ID 1279159

Lot 18 | SPACESUIT COVER-LAYER MADE FOR ASTRONAUT EDWARD WHITE

Valeur estimée

$ 80 000 – 120 000

DAVID CLARK CO., INC. IN JANUARY 1964

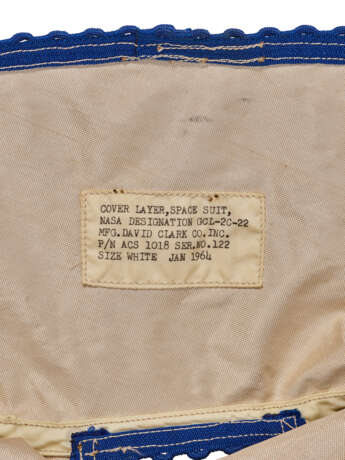

Aluminized nylon pressure suit cover-layer, with original affixed NASA “meatball” patch and exterior name tag reading “E.H. White, II,” the hose and zipper attachment openings with blue rickrack trim. The interior label reads “Cover Layer, Space Suit, / NASA Designation GCL-2C-22 / Mfg. David Clark Co. Inc. / P/N ACS 1018 Ser. No. 122 / Size White Jan 1964”.

Ed White’s spacesuit cover-layer from the first phase of the Gemini Program: an iconic survival from the first spacesuit series designed specifically to sustain human life in outer space (Young, p. 47).

Edward White II (1930-1967) was an Air Force test pilot with an aeronautical engineering background when he was selected as one of the “Next Nine,” i.e. just the second batch of NASA astronauts after the Mercury Seven. The mission of the Gemini Program, announced in January 1962, included two important steps in the goal of landing men on the Moon: to accomplish rendezvous and docking between two spacecraft in orbit; and to prove that astronauts could survive in space for the necessary duration, both inside and outside the spacecraft. A newly designed spacesuit was of course essential to these goals.

For most of the Mercury Program, the spacesuit contractor was B.F. Goodrich and they designed two new separate pressure-suit systems in 1962/1963. As development continued, however, Goodrich’s design was rejected in favor of the one produced by David Clark Co. of Worcester, Massachusetts—although the Clark suit still used a Goodrich helmet, gloves and boots. Both the Goodrich and Clark versions used the same silver-colored aluminum-coated nylon fabric that was made iconic by the Mercury Seven. In June of 1963, Clark Company was awarded the contract and their suit went into production. The tag inside this suit indicates it was the 22nd one Clark Co. made, and was released in January, 1964. “[The contract] called for the design and construction of a suit able to function in some very specific mission-oriented situations. This was the first time that the spacesuit was considered the prime system required to sustain life. Redundancies had to be built in to make certain of this, while still ensuring that while pressurized, the astronaut would have an adequate degree of mobility with low levels of fatigue. Additionally, the suits were required to have an acceptable level of micro-meteoroid protection, astronaut visibility, and maintenance of body temperature in the extreme heat of cold and space” (Young, p.47).

Ed White can be seen wearing a spacesuit cover-layer identical to this one in his official NASA portrait taken on 10 September 1964. The full pressure suit had two layers, this outer layer and an inner “restraint” layer made of rubber and Neoprene. White would have continued to wear this spacesuit during his training, based out of NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, now the Johnson Space Center. By repute, the present lot was purchased circa 1991 from the estate sale of Ken Sharp, a Houston auto mechanic who befriended both the Mercury and Gemini astronauts through his work on their Corvettes. The astronauts were all presented with Corvettes as part of a GM publicity stunt and their mechanic was able to form a significant collection of these early artefacts.

After a few months of training and development testing, this silvery coated cover-layer would be supplanted by a new version, made of an off-white high-temperature resistant nylon which was later branded Nomex. It was in a Nomex-covered suit that Ed White became the first American to walk in space, on 3 June 1965 during Gemini-Titan 4. White spent over 20 minutes outside of the spacecraft and famously had to be ordered back inside because he was enjoying himself so thoroughly. On his return to Earth, his historic spacewalk was honored with a NASA Exceptional Service Medal and a promotion to the rank of lieutenant colonel.

In March 1966, White was selected for the first crewed Apollo flight, along with fellow Gemini-alum Gus Grissom and new astronaut, Roger Chaffee. Tragically, all three men perished in training for Apollo 1. During a launch simulation conducted about a month before the planned mission, an unstoppable fire broke out in the highly-pressurized, 100% oxygen environment of the command module. After the tragedy, many new safety measures were introduced. One of these was to replace Nomex with a fire-retardant fabric. All the manned Apollo mission spacesuits after Apollo 1 used Teflon-coated Beta cloth. See Amanda Young, Spacesuits: The Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum Collection, 2009, chapters 3 and 5, and fig. 3.4. Overall this suit is in excellent condition. The areas of rusting to the aluminum coating are typical of this fabric and less prominent compared to Deke Slayton’s version of the same spacesuit held at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (inventory no. A19730854000).

66 in. (167.6 cm.)

Provenance

Edward White II (1930-1967).

Ken Sharp, Houston.

Private Collection.

Acquired by the late owner, 2002.

| Catégorie maison de vente aux enchères: | Tous les autres types d'objets |

|---|

| Catégorie maison de vente aux enchères: | Tous les autres types d'objets |

|---|

| Adresse de l'enchère |

CHRISTIE'S 8 King Street, St. James's SW1Y 6QT London Royaume-Uni | |

|---|---|---|

| Aperçu |

| |

| Téléphone | +44 (0)20 7839 9060 | |

| Commission | see on Website | |

| Conditions d'utilisation | Conditions d'utilisation |