especially that on which they have been working together (with Laura revising some of his own works – ‘It was awful’, she notes of one in a post-script); describes their life in Deià, with their private press sometimes laying idle for longer than they would like; and in a rare dated letter, written from Hammersmith on 29 March 1927, offers Lawrence his understanding of their situation within the literary establishment: ‘What has happened in literary terms to us is that we have entirely disappeared and cut loose from our contemporaries […] I am just publishable myself because of the vis inertiae of my early work. Laura everyone is afraid of’. The professional and the personal are, inevitably, inextricably intertwined here: in the earlier correspondence, Graves makes frequent reference to the difficulties engendered by the unorthodox arrangement of his relationship with Laura and his wife Nancy (‘I have successfully resisted the community’s pressure which has been towards making a gesture of renunciation of one sort or another’), with sympathy for Nancy – whose breakdowns and desire to live without him are mentioned here, sometimes almost in passing – finally giving way to despair at the point of his break from his wife in 1929, when Laura threw herself from a fourth-floor window (‘If you can come to us on Whitsun I’ll tell you the whole story which is grotesque from an ordinary point of view’). The situation between Lawrence and Riding was scarcely easier at times, with Graves moved to write in one letter: ‘I have felt very unhappy about the breach between you and Laura and would give a great deal to have it healed […] I can only say that it is a great loss to me that Laura who is my best friend & you to whom I have always felt more closely than any other man should be not ever on terms of greeting distantly’. In the same letter, Graves offers Lawrence financial support – ‘I could find the money in March when I begin to cash in on Claudius’ – and adds a note of concern:‘ I am sorry you have to leave the R.A.F. because you suited it & it you; but it has probably done its job of slowing you down – I only hope not too well. I am hoping for a recovery of mental speed in you’. Later in the correspondence, the tables are turned and Graves has evidently asked Lawrence for assistance with money following the construction of his house in Mallorca: after one such appeal, Lawrence sent him a presentation copy of Seven Pillars, which Graves reports having sold for £350 through an Oxford bookseller to an American.

Robert Graves and T.E. Lawrence met and became friends at Oxford; Graves wrote the first major biography of T.E. Lawrence: Lawrence and the Arabs, published in 1927. In a letter of 24 January 1933, Lawrence wrote to his friend: ‘R.G. has been a main current influencing my life, for nearly 15 years […] any line from you matters more than screeds from others’. Only six of the present 35 letters are published – sometimes only partially – in Letters to T. E. Lawrence.

| Artiste: | Thomas Edward Lawrence (1888 - 1935) |

|---|---|

| Lieu d'origine: | Angleterre, Espagne |

| Artiste: | Thomas Edward Lawrence (1888 - 1935) |

|---|---|

| Lieu d'origine: | Angleterre, Espagne |

| Adresse de l'enchère |

CHRISTIE'S 8 King Street, St. James's SW1Y 6QT London Royaume-Uni | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aperçu |

| |||||

| Téléphone | +44 (0)20 7839 9060 | |||||

| Commission | see on Website | |||||

| Conditions d'utilisation | Conditions d'utilisation |