ID 1024644

Lot 108 | Albert Einstein (1879-1955).

Valeur estimée

CNY 7 000 000 – 10 000 000

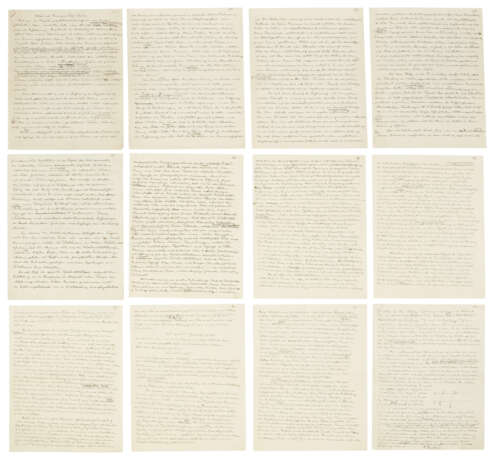

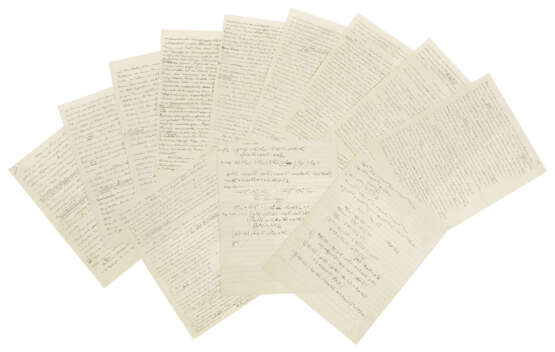

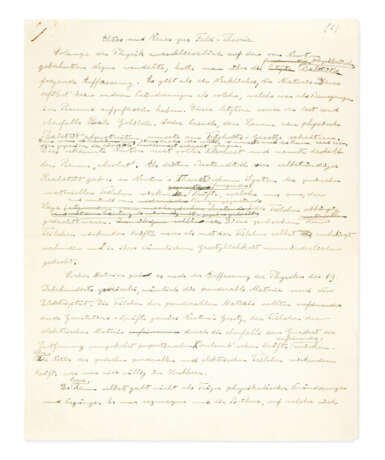

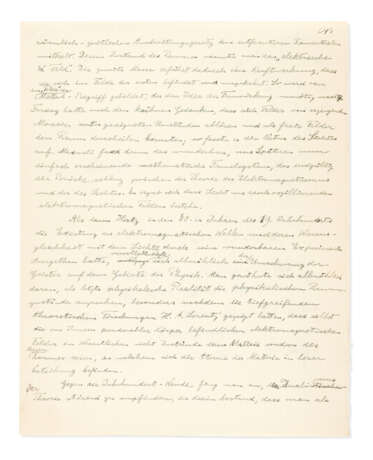

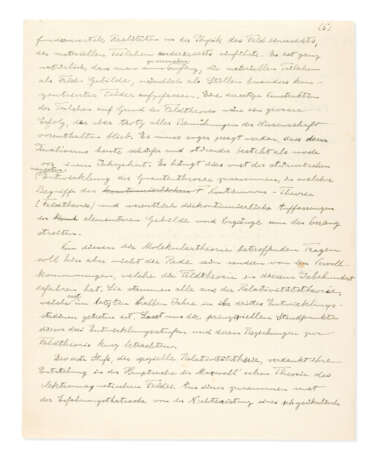

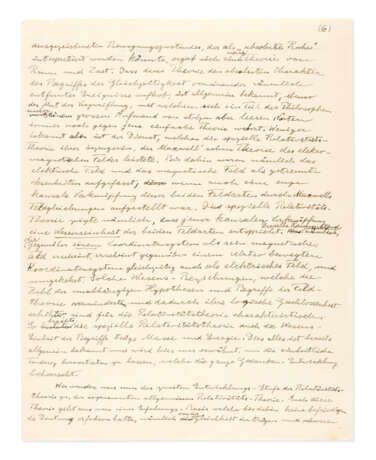

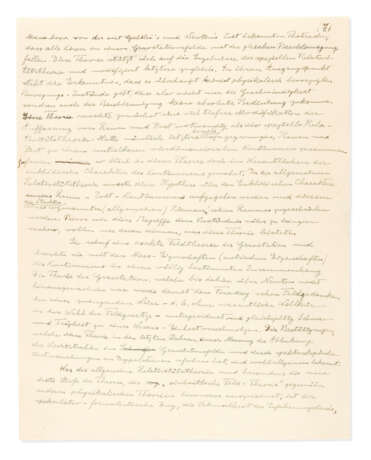

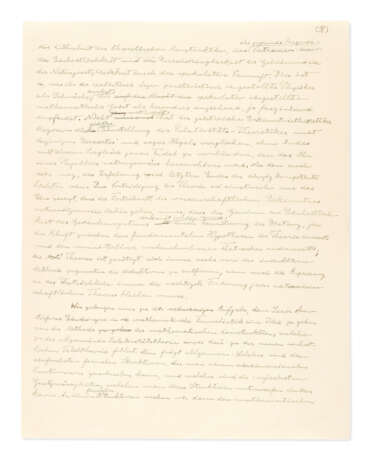

Autograph manuscript signed (‘A. Einstein‘), ‘Altes und Neues zur Feld‐Theorie‘, [Berlin, before 3 February 1929], with two pages of scientific workings. In German. 14 pages, 290 x 229mm.

'…The characteristics which essentially distinguished the general theory of relativity … from other physical theories are the degree of formal speculation, the slender empirical basis, the boldness of its theoretical construction and, finally, the fundamental reliance on the uniformity of the secrets of natural law and their accessibility to the speculative intellect …'

Einstein explains relativity. The father of 'the most beautiful physical theory ever invented' recounts the history of its discovery, explains its working, and looks to the possibility of completing the cycle of relativity in a 'unified field theory'.

Content:

Einstein begins his history of field theory with a sketch of the ‘absolute’ (i.e. pre-relativistic) physics laid down by Newton. He notes that Newtonian physics left several unanswered questions to which the theory of relativity responded: these included the lack of connection between theories of gravity and electricity, the difficulties posed by the behaviour of light, and the misleading ‘ether’ theory. He records the origins of field theory in the electrical work of Michael Faraday, and the crucial contribution of James Clerk Maxwell in bringing together electricity and magnetism in a single mathematical formulation.

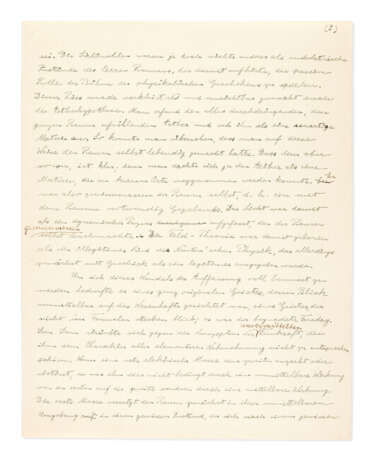

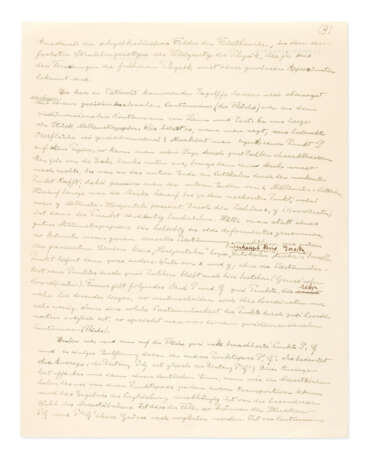

The manuscript goes on to elaborate on Einstein's own remarkable achievements in field theory. The first of these is the development of special relativity, including its discovery of mass-energy equivalence (the famous E=mc2). He then follows by recounting the birth of general relativity, beginning with its conceptual starting-point and underlining its fundamental implications for the understanding of the structure of space and time: with a rare flash of pride Einstein points to the uniqueness of the general theory, including 'the boldness of its theoretical construction', and reminds the reader of its experimental confirmation.

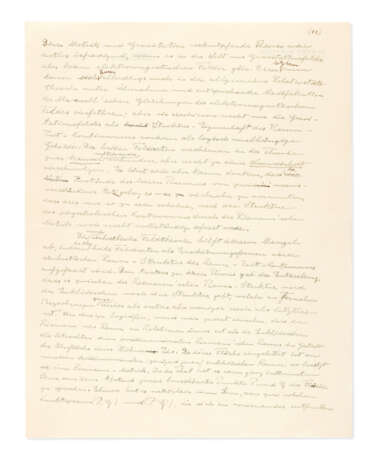

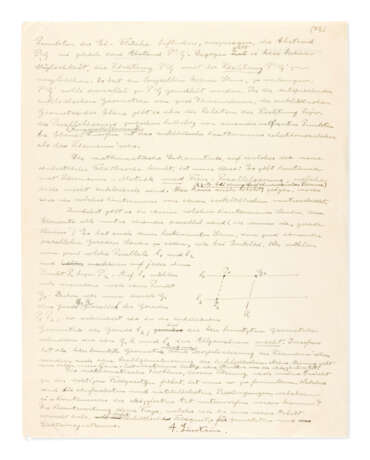

The last stage of the article sets the scene for Einstein’s work on the third stage in the development of the theory of relativity: unified field theory. He begins by clarifying the distinction between a Riemannian metric and a Euclidean metric, and notes the genesis of his current work in the ‘mathematical discovery [that] there are continua with a Riemannian metric and distant parallelism which nevertheless are not Euclidean … / The mathematical problem whose solution, in my view, leads to the correct field laws is to be formulated thus: Which are the simplest and most natural conditions to which a continuum of this kind can be subjected?’.

It is particularly appropriate that on the versos of two leaves in the manuscript (ff.4 and 5) can be found extensive scientific equations by Einstein, part of his ongoing work on unified field theory.

On the special theory of relativity (1905) and the identity of mass and energy (E=mc2):

'The first, special theory of relativity, owes its origin principally to Maxwell's theory of the electromagnetic field. From this, combined with the empirical fact that there does not exist any physically distinguishable state of motion which may be called "absolute rest" arose a new theory of space and time. It is well known that this theory discarded the absolute character of the conception of simultaneity of two spatially separated events ... The special theory also indicated the essential identity of the conceptions inertial mass and energy'.

On the general theory of relativity (1915) and its implications for the idea of space-time:

' ... the second stage in the development of the theory of relativity [is] the so-called general theory of relativity. This theory also starts from a fact of experience which till then had received no satisfactory interpretation: the equality of inertial and gravitational mass, or in other words, the fact known since the days of Galileo and Newton that all bodies fall with equal acceleration in the earth's gravitational field. The theory uses the special relativity theory as its basis and at the same time modifies it: the recognition that there is no state of motion whatever which is physically privileged – that is, that not only velocity but also acceleration are without absolute significance – forms the starting point of the theory. It then compels a much more profound modification of the conception of space and time than were involved in the special theory. For even if the special theory forced us to fuse space and time together to an invisible four-dimensional continuum, yet the Euclidean character of the continuum remained essentially intact in this theory. In the general theory of relativity, this hypothesis regarding the Euclidean character of our space-time continuum had to be abandoned and the latter given the structure of a so-called Riemannian space…

'[General relativity] furnished an exact field theory of gravitation and brought the latter into a fully determinate relationship to the metrical properties of the continuum. … Gravitation and inertia were fused into an essential entity. The confirmation which this theory has received in recent years through the measurement of the deflection of light rays in a gravitational field and spectroscopic examination of binary stars is well known'.

Context:

In the late 1920s, Einstein was by some distance the most famous scientist in the world, and arguably the most famous scientist in history – a status built above all on the twin achievements of special relativity in 1905 and general relativity in 1915, and sealed after the announcement of the experimental confirmation of general relativity in December 1919.

By early 1929, there was a widespread belief that Einstein was on the verge of putting in place the third stage of relativity by combining general relativity and Maxwell’s theory of electromagnetism into a single physical and mathematical framework, a 'unified field theory', which would account for all of the then-known fundamental forces of nature. This was prompted by Einstein's announcement of a new approach to unified field theory, initially in two brief papers in June 1928, and at greater length in his article ‘On the current position of field theory’ in the Festschrift for Aurel Stodola early in January 1929. Einstein's new field equations, published in his paper ‘On the unified field theory’ which was submitted to the Proceedings of the Prussian Academy of Sciences on 10 January 1929, excited immense public interest – the paper sold more copies than any other published by the Prussian Academy, was reprinted in English on the title page of the New York Herald Tribune (1 February) and was even (as Arthur Eddington informed Einstein with some amusement) displayed for popular consumption in the window of Selfridge’s department store in London.

It was in response to this unprecedented public interest that Einstein was persuaded to ‘explain his new work in a form as simple as the subject will allow’ (as the New York Times put it). The result is the present manuscript, which has been described as ‘a tour de force through the history of field theory’ (Tilman Sauer. ‘Field equations in teleparallel space–time: Einstein's Fernparallelismus approach toward unified field theory', Historia Mathematica 33 (2006) 399-439). Einstein’s article was published in an English translation by L.L. Whyte in a special supplement to the New York Times, 3 February 1929, under the title ‘Field Theories, Old and New’.

Any manuscripts by Einstein relating directly to special or general relativity are rare at international auction, and we are aware of only two in which he offers a non-technical explanation of relativity. The closest comparable to the present manuscript is the draft for his 1933 lecture at the University of Glasgow, 'The origin of the general theory of relativity', 8 pages, sold at Christie's New York, 22 June 2010, lot 195, for $578,500. A single-page manuscript explaining special relativity to a neighbour in Long Island in 1939 sold at Christie’s New York on 12 June 2008, lot 136, for $230,500.

Technical description:

In German. In black and (from f.7) blue ink, 14 pages on 12 leaves, 290 x 229mm, heavily corrected and revised in autograph on p.1, lightly corrected in autograph thereafter with a few editorial insertions in the hand of Helen Dukas, the text including two equations and a diagram of the structure of the spacetime continuum, plus two additional cancelled pages of autograph scientific formulae on versos of ff.4 and 5 (not in the published text); ff.1-5 on paper extracted from a notebook, ff.6-12 on paper with Einstein's printed name and address at Haberlandstrasse, Berlin, on verso.

Provenance

Presented by Einstein to his friend, the American judicial philosopher Morris Raphael Cohen (1880-1947), in March 1931 (see L.C. Rosenfield, Portrait of a Philosopher: Morris R. Cohen in Life and Letters, New York, 1962, pp. 373-375)

Charles Hamilton Galleries, New York, 21 February 1974, lot 156

Christie’s New York, 16-17 December 1983, lot 472

Collection of David Karpeles (1936-2022)

Aristophil collection, France

Artcurial, Paris, 19 November 2018, lot 753.

Literature

Diana Kormos Buchwald, Ze'ev Rosenkranz, József Illy, Daniel J. Kennefick, A. J. Kox, Dennis Lehmkuhl, Tilman Sauer, and Jennifer Nollar James (editors). Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, vol. 16 (Princeton University Press, 2021), nos 395 (‘Old and New Ideas on Field Theory’) and 396 (calculations), pp. 581-589.

| Artiste: | Albert Einstein (1879 - 1955) |

|---|---|

| Lieu d'origine: | Europe de l'Ouest, Allemagne, Europe, Suisse |

| Catégorie maison de vente aux enchères: | Lettres, documents et manuscrits, Médecine et sciences |

| Artiste: | Albert Einstein (1879 - 1955) |

|---|---|

| Lieu d'origine: | Europe de l'Ouest, Allemagne, Europe, Suisse |

| Catégorie maison de vente aux enchères: | Lettres, documents et manuscrits, Médecine et sciences |

| Adresse de l'enchère |

CHRISTIE'S 4/F, BUND ONE, No.1 Zhongshan Dong Yi Road Shanghai Hong Kong | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aperçu |

| ||||||||||||||

| Téléphone | +8602163551766 | ||||||||||||||

| Fax | +86 (0)21 6355 1767 | ||||||||||||||

| Conditions d'utilisation | Conditions d'utilisation | ||||||||||||||

| Heures d'ouverture | Heures d'ouverture

|