American Silver - From Colonial Times to the Present

American silver holds a special place in the antique market. The country boasts long-standing traditions in working with precious metals, shaped by artisans free from the constraints of the Old World. In American silver, artistic creativity merged with innovative techniques arising from industrial development. Today, the works of renowned U.S. jewelers adorn the exhibits of the world's finest museums.

The History of American Colonial Silver

American silver was imported into Europe starting from the 16th century, with suppliers from Spanish colonies located in Peru and Mexico. There was no jewelry production in South America at the time; precious metal was coined into currency and sent to Spain. The first workshops emerged in the northern part of the continent, where settlers from Britain, bringing skills in working with precious metals, established themselves.

American Silver. Paul Revere. Sugar basket, 1796

American Silver. Paul Revere. Sugar basket, 1796

Early American silver differed from its European counterpart with bold designs and a variety of techniques. Colonies lacked the restrictions imposed by guilds on those authorized to craft and sell precious items. This allowed talented apprentices, blacksmiths, and even dentists to become jewelers. Any master proficient in metalworking techniques could pursue their craft, and many of them juggled multiple professions simultaneously.

American Silver. Paul Revere. Tea vessel, 1791

American Silver. Paul Revere. Tea vessel, 1791

Jewelers faced challenges due to a lack of raw materials, as they lacked access to South American deposits. Silversmiths melted down worn coins and outdated tableware, experimenting with alloy purity since there were no strict requirements for the alloy's cleanliness in the colonies. Adding other metals to silver was a common practice, providing a solution without affecting the appearance of the items.

American Silver. John Copley. Portrait of Paul Revere, 1768

American Silver. John Copley. Portrait of Paul Revere, 1768

One of the pioneers of American silversmithing was the engraver and industrialist Paul Revere. He crafted items with unconventional shapes and original designs, establishing the first mass production of tableware and accessories in the U.S. at his Boston factory. After the Civil War, a consumer boom ensued, leading to high demand for silver. Revere introduced rolling machines at his factory, significantly reducing production costs and making the products accessible to the middle class. Neoclassicism was highly popular during this period, evident in the tea sets of the time.

American Silver. Paul Revere. A factory-made teapot made of silver leaf, 1796

American Silver. Paul Revere. A factory-made teapot made of silver leaf, 1796

Silver in the United States from the Republic to the Present Day

After the declaration of independence in the United States, the government took measures to regulate the jewelry industry. In 1792, the mint established a silver standard, requiring a minimum of 89.2% precious metal content in the alloy. The highest grade of 92.5% was consistent with British legislation. Stringent government regulation posed some challenges for workshops, but with the discovery of the Comstock Lode in Nevada in 1858, the issue of raw material scarcity was ultimately resolved.

American Silver. Thomas Fletcher and Sydney Gardiner. A silver urn, 1830

American Silver. Thomas Fletcher and Sydney Gardiner. A silver urn, 1830

By 1830, the popular European Rococo style had replaced the simple and elegant Neoclassical style. The design of items became more intricate, with floral motifs dominating the finish, executed in the repoussé technique. Founded in 1837, the Tiffany & Co. soon became a trendsetter in the jewelry industry. The company pioneered mail-order distribution of goods through catalogs and sold products from renowned workshops in its stores, including Grosjean & Woodward, William Gale, and Gorham Mfg Co. Items were marked with double hallmarks — those of the craftsman and the selling firm.

American Silver. William Gale and Son. Silver jug, sold through the Tiffany and Co shop, 1862-1867

American Silver. William Gale and Son. Silver jug, sold through the Tiffany and Co shop, 1862-1867

At the turn of the 20th century, decorative art in the United States was entirely influenced by Art Nouveau from Europe. Smooth patterns and botanical motifs adorned nearly all items — from vases to revolver handles. Masters showcased their best creations at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. The central piece of the exhibition was a vase from Tiffany & Co. with ceramic and gold detailing, recognized as an outstanding masterpiece of Art Nouveau jewelry art.

American Silver. Tiffany and Co. Magnolia vase, silver, gold, ceramic, opals, circa 1893

American Silver. Tiffany and Co. Magnolia vase, silver, gold, ceramic, opals, circa 1893

Art Deco became the dominant style of Gorham's factory, known for its Martele line featuring unusual curved shapes and decoration with waves, plant ornamentation, and female figures. Silversmiths worked by hand and used soft silver with minimal impurities. The factory practiced division of labor: blacksmiths shaped the required form of the item, while engravers applied the patterns. It took about 140 hours to produce one vase or coffee pot.

American Silver. Gorham Manufacturing Company. Pitcher on Martele stand, 1901

American Silver. Gorham Manufacturing Company. Pitcher on Martele stand, 1901

Artistic experiments continued until the 1930s, and outstanding Art Deco masterpieces today adorn the exhibits of many museums. Simultaneously, American industry mass-produced avant-garde items sold in regular department stores. The tea set collection of Paul A. Lobel gained popularity among art enthusiasts and became an exhibit at the 1934 Metropolitan Museum, but it did not sell well among buyers due to the financial strain caused by the Great Depression.

American Silver. Paul A. Lobel. Tea or coffee service, 1934

American Silver. Paul A. Lobel. Tea or coffee service, 1934

In the mid-20th century, silverware manufacturers faced serious competition from stainless steel tableware producers. However, many companies continued to work with silver until the early 1980s. One of the renowned manufacturers, the International Silver Company, whose works were repeatedly recognized as icons of modern design. Today, Tiffany & Co holds a leading position in the market — the sterling silver of the manufacturer is in demand worldwide.

Alberto Giacometti was a great sculptor of the 20th century who relentlessly shattered the stereotypes of art in search of creative self-expression

Alberto Giacometti was a great sculptor of the 20th century who relentlessly shattered the stereotypes of art in search of creative self-expression  Performance art - provocative art with profound meaning

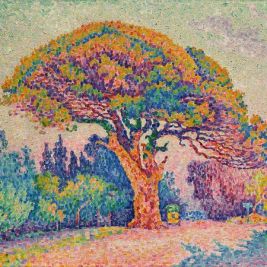

Performance art - provocative art with profound meaning  Post-Impressionism is a joyful and unconventional style in painting

Post-Impressionism is a joyful and unconventional style in painting  Order of Carlos III is the highest civilian award in Spain

Order of Carlos III is the highest civilian award in Spain  Vanitas is a genre of art that prompts the viewer to contemplate the inevitability of death

Vanitas is a genre of art that prompts the viewer to contemplate the inevitability of death  Auction: essence, types, history, the most famous art auctions

Auction: essence, types, history, the most famous art auctions  The top 10 most famous Spanish artists - the greatest masters of art of all time

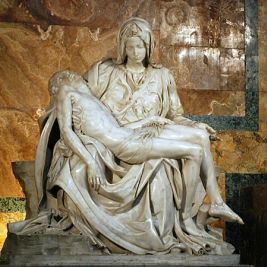

The top 10 most famous Spanish artists - the greatest masters of art of all time  Sculpture "The Pietà" by Michelangelo Buonarroti is a iconic work in Catholicism

Sculpture "The Pietà" by Michelangelo Buonarroti is a iconic work in Catholicism  The Resurgence of Vintage Kitchen and Barware: A Collector’s Delight

The Resurgence of Vintage Kitchen and Barware: A Collector’s Delight  Armand was a brilliant French artist who timely abandoned his career as a painter to later become a globally renowned sculptor

Armand was a brilliant French artist who timely abandoned his career as a painter to later become a globally renowned sculptor