ID 1214851

Lot 62 | The Lindesiana Chronicles of Scotland

Valeur estimée

£ 150 000 – 250 000

The ‘Schøyen chronicle’ and John Major’s Historia Maioris Brittanniae, in Latin, manuscript on paper [Scotland, probably Edinburgh, c.1511 and c.1526]

A remarkable discovery for Scottish history: the ‘Schøyen chronicle’. A unique contemporary addition to the historical narrative for the first War of Scottish Independence and the sole surviving source for new details of William Wallace’s 1297 uprising. In a rare early Scottish binding – one of only a handful of pre-1550 Scottish decorated bookbindings to survive – and with extensive 16th-century Scottish provenance, including John Lindsay of Balcarres (1552-1598), Scottish Secretary of State.

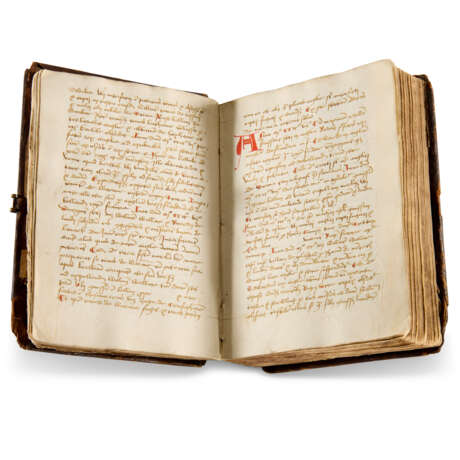

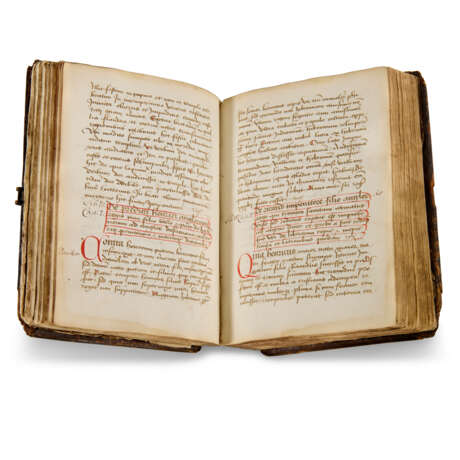

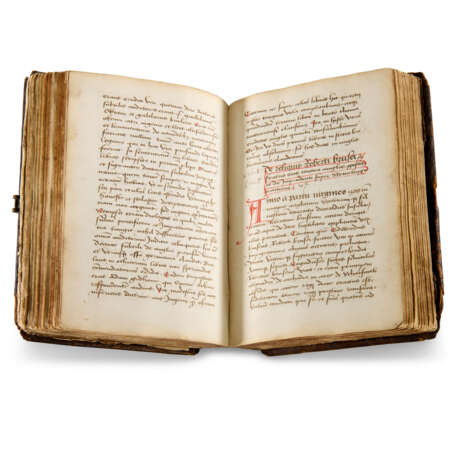

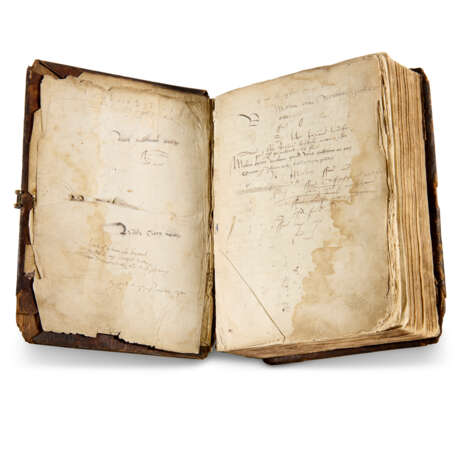

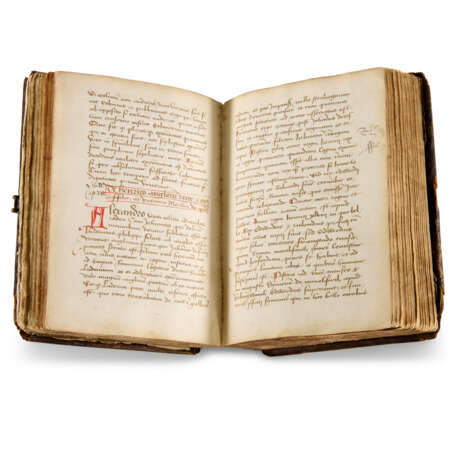

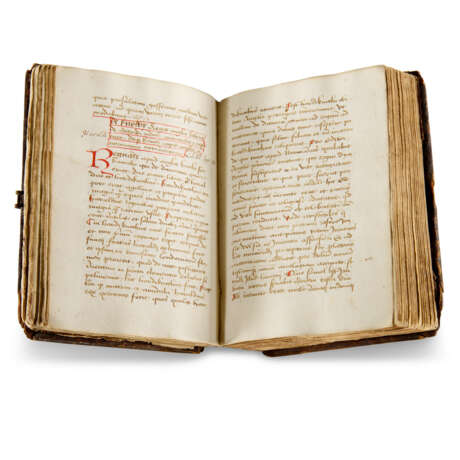

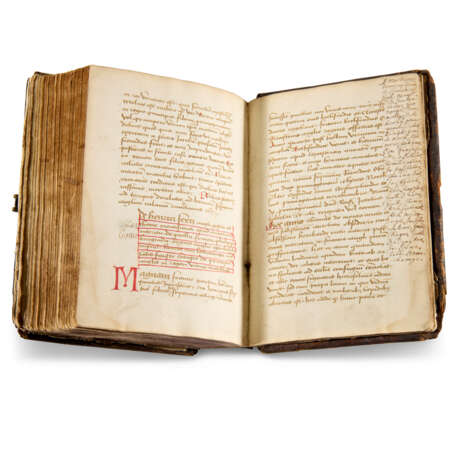

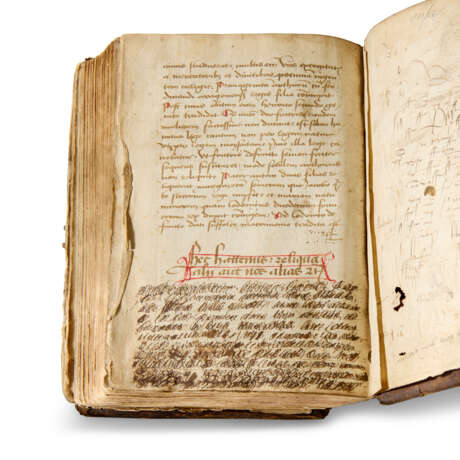

195 x 138mm. i + 223 leaves + i, apparently complete, collation: 116, 216, 37 (of 8, vii cancelled), 4-88, 97 (of 8, vii cancelled), 10-268, 271 (of 2, ii a cancelled blank), written in two campaigns by two different scribes, 26-27 lines per page, written space: c.153 x 98mm, rubrics underlined in red, capitals touched in red, three-line decorative initials in red throughout, contemporary and later marginal annotations scattered throughout in Latin and English (front flyleaf loose, some tattering and waterstaining to the leading page edges of the first gathering, lower binding stitches of the first gathering loose).

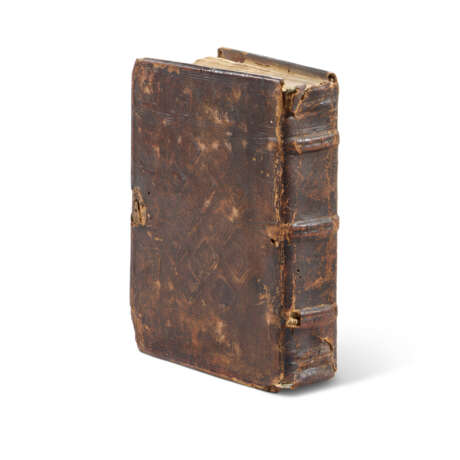

Binding:

Contemporary Scottish blindstamped calf over inner-bevelled wooden boards, sides framed and diapered with quadruple fillets and tooled with 2 stamps, one square of a ?grazing animal, the other a small rectangle of two animals, probably a dog chasing a hare, 3 raised double-bands on spine outlined with blind fillets, remains of a single clasp (lightly worn with only minor loss); modern box.

Provenance:

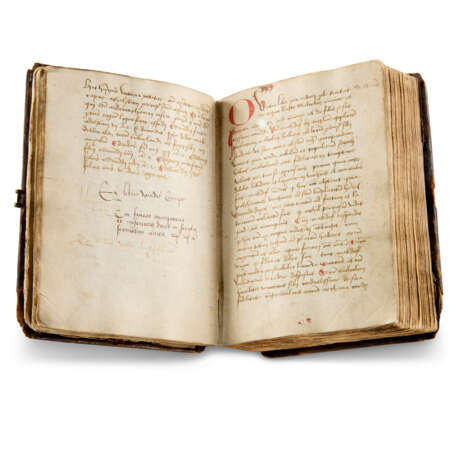

(1) Robert Robertoun, chaplain of Edinburgh (?d. c.1568): his ownership inscription on the front flyleaf (‘Liber D[o]m[ini] Roberti Robertoun Sacellani Edynburgi’) describing the book as a ‘Chronica Scotorum’. Perhaps the same Sir Robert Robertoun whose death appears among the records of the Trinity Church and Hospital, Edinburgh, after the town council granted in the name of the hospital a benefice left vacant by his decease on 15 October 1568 (J. Marwick. The history of the Collegiate Church and Hospital of the Holy Trinity and the Trinity Hospital, Edinburgh, 1460-1661, 1911, p.70). It was presumably at Robertoun’s behest that the two texts of the Lindesiana Chronicles of Scotland were bought together in a rare example of a medieval Scottish decorated binding.

(2) Members of the Kemp family: 16th-century ownership inscriptions of Henry (‘Liber hendericus kemp’; front flyleaf), George (‘Liber G[e]orgi Kemp’; front flyleaf), and David Kempe (‘Ex libris davidis kempe’; f.32).

(3) Walter Buchanan: his 16th-century ownership inscription on f.32v (‘Ex libris valteri buchquhanan’).

(4) John Lindsay of Balcarres, Lord Menmuir (1552-1598, Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal and Secretary of State, Scotland): his ownership inscription (‘liber Johannis Lindesay’) and motto (‘Malim eternum verbum quod uno auditur ab ore/ Quam si plena mihi biblioteca fovet’) on f.1r. Listed in A History and Catalogue of the Lindsay Library 1570-1792, eds. Williams, Stevenson & Zachs, no 639.

(5) H. Greer, bookseller, Bangor, Northern Ireland.

(6) Sotheby’s, 19 June 1990, lot 97.

(7) The Schøyen Collection, MS 679.

Content:

Manuscript I [c.1511]: Early legendary British history, apparently derived from Geoffrey of Monmouth and Henry Huntingdon (opening ‘Usque ad presens misit […]’) ff.1v-4v; account of Scottish origins, attributed to a Vita of St Brendan and to a Vita of St Congal, and a list of early Scottish (Dál Riata) and Pictish kings ff.4v-7v; account of English royalty from Edmund Ironside, Scottish royalty from Máel Coluim and St Margaret of Scotland, and the descendants of David, earl of Huntingdon (d. 1219) ff.7v-17v; account of Scottish events from 1285-1327 ff.17v-24; annals covering events in Scotland 1066-1390, apparently derived from Fordun or Bower ff.25-29; account of English rulers to King Edgar (d.975) ff.30-32v; extracts from Book V of Fordun’s Chronica, covering Scottish history 1058-1128 ff.33-38v.

Manuscript II [c.1526, copied in a different hand]: John Major, Historia Maioris Brittanniae, opening at Book II, chapter 4 (‘Vidimus quomodo a britonibus […]’), ff.38v-223, following the text first published in 1521. A later hand has marked both manuscripts – erroneously, in the first instance on f.33 – into books II-VI of Major’s History.

The principal sources for events in Scotland between the 13th and 14th centuries – the critical period leading up to and spanning the First War of Scottish Independence – are the chronicle texts surviving in manuscripts from the mid-15th century and later. The first major attempt at a continuous Scottish history was written in the mid-1380s by the priest John de Fordun, incorporating details from earlier chronicle-texts, primarily the Gesta Annalia, alongside material gathered during his travels in England and Ireland. Fordun’s Chronica Gentis Scotorum, in turn, formed the basis of the much larger Scottish history compiled by Walter Bower, Augustinian abbot of Inchcolm, in the 1440s and given the title Scotichronicon. Both Fordun and Bower began with a factual account of how a people from Ireland called the Scots came by the 11th century to dominate the whole of the area known today as Scotland; Bower had his scribe copy out all of Fordun’s earlier work, with his own revisions, whilst adding a great deal of material drawn from other sources, much of it designed to reinforce the idea of a separate Scottish national existence, free from the ambitions of the English kings to submit the Scots to English rule. Bower’s Scotichronicon also added more to the historical narrative after the mid-12th century, as Fordun’s work became more sparsely detailed, incorporating lost sources of chronicle-type through the 13th and 14th centuries and ending with a contemporary history of his own period down to 1437.

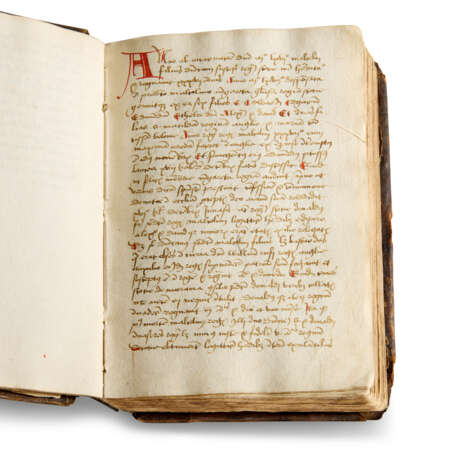

Across decades of copying, re-copying and textual transmission between the principle chronicles, crucial ‘new’ details appear in the historical narrative in certain manuscript sources – these sources contain material that is not derived from Fordun, Bower or, indeed, the Gesta Annalia and thus represent an entirely new discovery for Scottish history. The first manuscript of the Lindesiana Chronicles of Scotland constitutes one such discovery: the hitherto-unknown text on ff.18-24, named the ‘Schøyen chronicle’ by Dauvit Broun, is remarkable for containing details of events in Scotland during the first War of Independence that appear nowhere else (Broun, 2011). Our chronicle – which internal dating suggests was copied c.1511 – must represent the sole surviving copy of an earlier manuscript source, probably 14th century but now lost to us: while much of the text is derived from the Gesta Annalia or Scotichronicon, it is more accurate than both in places, which indicates that the 16th-century scribe was copying from a manuscript of a contemporary source. The Schøyen chronicle gives the name of the Earl of Buchan appointed guardian of the realm in 1286 correctly as Alexander – not John, as Gesta Annalia and Bower have it – and records the correct date for the capture of Simon Fraser (following the Battle of Methven) in 1306 on the feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary (15 August), where Bower gives it as the Annunciation (25 March). It also offers a specific date for the consecration of John Lindsay as Bishop of Glasgow – 9 October 1323 – where other texts record only that this elevation occurred before a written instruction issued by Pope John XXII on 10 October that Lindsay should return to Glasgow. We know our manuscript to have been copied from an earlier exemplar as certain names are left blank or are mistakenly transcribed by the scribe, suggesting some difficulty in reading the text he was reproducing, but these instances of greater history accuracy underline its credibility.

The most remarkable new details, those relating to the first War of Scottish Independence, are found on f.19 of the Schøyen chronicle – they shed crucial new light on the first act of rebellion against Edward I definitively known to have been carried out by William Wallace, the killing of the English sheriff of Lanark, William Heselrig. The assassination – an act of great symbolic importance, which swelled the ranks of Wallace’s original band of 30 men with many new followers – was hitherto recorded in the sources only as occurring in May 1297. With the discovery of the Schøyen chronicle we are furnished for the first time with an exact date: 3 May, the Feast of the Finding of the Holy Cross. Furthermore, recorded alongside this date is another entirely new piece of information. The full sentence reads: ‘Anno Domini mo ccic o vii o Surgunt Scoti videlicet Willelmus Wallace et Ricardus de Lundy subsidium eis congregates et interfecerunt vicecomitem de Lanark die Inuentionis Sancte Crucis [3 May]’ (‘In the year of Our Lord 1297, the Scots rose up, namely William Wallace and Richard of Lundie, who had gathered together a band of men, and they killed the sheriff of Lanark on the day of the Finding of the Holy Cross)’. No other source records anyone other than William Wallace as leader of the Scottish rebellion: our manuscript introduces for the first time Lundie as co-author of the 1297 uprising.

Sir Richard of Lundie has subsequently been mostly forgotten by the Scottish histories, likely because he deserted the Scots cause shortly after May 1297, when murmurs began to circulate that the leaders of the rebellion, including the future King Robert the Bruce, James Stewart and the Bishop of Glasgow, were negotiating a surrender: with the blood of the sheriff of Lanark on his hands, Broun suggests that Lundie might even have hoped for a pardon. After joining the English side, Lundie fought against William Wallace at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in September 1297 – he is recorded as making a canny suggestion to outflank the Scots at a nearby ford, which was overruled by the Earl of Surrey to the ultimate detriment of the English cause – though it is intriguing to note that the poet Blind Harry’s famous 15th-century account of the battle has Lundie on the side of the Scots (‘Wallace and Ramsay, Lundie, Boyd, and Graham/With dreadful strokes made them retire – Fy, shame!’). Either way, as the myth of William Wallace as the most durable and heroic of Scottish patriots grew, it would have been easier to erase the participation of a traitor to the Scots cause such as Richard of Lundie in the event that sparked the rebellion and have Wallace stand alone.

Elsewhere, the Schøyen chronicle offers fresh perspective on established events. For example, before the discovery of our manuscript, the only contemporary explanation for the murder of Duncan III, Earl of Fife, in 1289 was to be found in the Lanercost Chronicle covering the Wars of Scottish Independence, in which he is described as ‘cruel and greedy beyond the average’. Our manuscript presents things in a different light, as a dispute over property between two noblemen: we are told that Duncan was slain because he had ‘stolen the patrimony’ of the major landholder, a kinsman of the earl who sent the assassins. While the Schøyen chronicle is clearly not an entirely original text – assimilating as it does material from Fordun, Bower and other sources – it is of significant importance as a unique addition to the pool of chronicle material on the first War of Scottish Independence, a fresh witness offering new detail and comment.

Christie's is grateful for the assistance of Professor Dauvit Broun in the preparation of this catalogue note.

Literature

Broun, D., ‘New information on the Guardians’ appointment in 1286 and on Wallace’s rising in 1297’ and ‘A recently discovered Latin chronicle of the Wars of Independence’, Breaking of Britain: Cross-Border Society and Scottish Independence 1216-1314, 2011, online.

| Lieu d'origine: | Europe du Nord, Écosse, Europe, Royaume-Uni |

|---|---|

| Catégorie maison de vente aux enchères: | Manuscrits médiévaux et de la Renaissance, Livres et manuscrits |

| Lieu d'origine: | Europe du Nord, Écosse, Europe, Royaume-Uni |

|---|---|

| Catégorie maison de vente aux enchères: | Manuscrits médiévaux et de la Renaissance, Livres et manuscrits |

| Adresse de l'enchère |

CHRISTIE'S 8 King Street, St. James's SW1Y 6QT London Royaume-Uni | |

|---|---|---|

| Aperçu |

| |

| Téléphone | +44 (0)20 7839 9060 | |

| Commission | see on Website | |

| Conditions d'utilisation | Conditions d'utilisation |